“I decided to go to hell and get my family out:” man returns to Sudan in the midst of war

There, in the Al-Azhari neighborhood, one of the southern districts of the capital of Khartoum, we sat a mere two kilometers from the war’s epicenter. We heard all manner of gunfire, aerial bombardments, and ground anti-aircraft weapons. At the heart of the war’s outbreak, with no means of escape, we monitored the situation via satellite.

- 2 years ago

July 12, 2024

AL-AZHARI, Sudan ꟷ On the evening of April 13, 2023, as my brother and I prepared to break our fast, my mother called. She pleaded with me not to leave Germany and travel to Sudan the following day. Despite her request and the looming threat of war, I remained determined to go to Sudan’s capital of Khartoum and rescue my family.

A mix of feelings overcame me. I felt fear for my family, a touch of denial, and a resolute determination to get them the hell out of there. The deadline set by the Sudanese Army for the Rapid Support Forces to withdraw from the Merowe Airport was about to expire and I didn’t hesitate for a second.

Nine hours after landing, man finds himself near the epicenter of the Sudanese War

I knew traveling during the outbreak of war created uncertainties. The conflict would displace people and leave them homeless. Others would flee to neighboring countries for refuge. The real possibility existed that I might not find my family.

I thought of my elderly mother, suffering from diabetes and high blood pressure. I kept my mind on her, and the hope of reuniting my family in the end. When the Sudanese army issued the two-day deadline for the Rapid Support Forces to withdraw, I knew a failure to comply would result in an attack. If RSF remained, deemed a rebel force, the Army would no doubt remove them on April 14.

That day, I headed to Frankfurt International Airport, awaiting news of war at any moment. I checked for updates moments before the plane took off down the runway. After safely landing at the Khartoum Airport in Sudan after midnight, I went home to Al-Azhari and slept. At 9:30 a.m. my mother awoke me to the sound of powerful artillery. On April 15, 2023, the war began in Sports City.

Flipping through the satellite channels on television, we witnessed the first hour of the Sudanese War and the destruction of the Khartoum International Airport. I thought, “What dreadful luck! A war erupted a mere nine hours after my arrival in Sudan.” From the outset, I could see this was not being promoted as a swift, lightning-fast war. It looked more like the start of a 10-year conflict.

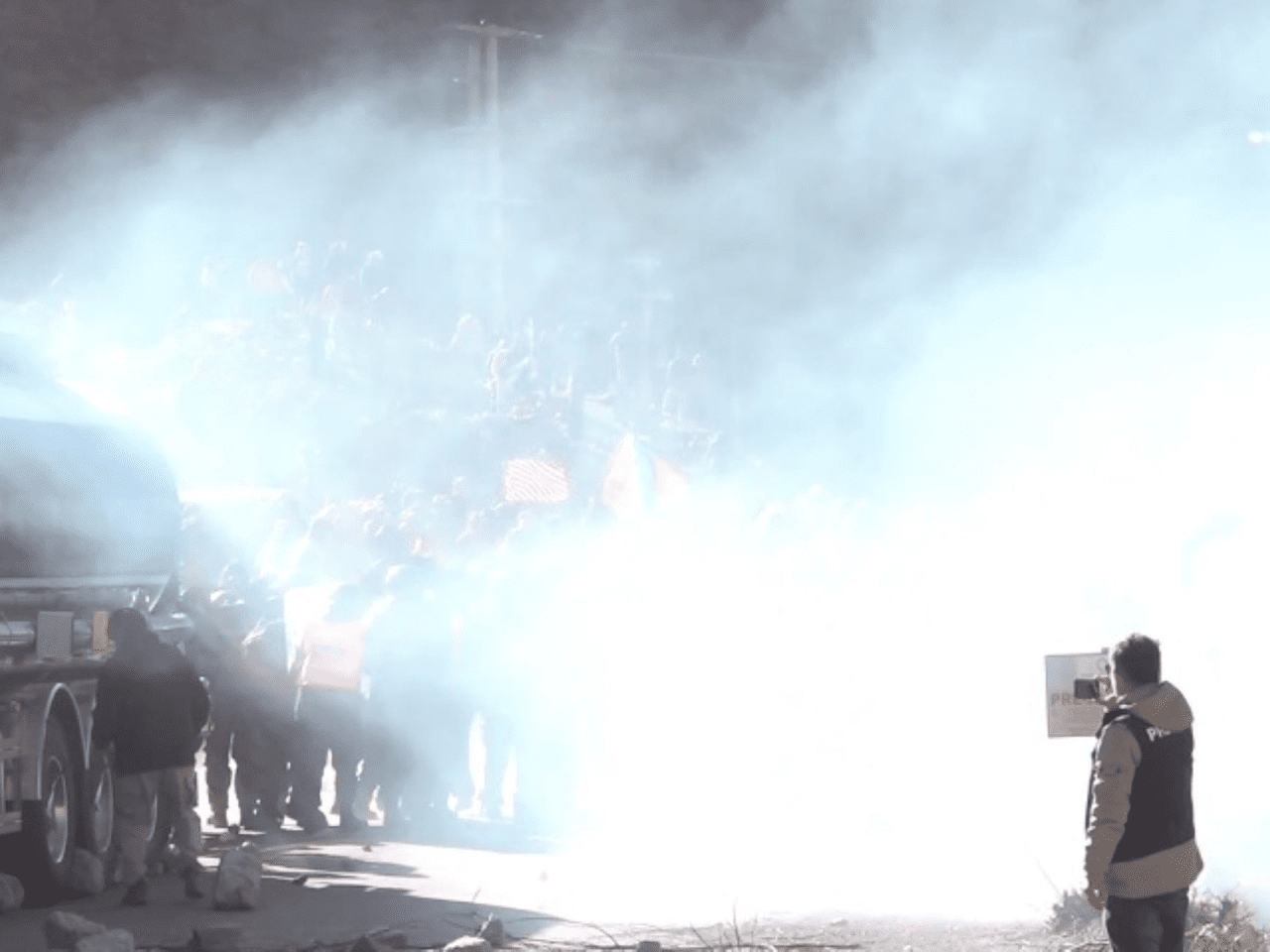

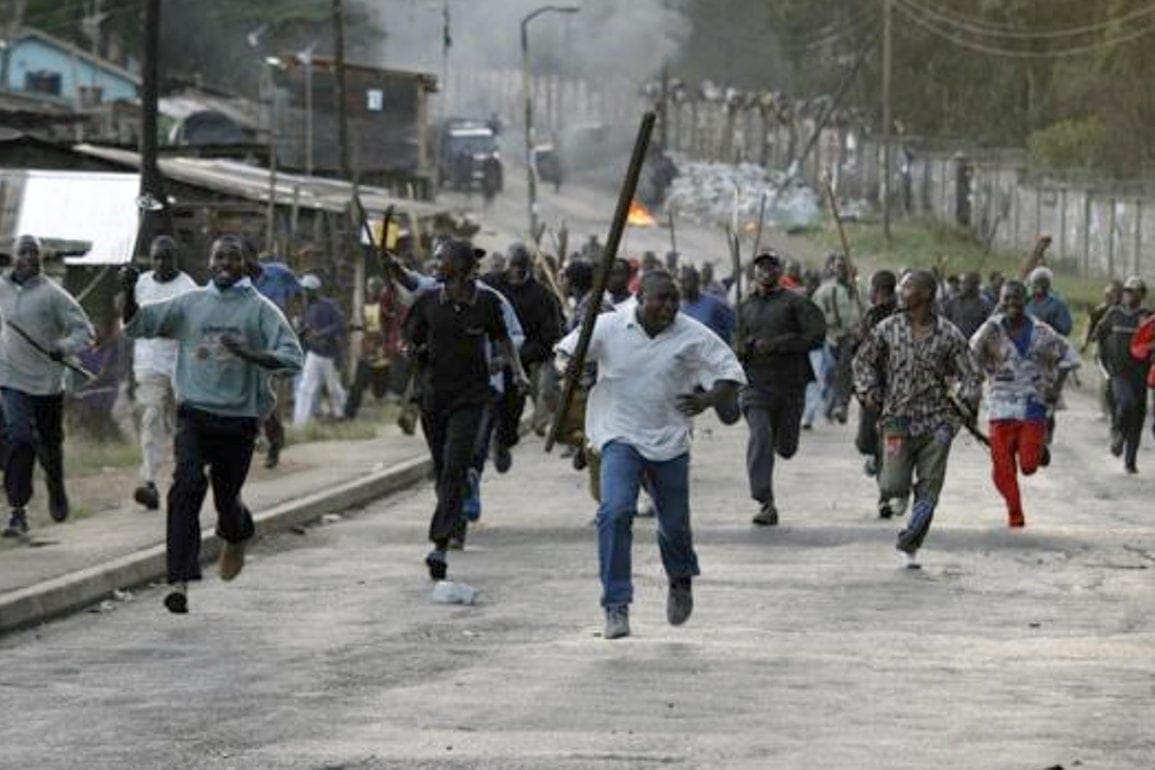

There, in the Al-Azhari neighborhood, one of the southern districts of the capital of Khartoum, we sat a mere two kilometers from the war’s epicenter. We heard all manner of gunfire, aerial bombardments, and ground anti-aircraft weapons. At the heart of the war’s outbreak, with no means of escape, we monitored the situation via satellite.

After seven days, supplies diminished and fighting loomed in

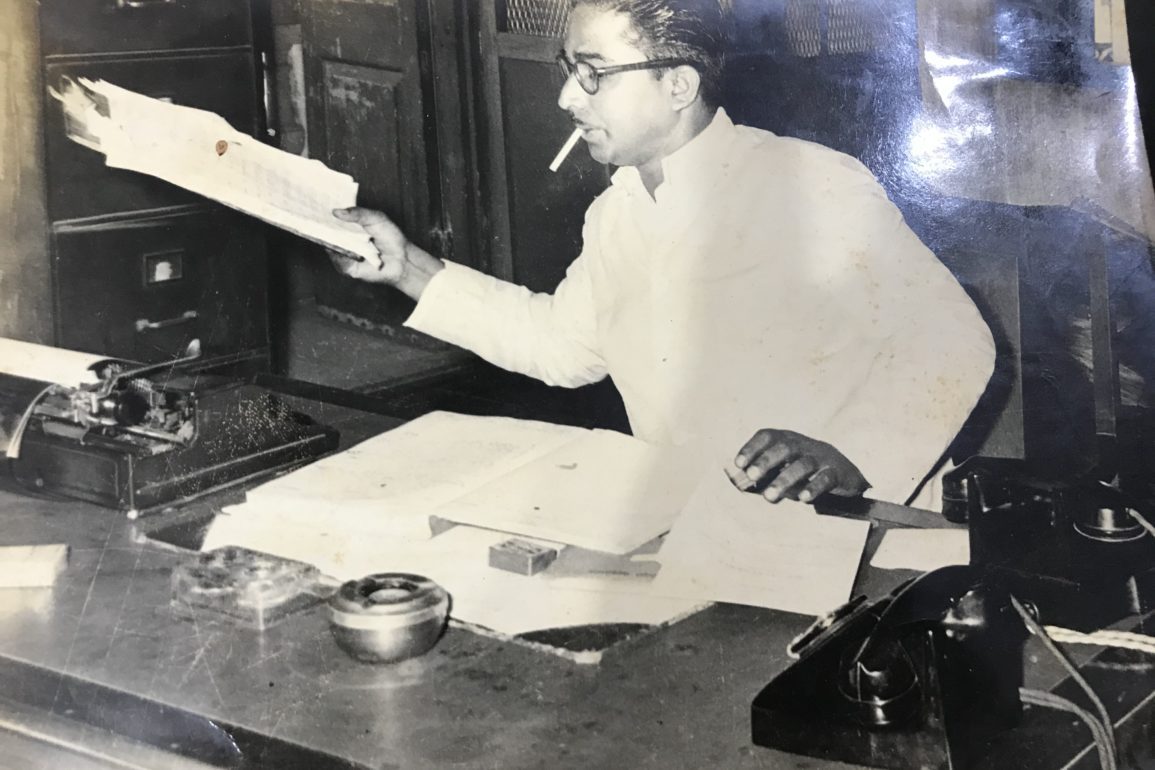

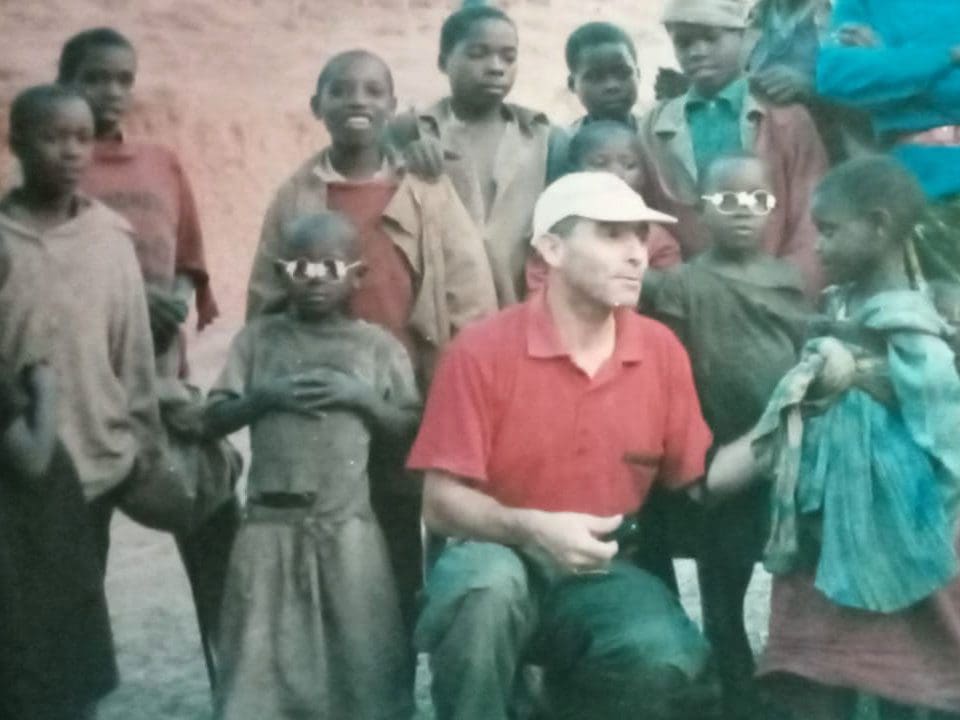

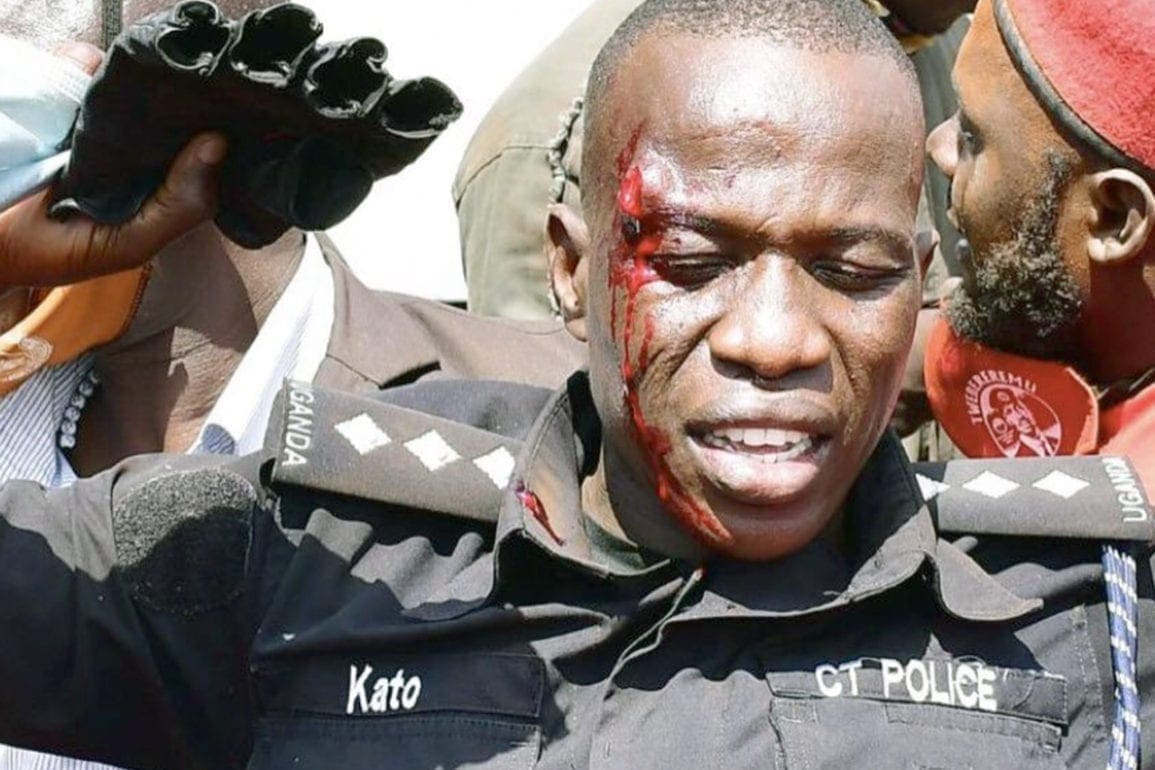

Having worked as a doctor in Darfur during years of conflict, I did not feel afraid of the war for myself. I feared for my family and my patients. Living in the shadow of media blackouts and misinformation, we faced a week of ambiguity. Each party made false allegations against the other and we could not be certain what was happening. Medicine and food became harder to come by.

In times of war, truth often becomes the first casualty. Tension between political positions arise. Propaganda and counter propaganda grow, yet civilians need truthful information to protect themselves. It becomes a difficult equation for those communicating to provide citizens what they need without destroying the morale of fighters in the field.

Throughout the war, all state institutions in Sudan disappeared. The absence of the Ministries of Interior and Information meant that no one was left to guide citizens on where to go. As a result, we sat besieged in Al-Azhari until the dawn of Eid on April 21, 2023. Throughout that week, food supplies diminished, and we struggled even to get bread. Bakeries closed a few days after the war started, and stores emptied their goods and closed. Electricity shut down and supplies quickly dwindled.

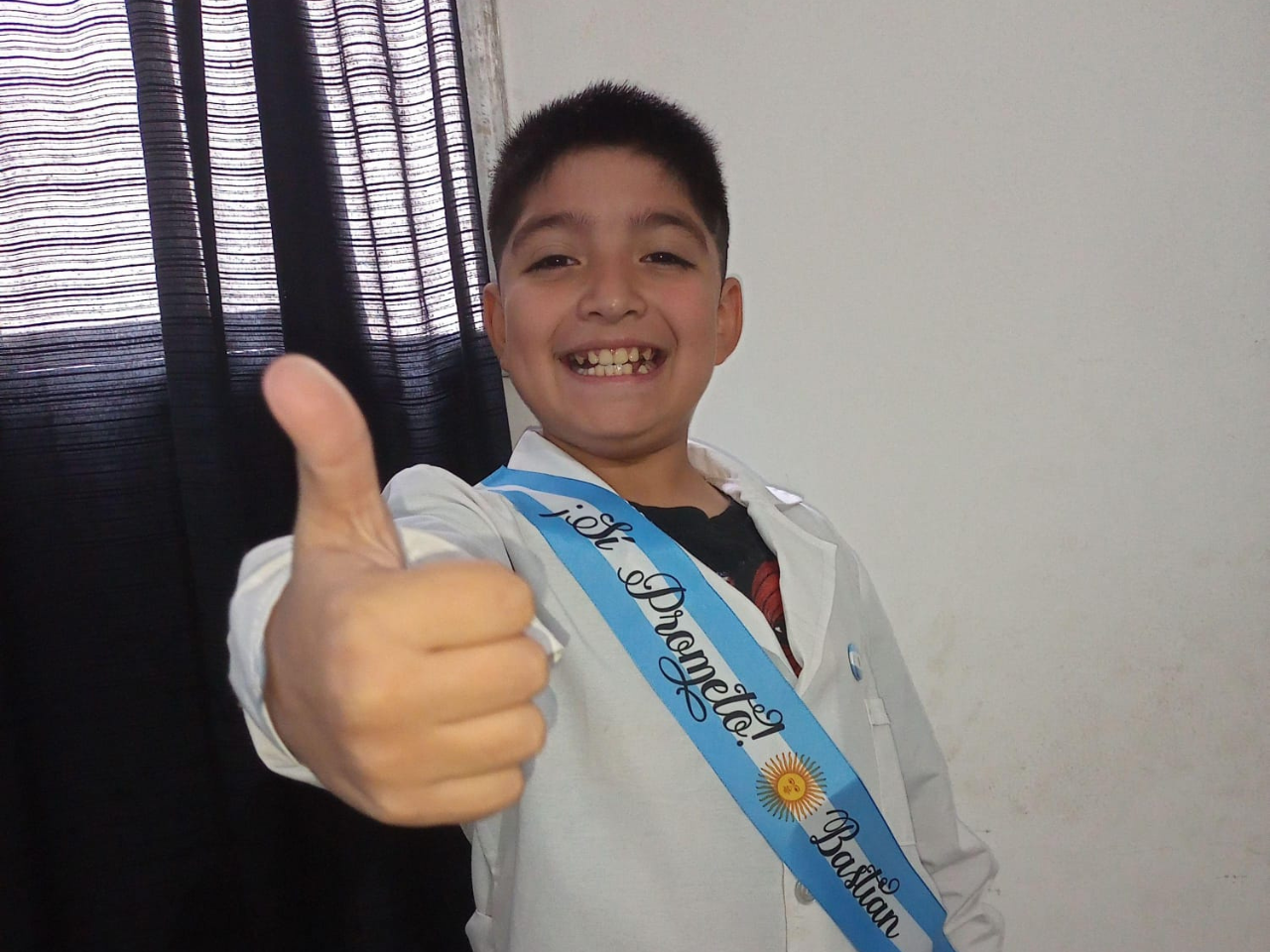

I went for three or four days with no sleep and felt on the verge of collapse. Meanwhile, my mother ran out of medicine. I feared being bombed or stormed by soldiers as clashes broke out. So, on the seventh day, we left for Aljazeera with a promise to my mother, we would one day return.

Weaving their way through war

Displaced from the hell of the war in Khartoum, we arrived in the area north of Al Jazeera, but on that very same day, it fell under the control of the Rapid Support Force. “What rotten luck,” I thought. So, again, in three days, we moved, this time to return to Al Azhari and then north to Halfa on the Egyptian border.

Twice on our return trip in an area controlled by the Mujahideen, Rapid Support soldiers searched and investigated us. Looking for weapons or army personnel, they found nothing, apologized, and sent us on own way, calling it “routine procedure.” We spent three days outside of Khartoum and I began to feel pressure. I came to Sudan on vacation. With limited time, I was supposed to return to work.

Leaving the house, this time for Egypt, we sought out what scarce information we could find. On phone calls with relatives, we asked about safe passage. Those very spots could go from safe to unsafe in the span of a half an hour. After contacting my Sudanese-British friend in Cairo, she helped me obtain the necessary information to get five seats on a bus to Egypt.

My mother prepared food for the road and gathered water. We carried only the necessary clothes and used what fuel we had left to get closer to the bus station. A relative came to take the car as we moved toward the buses. We later learned the Rapid Support Force seized that and another car we left behind without fuel.

Sudanese family moves from a burned-out city to the Egyptian border

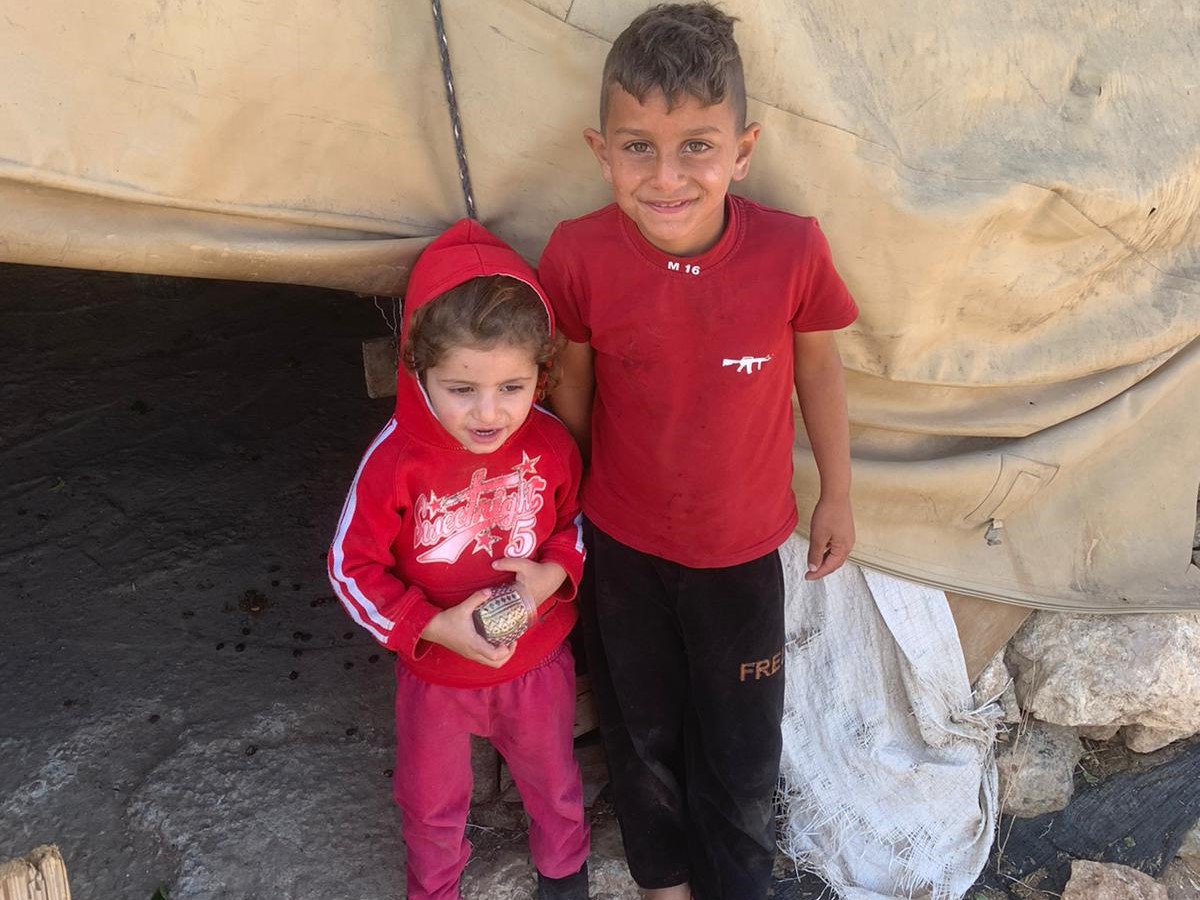

Safely on the bus, I watched as we passed through all the burned-out areas of Khartoum. Along the way, my brother, his wife, and three children boarded the bus nearer to their home. On the eleventh day of the war, Khartoum Bahri looked like a gutted ghost town, under complete control of the RSF.

The scale of devastation and destruction appeared worse than that of the Syrian War. Leaving it all behind, we breathed a sigh of relief. The five of us, along with the five people from my brother’s family, each paid $600 to escape. Arriving at the border city of Halfa, we made considerations for crossing.

As a citizen of the European Union, I had no issues. The Egyptian authorities also agreed to allow my elderly mother to pass. My male brothers, however, needed visas. With all the hotel rooms occupied, we found ourselves in a state of general chaos. Thankfully, a young man from the area hosted us. When the time passed, we decided the women and children should enter Egypt and the young men would wait.

Many buses gathered on both the Sudanese and Egyptian sides of the crossing. There we found a warm welcome and solidarity. Awaiting the ferry carrying several buses across Lake Nasser, we slept until the ferry took us to Aswan.

My eldest brother who lives in America came to Cairo to receive my mother, sister, sister-in-law, and the children. He booked them a hotel near Tahrir Square and after three days, I joined them. Because it was only the second week into the Sudanese War, we easily found a furnished apartment in Cairo and after checking in on my family, I booked my return to Germany.

The Sudanese: a forgotten people

Back in Germany, I returned to work and fell into a state of shock from the war. Yet, it also became a critical experience. I witnessed the events in Sudan firsthand, allowing me to develop an understanding of the need for the end of the fighting.

Ours became one of the first families from Sudan to leave for Egypt, and many family members and acquaintances followed suit. My uncle, who suffered from diabetes, died from lack of medicine. His children fled to Egypt after his death. Those without the financial means to leave Sudan became dispersed to parts of the country outside the scope of war.

The humanitarian conditions in Sudan remain difficult and complex. The country is paralyzed, with no source of income for families, dwindling medicine, and lack of medical services. The most important question we can ask is when will the war end; when will the suffering stop? Like Libya, Syria, and Yemen, that end seems far off.

Like the Taif Agreement in Lebanon that ended the war, we have no luxury of choosing ideal models. The people welcome any truce to stop the war, but reaching such a settlement could take years. Negotiations take place under the auspices of the Saudis and Egypt may still sponsor a settlement. It could be that the government controls certain areas, while the opposition controls others.

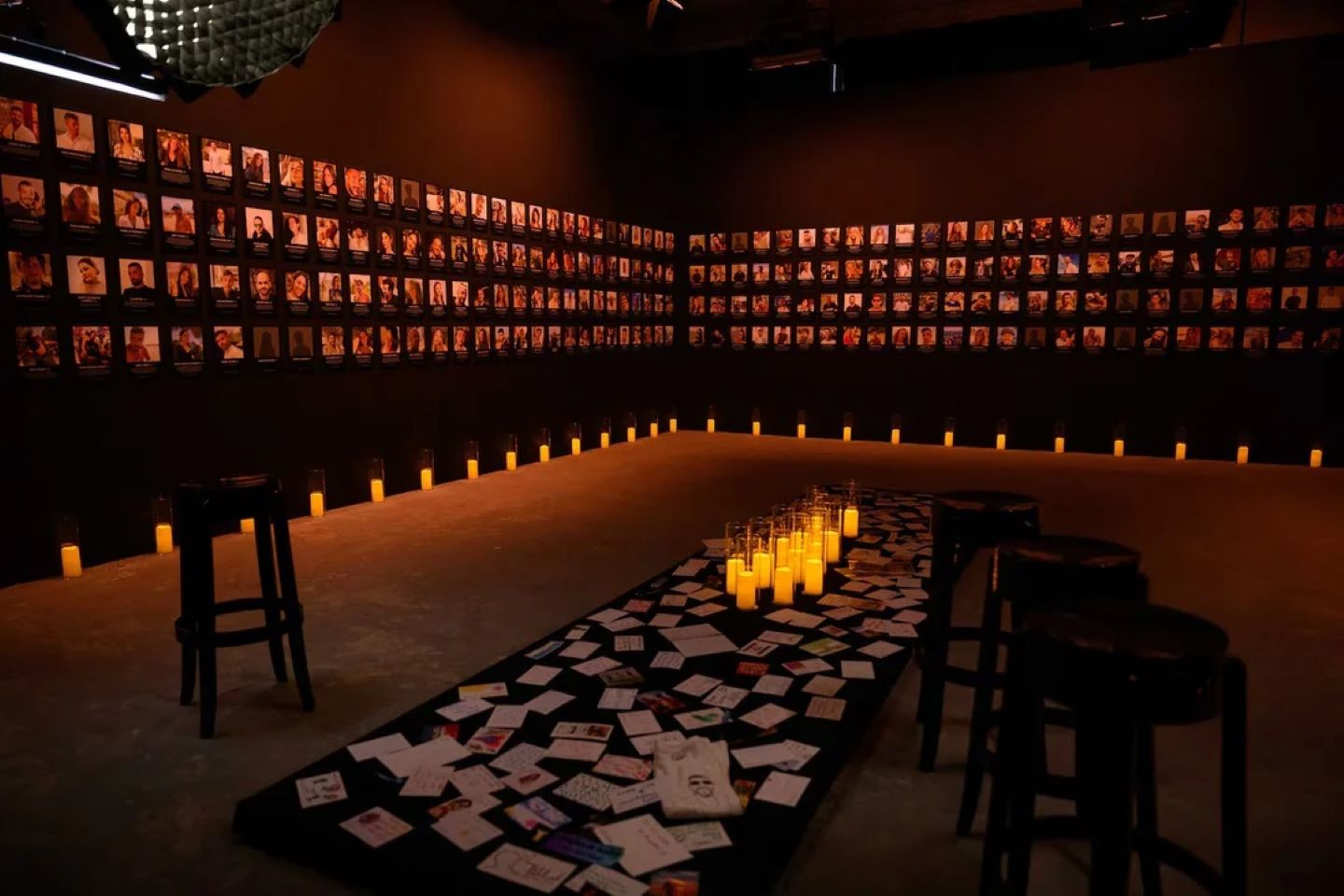

As it stands, the current conflict with its great cost to humanity respects no rules of engagement or international humanitarian law. It violates all treaties as the international community watches with seeming indifference. We feel like a forgotten people.