Family flees Belarus, years later woman launches Inheritance Project

Waves of Russian friends left Instagram and Telegram. We stepped through a door to a new reality. Russia entered the dawn of renewed oppressive authoritarianism, and my Russian friends became paranoid. I felt it.

- 4 years ago

August 12, 2022

BROOKLYN, New York ꟷ The days before the Russian invasion of Ukraine my partner and I spent a week in Lake Atitlán, Guatemala.

A 6.8 magnitude earthquake left a palpable feeling of pressure in the atmosphere. As I crawled into bed on our last night, I felt a sharp pinch on my finger. I yelped and jumped out of bed as a scorpion scooted out from underneath my pillow.

Airport brings back memories of early immigration

At 1 o’clock in the morning, with no hospital nearby and transportation mostly by boat, I entered a state of shock. As an immigrant, I was born into chaotic life or death situations, so my version of shock equated to full, clear planning mode.

I put on my clothes and shoes in case I became paralyzed, as my partner and I intensely researched the scorpions around the lake. We discovered their bite was not lethal. Spiritually and emotionally triggered by the event, I did not sleep well.

On our Red-Eye flight home, I felt restless, vulnerable, and physically exhausted. We entered customs at JFK Airport and something unusual happened. They grouped citizens and non-citizens together in one line. Families huddled while children cried. Bags lay everywhere. We could not use our cellphones. With ten television screens playing the same channel, we had no autonomy over our attention.

I wondered, who in this line is immigrating? Who is the little me, in the hands of her mother? When we came to America, my parents fit their entire lives into what they could carry on a plane. Surrounded by our carts and bags, my parents wore contraband hand-me-down jeans they acquired as teens in Russia, while I sat in a little cart that said, “Welcome to New York.”

I don’t have conscious memory of my immigration to the United States at a year and a month old, but my body remembers.

Fear builds at the border of Belarus

We flew from the former Soviet Union and arrived at JFK airport. The sensation of fleeing with my parents carried through my first years of life in New Jersey. I often felt disoriented, overwhelmed, and nothing made sense. Airports felt like a machine, full of dehumanizing beings.

I was told, as a child, I did not listen to authority; I peed on the plane. Because we had papers proving a special refugee class, we moved to a separate holding area at the airport. Officials instructed everyone to form a line, but I kept running around. The others waited for my mom to control me. Eventually, they ushered us into a room where they lectured us on how to be American.

Now, here I was again as an adult, still processing the scorpion bite from the night before, while reliving this airport experience. My mind circled back to the pervading question, “What do I want to do with my life before my time is done?” Just then, some military general on the news announced Putin was sending more troops to the border of Belarus. Fear was building steadily around a potential invasion of Ukraine.

I suddenly realized I missed a new development during my weeks’ vacation. Belarus – the country where I was born – became a lynchpin for the invasion. My eyes darted from television screen to television screen as the airport worker stopped everyone and said, “Who has a U.S. passport?”

My partner and I responded in the affirmative, while my mind drifted back to me, as a child, waiting in line with nothing but refugee papers. In a moment of extreme privilege, the worker pulled us out of line and sent us to another kiosk.

Bombs fall on Ukraine, frightened Russians and Ukrainians connect

Back in my apartment, exhausted and hungry, I wanted comfort food. I picked up a bacon, egg, and cheese bagel – something so American you’d never find it in Guatemala. At nearly the exact moment I devoured the sandwich, real-time footage showed images of the war breaking out in Ukraine. I became violently ill.

For the next six hours, I threw up in my toilet in Brooklyn while bombs landed all over Ukraine. Russian friends called to try and find out what was happening. Ukrainian friends called my Russian friends, and my mom called me. I felt myself go numb.

In the ensuing hours, I watched as my contacts on Instagram and Telegram shared videos of the first rockets striking. I furiously scrolled through the real news from Russia and Belarus on decentralized telegram channels to make sense of what was happening. The subsequent details remain fuzzy in my mind.

Eventually, the throwing up subsided, but I knew my body could not rest until I did something. I video chatted with a friend in Russia. He told me the night before, Putin and senior leaders appeared on the news. They claimed there would be no invasion of Ukraine. They lied.

“No one is going to support this,” my friend asserted, “This is crazy.” He said it felt like Putin dropped a bomb on all their futures, all their dreams, and everything they worked for their entire lives. People are out on the streets, he told me. The banks are shutting down and people are taking all their money out. I’m scared, but we’ll survive.

He said he had a friend fleeing Ukraine and asked me to talk to her. “Do whatever you need to, to stop this,” he pleaded. I wondered, what can I do that will make a difference?

Russia claims fake news, woman reacts to the dawn of the New Cold War

I normally would not go live to talk about issues on my Instagram, but I did that day. I interviewed friends in Russia and translated their responses.

The media machine in Russia aggressively promoted one narrative: they were fighting Nazis, and videos and calls shared by individual victims on social platforms were created by western media using deep-fake technology. Sadly, intelligent people believed them. Perhaps that was easier than facing the despair, shame, and fear of what was really going on.

Rather quickly, friends in Ukraine reported their own mothers in Russia did not believe them. As people died and beautiful cities with thriving economies reduced to rubble, I wondered, what hope do we have?

I could speak Russian, so I doubled down on telling true stories. One evening, mom and I found ourselves in a Facebook video chat with her friend in Ukraine as she hid in a bomb shelter. This is war in the 21st century, I thought.

She suggested we create a system for Ukrainians after they escape, like an Airbnb for refugees. Mom and I immediately went to work. We found an existing grassroots initiative using technology to connect refugees to people and places they could stay.

It felt like a different kind of activism – a humanitarian effort. I ceased wanting to hear anyone’s thoughts or perceptions of the war. I simply wanted to know, do you have resources or not? We’ve since made lifelong friends and supported fundraising efforts in our communities.

I always knew my unique inheritance was preparing me for something. I thought it would be something happier, but my experience prepared me for this crisis – for the dawn of a new version of the Cold War.

Russian friends begin to fear for their safety

The end of the Cold War proved an illusion. Lying in wait – invisible to the populace – it morphed the day the bombs dropped. Now it shows its face, on the news, in clear view.

Waves of Russian friends left Instagram and Telegram. We stepped through a door to a new reality. Russia entered the dawn of renewed oppressive authoritarianism, and my Russian friends became paranoid. I felt it.

We stopped having authentic conversations. I knew their apprehension sprung from questions. What can I share? Who can I trust? Who might be watching? This type of paranoia does something to people’s physiology. Empathy surged in me. After all, I entered the world with that same feeling. My mind rewound to 2018 and my last visit to Belarus, my ancestral home.

We landed in Minsk after being awake for over 36 hours – my mother, father, grandmother, and I. My mom’s friends drove us from the airport to our apartment. Along the way, mother transformed into her younger self, her heart pounding as she rattled off scenes.

“Oh, that’s the Ferris wheel where your father proposed to me, and that is the underpass where he proposed jokingly on the third day we knew each other.”

“That’s the Polytechnic Institute and Academy we all graduated from.” The school has been renamed three times since then.

Needless to say, back at the apartment, I slept like a rock until morning, when I awoke in anxious fits, until I found comfort in lying still. After several days in Belarus, my brain entered a kind of memory speed dial. With each new detail about my parents’ lives, I opened my eyes. I filled in the blanks, imagined slots, and fabricated history I placed into the puzzle of my life, so it would feel less bare.

A stark contrast between those who made to America, and those who stayed behind

At our first family dinner, we walked into a scene straight out of the soviet era movies I watched in my early days in America. A huge table stretched long, covered in Russian food. My father’s family stood in a V-shape, each with a drink in their hand.

Dad stood in the middle. In America, he had his teeth redone. There he stood, with this shining American smile. His family – who he had not seen in 25 years – asked questions. I swear, they looked straight into his mouth.

I imagined the Russian immigrant version of The Last Supper starring my father – the return of the prodigal son. The entire experience felt out of body as I documented everything. I clearly saw the invisible grief of migration – of my parents fleeing the collapse of the Soviet Union and leaving my father’s family behind.

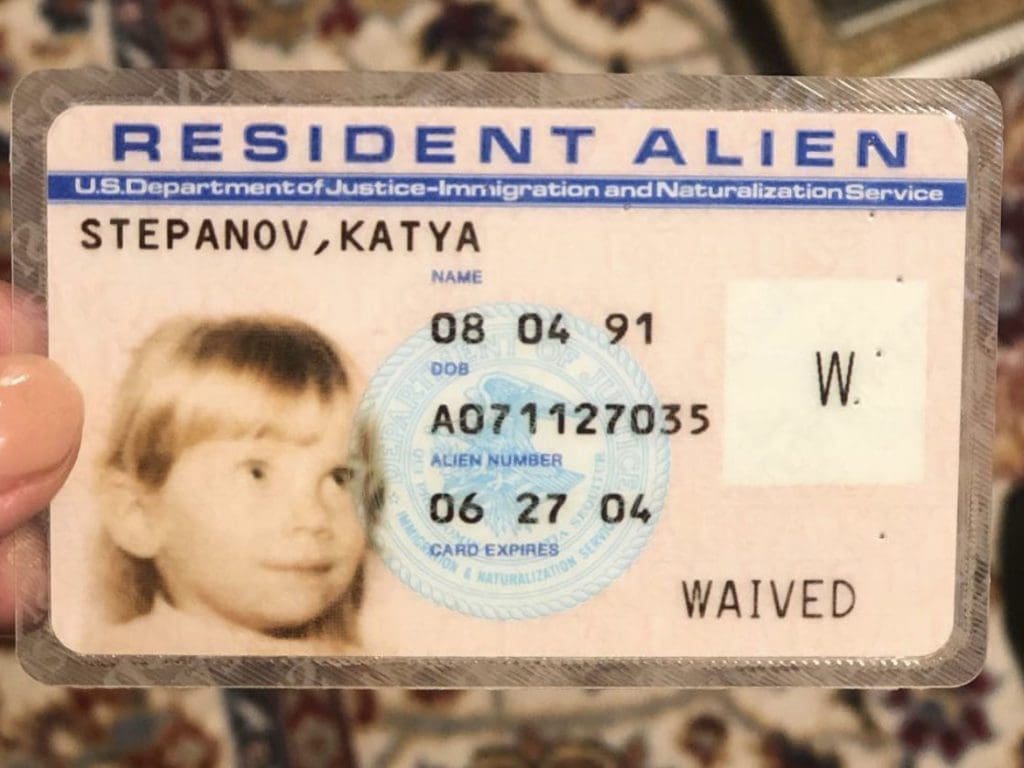

I saw my own invisible trauma and wondered, did his family feel betrayed? My mother, being Jewish, obtained special papers within a few months for us to flee. My father’s family had no such route. His brother waited 13 years to get a green card. Now, here we were, smiling and telling stories.

I watched them all – people who held me in their arms as a baby. I could not remember them. A joy I never witnessed before emanated from my father. My parents looked 20 years younger than their family of the same age in Belarus.

The privilege of being American shone through – less stress, access to healthcare and food resources, autonomy over your own life, and the ability to manifest your dreams.

Watching the news now as Ukrainian families are ripped apart and the citizens of Belarus remain oppressed by Russia, I can see, there is no right way to be in war.

Refugee helps audience understand immigration through immersive theater

The trip to Belarus gave me a newfound respect for my parents’ courage. I began to form a vision for the Inheritance Project.

I wanted to create a process for people to visit these painful places in themselves. An immersive theater maker, I decided to create a show unlike any other.

I applied for a grant through COJECO and transformed a four-room basement on Canal Street in New York City into an immersive theater experience. Audiences of 25 people at a time would interact with my real mother, grandmother, and me.

The theater had four rooms, which opened to one other in unique ways, like Alice in Wonderland. One had a closet that opened into a library. The library had a spinning wall. A labyrinth returned you to the main space. It seemed perfect for an avante garde museum of identity, I would build from my own life.

An ensemble of actors told the story with us, playing many characters throughout the show. The playbill became your Russian passport. In the Soviet era you had to specify your nationality and ethnicity – like Belarusian and Jewish. They used it to discriminate you.

At the door, with passport in hand, an American authority waited. One at a time, he scanned the passports of audience members, hazing them with questions just to get inside.

Held in the staircase in the first scene, surrounded by portraits of ancestors, a conductor’s voice rang out earnestly. “You are about to embark on the journey to the museum of identity. We’re going to jump across time. Things won’t make sense. Don’t be alarmed. This is the nature of memory.”

Participants surrendered their shoes in place of slippers and stepped into an authentic recreation of my grandmother’s apartment on her birthday.

The Inheritance Project is born

My mother greeted the guests, handing out borscht dumplings made by my childhood friend for each performance. Real photo albums mingled with vodka and candy. They crossed the threshold into a cultural home.

My grandmother entered and sat down with me. She read from a book of sayings and phrases she created in real life, as I translated to English.

Room by room, attendees experienced a constant feeling of immigration. In the white room, projection mapping portrayed a new life in America – a clean slate. I could have changed my name; could have become Kate Step, but I did not. I remained Katya Stepanov – choices that do not exist for people in the Soviet Union.

In the library, my best friend Boris gave a five-minute monologue on the history of Judaism. Later, the audience returned to the interrogation room. Forced to line up in different ways, they were peppered with questions about America.

We closed with my grandmother, giving thanks in Russian, and they left – no curtain call, no applause. They were put in and spat out in a disorienting whirlwind mirroring my own experience navigating identity. Three hundred people said, after the show, they wanted to unpack their own inheritance.

I realized the more specifically I told my story, the more revelations people had about their own identity. The personal became the universal. Three years later, The Inheritance Project is my full-time job. I facilitate leadership and inclusion workshops with organizations, guiding conversations about identity, class, country, culture, creed, and color.

We want to believe we can have unfacilitated conversations with people who are drastically different from us. Too often, however, it does more harm than good. People struggle to connect, and when they are rejected, scared, or have a nervous system response, they never try again.

As Ukrainians and oppressed Russians suffer, we must speak

At the Inheritance Project, we set people up to have those conversations through smaller, guided experiences where deep connection and understanding becomes accessible.

Looking back at my show, my trip to Guatemala and Belarus, and the emergence of the Russian war on Ukraine, I believe more than ever we must explore the parts of us that are painful; the parts that remain invisible or we want to hide.

Having conversations about those parts with others is how we collectively heal. We should never feel ashamed to look back. In our histories, we all have oppressors and oppressed. We have much more in common than we think we do.

I flash back to my trip to Guatemala, a week before Russia invaded Ukraine. Twenty indigenous tribes lived around the lake – human beings whose histories include murder, destruction, and colonization by the Spanish. Many still speak their ancestral tongue.

Today, I can appreciate the Russian culture I grew up in, while acknowledging Russia as an imperialist colonizer. I have no delusions about my culture as I engage in a radical shift to decolonize my mind.

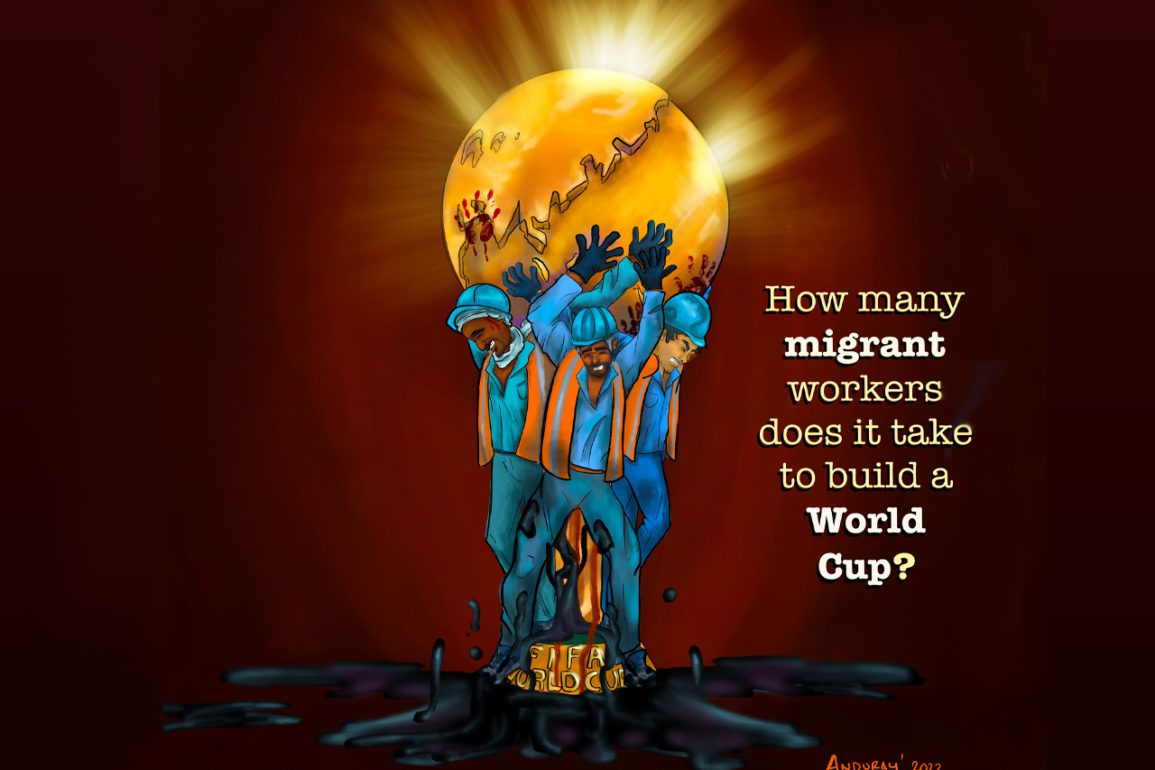

The indigenous fight in Guatemala is connected to the fight in Ukraine. It is connected to the indigenous tribes in North America fighting the oil pipeline, and our collective fight against the oil giant Russia.

Like the volcanoes in Guatemala, sometimes we feel an eruption coming, akin to the buildup of war. Keeping us separated, silent, and in fear is how authoritarianism wins.

If you never see anything outside your own country and the cities you live in, what are you going to believe? For decades, my grandmother watched Channel One in America. It served as a singular connection to her old life. She never assimilated to American culture; never learned English. She often believed the Russian propaganda.

Now they’ve taken Channel One off the air in America, and all the babushkas have lost their cultural connection, but gained something in its place. My grandmother started watching news and shows on YouTube instead. She went through an awakening – a complete 180 on her perspective. If she lived in Belarus, she would not have this opportunity.

So, I encourage you to learn your inheritance; to tell your stories; and listen to others. In some places, like Russia, if they speak, they can lose everything. We must speak because we can. To learn and share our stories, is to honor them.