Missouri man sentenced to 241 years at the age of 16, new law in his name supports youthful offenders

I went through all the stages of rage behind those prison walls and held onto significant negativity. It took me three long years to stop pining and accept what happened. So much time had already passed, and yet, I knew there was no end in sight. I felt completely demoralized and alone. Eventually, I decided to turn my life around and channel my energy into bettering myself.

- 3 years ago

May 29, 2023

ST. LOUIS, United States — The day I got arrested in 1995 was like any other day. At 16 years old, I often engaged in stealing and other petty crimes around St. Louis. This time, I got caught. Being young, I never fully processed the gravity of the situation at that time. In court, the jury found me guilty.

When the judge handed down her sentence, she told me I would die in prison and sentenced me to 241 years. I would be 112 years old before I ever became eligible for parole. I went into complete shock and a numbness settled in as I started around the room.

Read more prison related stories at Orato World Media

The day they took away freedom, something ignited in me

I went through all the stages of rage behind those prison walls and held onto significant negativity. It took me three long years to stop pining and accept what happened. So much time had already passed, and yet, I knew there was no end in sight. I felt completely demoralized and alone.

Eventually, I decided to turn my life around and channel my energy into bettering myself. I turned from my negativity and began cultivating optimism, maintaining certainty I might be released one day. I began connecting with my spiritual side. When I converted to Islam, it connected me with something deeper and to develop clarity. It also helped me stay out of trouble in prison. One day at a time, my transformation began to take place.

In prison, I took up reading and enrolled in school. I began writing, completed my GED, and earned my high school diploma. With everything seemingly falling into place, my motivation to become my best self, soared, so I kept going. When I started a book club in prison, it inspired the librarians. We wrote a letter to the St. Louis County Libarary and they began creating projects to improve literacy. I earned my associate’s degree and am currently pursuing my bachelor’s.

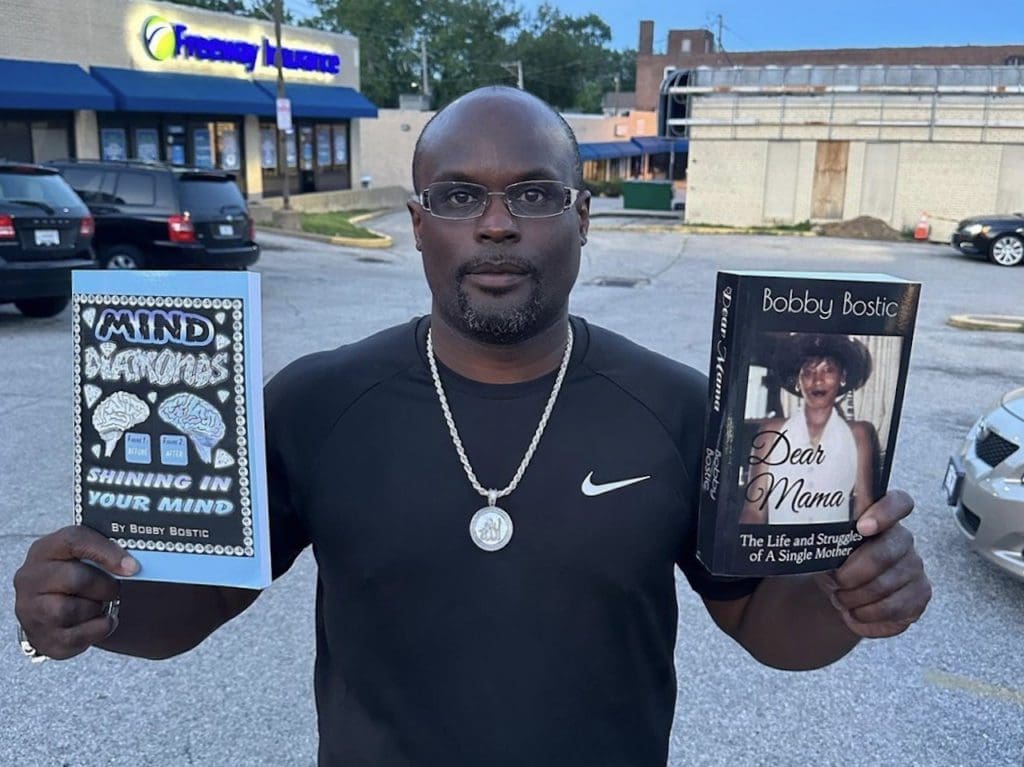

Prison offered me an opportunity to reflect, and I took advantage of it. I have written 15 books to date. One of them, titled Dear Mama, honors my mother who passed away while I was incarcerated.

His namesake became a law to help youthful offenders, judge who convicted him supports his release

In 2017, over 20 years after my imprisonment, lawmakers took notice of my case. Word got out about the details of my incarceration and public outcry ensued. It set in motion a series of events. In 2021, I learned the Missouri legislature authorized a new hearing in my case. Eventually, that led to the enactment of the Bobby Bostic Law, in my name.

The law states that incarcerated juveniles should be considered for parole after 15 years and be eligible to apply for parole every three years thereafter. During this journey, the judge who sentenced me 27 years ago became my most ardent advocate. It felt incredible to be seen for who I became, rather than the person I used to be. In November 2022, I finally became a free man.

After being in isolation for so long, I could barely believe I was finally getting out; or that the judge who sentenced me took part, years later. Upon seeing her, we embraced, and our emotions ran high. Several months down the line, I still consider my release to be a miracle.

Going back home felt strange and surreal

The day I heard the news, I stood there, with a thousand questions running through my mind. I imagined all the possibilities for my new life: the things I could do, the places I would see, and the people I could talk to again. Since being back home in St. Louis, a lot changed for me. I find beauty in everything now. The evolution of technology surprised me. I saw people who appeared to be talking to themselves and found it strange, only to notice they were speaking on their cell phones.

I also started exploring the area where I grew up again, including the rivers and waterfalls. It feels surreal simply to see people walking about and events unfolding around me. Two of the things I craved most in prison were veggie burgers and fries. To think I could finally eat anything I wanted felt amazing. I learned not to take anything for granted; to embrace every little thing.

As it currently stands, I may be on parole for the rest of my life. Yet, I feel so grateful to be free. Since my release, I collaborate with schools, juvenile detention centers, and prison departments to motivate and educate the next generation. A lot of people helped me realize my goals while I was incarcerated, so it is my time to give back to society. I want to be a voice for young people going down the wrong path and help them realize there is more to life. Most of all, I want to continue to be the best possible version of myself.