Cusco native develops fog catchers, bringing water and hope to Peru’s driest communities

When we arrived, the locals seemed surprised but trusted us. We set up Fog Catchers by fencing off areas with nylon mesh stretched across six-by-four-meter surfaces, supported by wooden or aluminum frames in the high hills. Soon these structures turned fog into a source of water for the community.

- 1 year ago

September 3, 2024

CUZCO, Peru — Lima in Peru is one of the driest cities in the world. It sees little rain and many of the slums sit within semi-desert areas. With around a million residents lacking access to clean water, I felt compelled to do something. I came up with a solution to install plastic nets to capture water from the fog which blankets parts of Peru.

My invention, the Fog Catcher, collects droplets of water from the air and channels them through pipes into tanks. In doing so, we provide water to marginalized communities. This life-changing resource not only brings water to people in need, but it also transforms their outlook. Watching these communities gain hope and discover opportunity brings me immense joy.

Read more environment stories at Orato World Media.

From the jungles of Cusco, man embarks on a journey of resilience and innovation

I grew up in a small house perched on a mountain at the edge of the jungle near Cusco. My parents worked as farmers, tending the land from sunrise to sunset. When my mother passed away, my siblings and I took on responsibilities to keep the household running. I started working at seven years old.

One of my responsibilities included fetching water from a spring 600 meters uphill. I enjoyed the task, despite the steep climb. I also prepared our meals, while my siblings gathered firewood and worked the fields. To reach school, we walked seven kilometers along the Yanatile River. We awoke at 4:00 a.m. and left home just before 6:00 as the sun started to rise.

After returning from school at 4:00 p.m., I changed my clothing and headed straight out to collect water again. The torrential rains in our area drenched everything at times, and our roof, made of calamine, condensed steam into water. We cleverly funneled the water using banana buds as natural gutters, collecting it in a 200-liter barrel. I began harvesting water before I learned to read or write.

Years later, I moved to Lima in search of a better life. Those early years proved difficult, and I grew up quickly. I often slept on the streets or in parks. Over time, I found work and settled in Ancon, 40 kilometers from the city.

My first home was a flimsy wooden structure that I fenced with plastic mesh to deter thieves. One night, I noticed water leaks and realized the plastic nets I used to fend off criminals captured moisture. It reminded me of the calamine roof of my childhood home. Surprisingly, this experience led me to the idea of the fog catchers.

Fog catchers become a lifeline for Lima’s water-starved slums

After that day, I realized I discovered a way to steal water from the atmosphere. I created a simple but powerful technology, which I called Atrapanieblas [Fog Catcher], capable of providing water to those most in need. Lima, the driest city in the Americas, suffers from severe water scarcity, especially in its poorest communities.

In 2002, I founded the NGO Movimiento Peruano Sin Agua to bring this solution to the most arid areas. In these areas, people lack everything: paved roads, electricity, and drinking water. Without access to clean water, residents face extreme poverty and constant health risks. They are forced to buy water from private tanker companies at exorbitant prices, often paying nearly 10 percent of their meager monthly income.

This is five times more than what residents with public water services pay in other neighborhoods, deepening the inequality and hardship for these vulnerable communities. It rarely rains in Lima, but the relatively mild temperatures and constant cloud cover create the perfect conditions for Fog Catchers to work effectively in certain areas. Villa María del Triunfo, a dry, inhospitable area south of Lima, became the ideal location for our project.

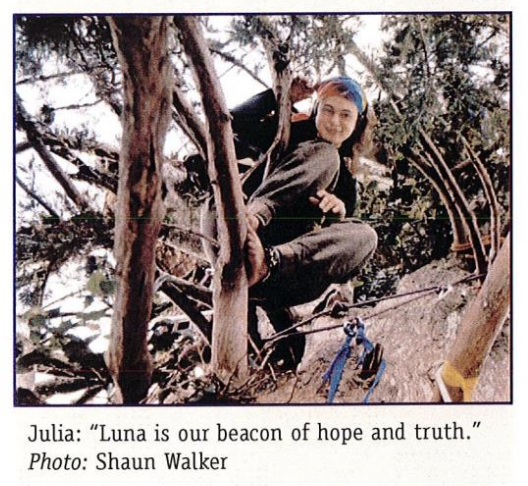

When we arrived, the locals seemed surprised but trusted us. We set up Fog Catchers by fencing off areas with nylon mesh stretched across six-by-four-meter surfaces, supported by wooden or aluminum frames in the high hills. Soon these structures turned fog into a source of water for the community.

Harnessing fog: a simple invention transformed water access in Peru

I kept the idea simple, to capture thousands of tiny droplets of water as they adhered to the mesh. I then guided them through a tube into a container. This created a system capable of delivering 200 to 400 liters of water per day, depending on cloud density. With the community eagerly watching, we installed the Fog Catchers and began monitoring the water collection.

For eight days, I measured the results each morning, but nothing happened. Despite our efforts and anticipation, the mesh remained dry during those initial days. At first, I thought the Fog Catchers failed. Then, on what I thought would be the last day, I arrived to find over 20 liters of water captured. I felt skeptical, thinking maybe a neighbor added water to trick me. To be sure, I installed five more Fog Catchers and a 100-liter container.

The next day, to my astonishment, the container overflowed with crystal-clear water. I felt a surge of energy and shouted with joy. The community joined me in celebration, thanking Pachamama [the earth], the sun, and the Apus [the spirit of the mountains]. The moment became unforgettable. One single mother, who had seven children and lived in poverty, came to me with tears of gratitude. She told me they all bathed in the same water, and this would completely transform their lives.

Another woman, around 80 years old, approached me, took my hands, and with tears in her eyes, thanked me for what she called “magic.” She could barely believe it, having lived her entire life without access to clean water.

Celebrating the magic of water: community gratitude in Peru’s arid lands

Between Moquegua and Arequipa a stretch of 90,000 hectares of vast desert and barren land often lacks a single drop of rain. We installed a network of Fog Catchers, but there was no fog, only a pristine blue sky. The community felt heartbroken, so in the quiet of dawn, I called upon the Apus, praying for fog. In less than half an hour, the mist began to roll in, thickening as it kissed the hills.

Astonished, I thanked the heavens. Water began flowing in the following days, and the community celebrated with a colorful ceremony honoring the local water saint. They gathered in the main area and began a traditional, ancestral dance of the high Andean culture of Peru. Their bodies swayed to the music, evoking the water they so desperately needed. The vibrant colors of their costumes blurred into beautiful patterns, exploding into life-like stars.

It felt as if a divine connection was made, all set against the stark beauty of the inhospitable desert. The wooden crosses supporting the fog-catching mesh became part of the scenery, framed by the green hills and the ethereal white mist. I stood mesmerized by the beauty, knowing I witnessed something sacred. That moment felt like more than magic. It felt like I was transported to another universe.

Amidst laughter and applause, the community gathered for the “Comelona.” Each family cooked and shared food at a long table, covered with brightly colored tablecloths. We stayed there until the sunset, bathing us in a warm spectrum of yellows, oranges, and reds. Beyond installing Fog Catchers, we created bio gardens that transformed lives. Our work offers hope, shifting communities from extreme poverty to sustainability. Watching gardens grow including tomatoes, lettuce, and onions, opens new opportunities for families who previously dared not dream of such possibilities.

Fog Catchers change lives in Peru

Families once surviving on just $3 a month in remote areas now dream bigger thanks to Fog Catchers that solved their water problems and opened up new opportunities. My project began small but grew to gain global recognition. So far, I installed around 6,000 Fog Catchers, to reach 10,000 in total. While the recognition means a lot, my focus shifted to making the water more drinkable.

Currently, the water collected by Fog Catchers remains suitable mostly for irrigation and cleaning. I now research natural purification methods, such as moringa seeds and rat-rat root, which the ancient Peruvians used to purify water. I am designing new Fog Catchers that adapt to wind direction and function in low rainfall conditions, maximizing the collection efforts.

My ultimate goal is to regenerate springs and lagoons that are threatened by natural cracks. We already began this work, identifying three draining lagoons in the Cusco highlands. I plan to fill these cracks with stones and install fog-catcher domes, which will act like roofed coliseums, capturing water from clouds and feeding it back into the springs.

Fog Catchers could reduce cloud density by 70 to 80 percent, potentially saving thousands of lives in areas suffering from water scarcity as climate change worsens. More than 20 years ago, I started my adventure with El Movimiento Peruano Sin Agua, widely known in Peru as Los Sin Agua.

Since then, we have worked tirelessly, installing thousands of Fog Catchers across Peru and in other countries, bringing hope to communities in need of clean water. It feels fulfilling to see my dreams realized, but with millions still lacking clean water, I will continue this work wherever it is needed.

All photos courtesy of Abel Cruz Gutiérrez Echaratino.