Black Girls Surf fighting for inclusivity

The international organization started by surfer Rhonda Harper seeks to empower women of color in the predominantly white sport.

- 5 years ago

December 22, 2020

I live on the water and wouldn’t change it for a thing.

When I am riding atop the waves, I am in a different dimension. A sense of calm takes over and raises my spirits. It’s something that every surfer understands, yet others never will: Surfing changes you; it changes your soul, spirit, and outlook on life.

Surfing has been my life for more than four decades, but I never went professional. I never had sports role models who looked like me or even peers with whom I could relate.

That’s the life of a black woman who surfs. It was true when I was seven, and it’s true now when I’m 52. But it won’t be true for long.

We’re changing the mainstream image of a surfer one season at a time.

Catalyst to a revolution

I don’t surf as much as I once did. Now, my focus is handing over the baton as a mentor and instructor to girls of color.

As a surfer in Hawaii and Santa Cruz in the ’80s, I can still see the white-washed imagery painted by the media, advertisers, and event sponsors. Black people were never shown in the surf world.

Years later, this imagery remains unchanged in the mainstream commercialized surf industry. It’s always gnawing at my heart.

In 2006, I put up a plaque of a black-American Latina surfer on a Santa Monica beach that attracted attention from major players in the surf world. Because of this, the managing editor of Active Sports reached out to me to be part of their reporting team. As an insider, I could see the inequality and segregation that black athletes experienced.

I became a subtle activist. I sought to mentor and expose the next generation of surfing black women and envisioned a bridge over the representational gap in the sport. That’s where Black Girls Surf came into existence.

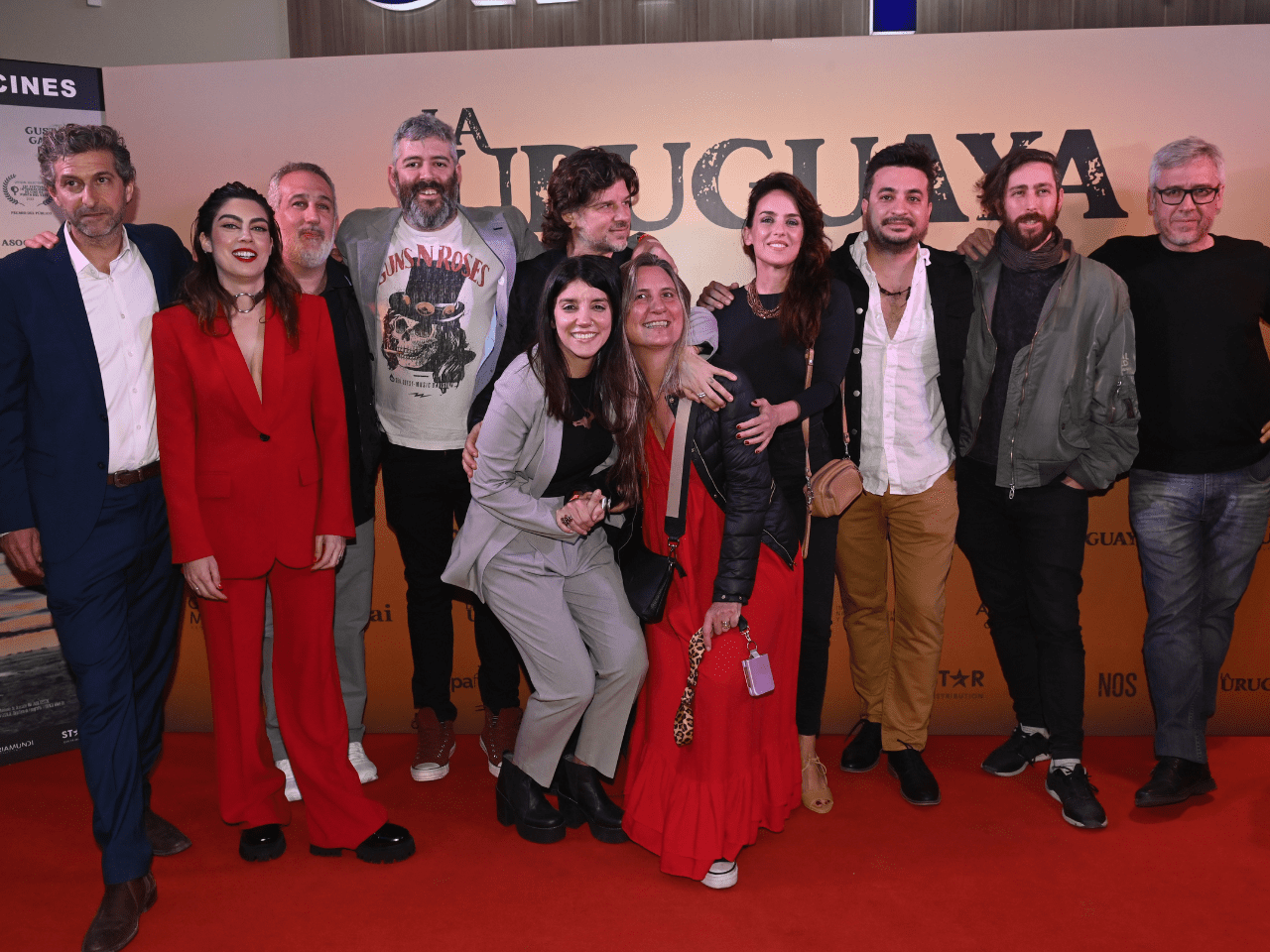

What I didn’t anticipate is the exponential growth and attention Black Girls Surf garnered from the media and industry giants.

Black Girls Surf stamped my authority in the surfing world. I had a front-row seat at the table attending surfing events and competitions both as a judge and participant as I continued championing for inclusivity in the sport.

Colored girls need representation

Black Girls Surf became a force to reckon with in the United States as awareness grew.

I felt the need to expand the campaign outside of the U.S. and established the African Surf Contest. Set to be held in Sierra Leone in 2014, I flew to Africa in 2013 to scout.

That is where I met a local surfer by the name of Kadiatu Kamara, and eventually, a surf instructor in Senegal named Khadjou Sambe.

I was happy. We had our team.

But before we could hold the event, Ebola ravaged West Africa. We had to cancel. Just like that, Kamara and Khadjou became the first members of the Black girls surf Africa chapter. They are the epitome of resilience and preparation meeting opportunity.

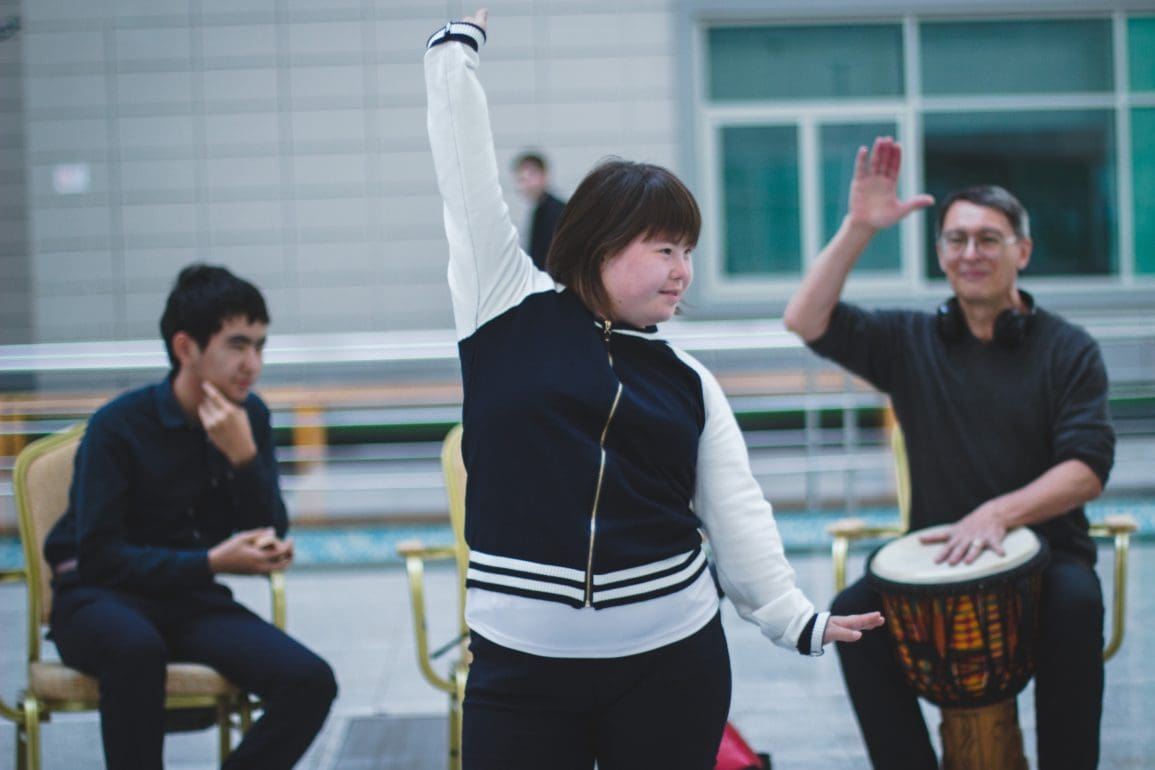

Khadjou came to California for exposure and training. The image of a young black woman riding the waves on the Californian shores, with skills as good or even better when compared to her white counterparts, made waves in the surf industry.

We had back to back interviews with the media and it was surreal. This is the type of exposure we needed. This is the moment that stays with me when I go to bed at night. It makes me so proud to be the initiator of this revolution.

Khadjou faces the same challenges of racism and bullying that I faced so many years back. It disheartens me that the surf industry remains unchanged to this day.

Fighting for representation

Seven of our girls of color will participate in the Olympic trials in 2024. It is an achievement for colored girls across the world that spent their life fighting for inclusivity.

The biggest impediment to the Black Girls Surf initiative is funding. Equipment is expensive, with a good surfing board going for an average of $600. We depend on donations of equipment from individuals and companies, which I then load onto a crate and ship to the surfing camp in Africa.

At this point, we have two camps with plans to open five more. We are also in the process of building a West African boarding academy that will double as an education center and surf academy.

My parents raised me to believe I can be anything I wanted. Black girls from Africa need to know they can be anything they want.