Killer whale in captivity: activists say he will die in agony if authorities fail to set him free

The first sight of him felt gut-wrenching. You could see the bones in his ribs and skull. His dorsal fin drooped, while a large bulge protruded behind his head. As I watched in shock, I felt my chest tighten and I lost my breath.

- 2 years ago

May 11, 2024

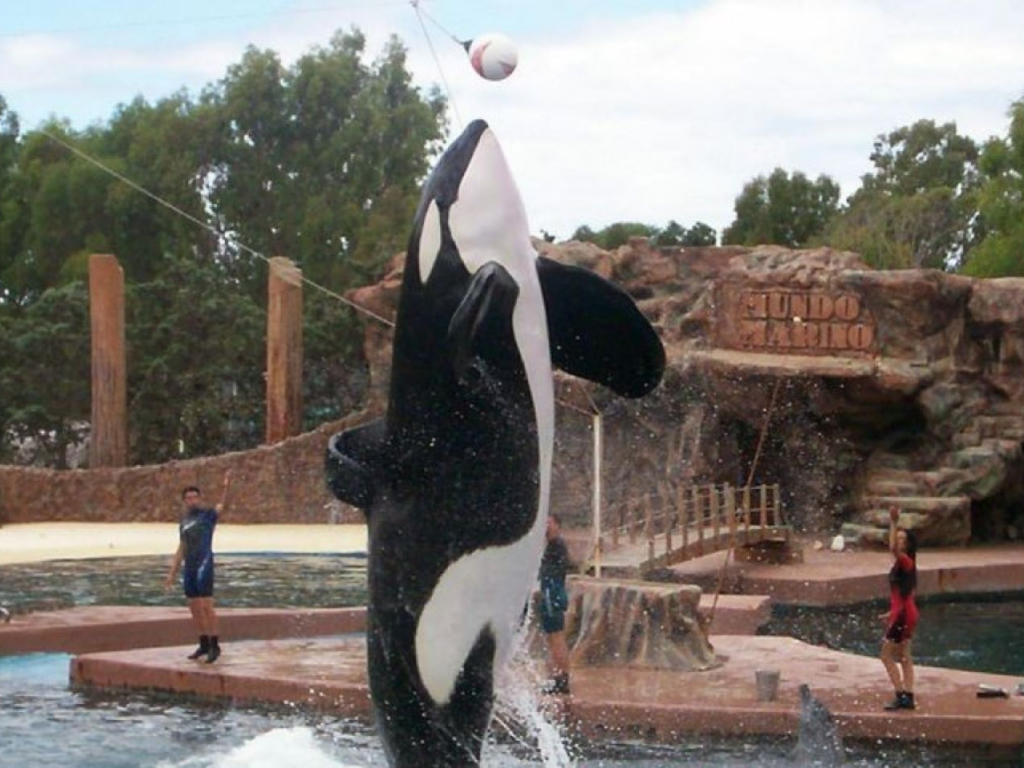

BUENOS AIRES, Argentina — At the Mundo Marino, the roar of the crowd reverberated around me. Flags covered the stands creating a festive atmosphere as music played. Cheers, shouts, and applause filled the air. Sitting there with my camera in hand, I waited. Suddenly, Kshamenk the killer whale broke the surface of the water. He soared gracefully before landing on a platform directly in front of me.

The first sight of him felt gut-wrenching. You could see the bones in his ribs and skull. His dorsal fin drooped, while a large bulge protruded behind his head. As I watched in shock, I felt my chest tighten and I lost my breath. I followed him throughout the show in complete disbelief, as I realized the horror of his story. I snapped photos repeatedly as tears blurred my eyes. One by one, the tears fell as I realized he would die if he stayed like this.

Read more animal rights stories at Orato World Media.

Lawyer learns about Orca’s heartbreaking captivity at Mundo Marino, collects testimonies

During the COVID-19 Pandemic, I stumbled upon the story of Kshamenk, a killer whale. Videos, images, and testimonies painted a heartbreaking picture. In one video, I watched him floating still, as if suspended in the water for hours. His breathing was the only sign of life in the tiny concrete pool that boxed him in. Then, I heard a piercing cry that sent a shiver down my spine. Trapped in that space for 32 years, Kshamenk remained cut off from the outside world. The smell of the sea remained out of reach.

I began collecting testimonies and learned Kschamenk entered captivity at three years old, along with his family, in a bloody, sinister hunting operation. The difficult maneuvers of capturing and transferring them on ships caused the death of two other orcas in the group.

The other adult orcas, initially trapped with the calves, could have swam away. Yet, they stayed, making sounds and gestures. The workers said it felt like kidnapping a small child from its mother’s arms. Kshamenk’s brother, who arrived with him at the aquarium, took his own life by repeatedly smashing his head against the pool walls, leaving them blood stained.

After cleaning it, they placed Kshamenk in the same body of water where his brother died. The testimonies and images overwhelmed me. Unable to hold back tears, I decided immediately to take on the case.

Mundo Marino’s inhumane Orca breeding spurs lawyer to draft protection bill

Kshamenk’s enslavement began at Mundo Marino. At first, he lived with another female orca named Belen. At 13 years old, they forced her to mate with him. The irreparable consequences of making her mate before she was old enough caused trauma. Belen could never have offspring, suffering countless miscarriages. Her health deteriorated and she died young.

Tests revealed Belén died pregnant. It felt like butchery. At one point, they owners attempted to transport Kshamenk out of the country as a breeding stallion. However, legal issues prevented it. As a result, they trained him to ejaculate. With no female orca around, they used Floppy, a small bottlenose dolphin, to stimulate him. The process proved horrifying and disgusting.

After being stimulated by the dolphin, Kshamenk lay on his belly while they dried his genitals with towels. They placed an artificial vagina on him to collect the sperm, using electroejaculation or manual stimulation. Testimonies state they extracted quantities far beyond average, which proved extremely harmful to his health.

With my team, we had gathered ample evidence and, along with other lawyers, drafted a bill, which we submitted in July 2022. However, bureaucratic issues delayed it, and the authorities shelved it. We resubmitted it at the end of 2023 and now awaiting new resolutions.

Documenting Kshamenk’s deteriorating condition: an Orca on the brink

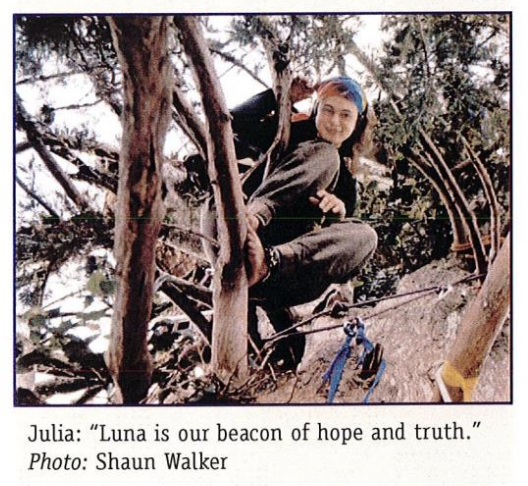

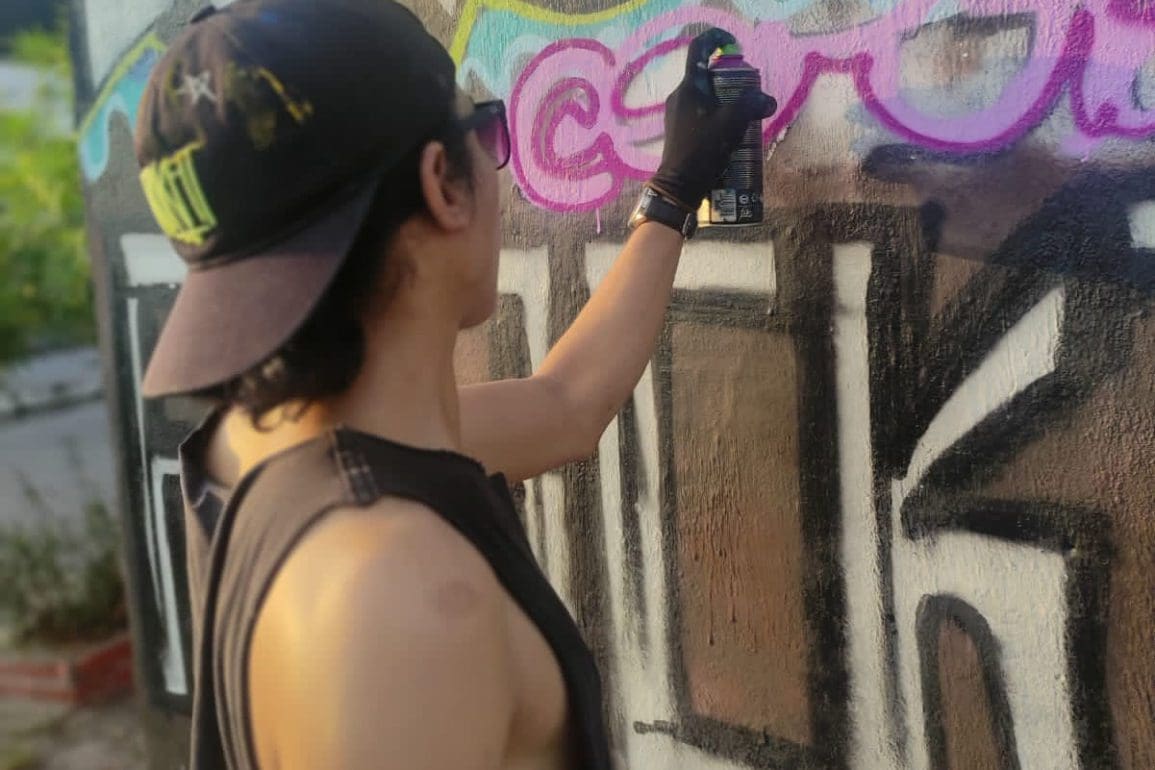

To address Kshamenk’s situation, we implemented a plan to document the decline in his health. The only way to do this was to capture high-quality photos and videos for specialists to analyze. Mundo Marino, the company housing him, refused to permit direct examination by a specialist. Accompanied by a photographer, I headed to the aquatic park to gather evidence.

I arrived at Mundo Marino and sat in the bleachers by the show pond. The overwhelming noise of music, cheers, and applause filled the air. Argentinean flags draped the stands as the World Cup drew to a close. With my camera ready, I documented Kshamenk’s condition in horror. His trainers rewarded him with food for each trick he performed.

The scene echoed the testimonies of former company employees, who recounted how they starved him to make him follow instructions. The sight of him deeply impacted me. It broke my heart to watch the trainers caress Kshamenk, knowing how brutally they had beaten him. They even used electric shocks to control the killer whale. Every now and then, a sudden rush of tears streamed down my face.

At one point, they made him leap. His massive body soared out of the water like a star, and in that moment, I could see in slow motion every detail that reflected his suffering. My heart pounded, my breath grew heavy, and my body shuddered. The sound of the camera clicks echoed in my ears, mingling with the music and distorted voices of the trainers. Screams and applause from the audience closed out the show.

The fight to free Kshamenk continues, activists await resolution

After developing the photos and laying them out on the table, a specialist confirmed our fears. Kshamenk’s health prognosis looked bleak. If nothing changed, he would likely die. With this knowledge, we filed a collective action and await further development. If this continues, Kshamenk’s end will come soon.

It seems impossible to view Kshamenk’s captivity as anything but inhumanely brutal. We fight to free him from this tragedy so that he will not live in agony until his end. He deserves humane, dignified treatment. We must not lose sight of his powerful spirit.

After 32 years of exploitation and captivity, Kshamenk serves as a symbol in the fight for animal rights in Argentina and around the world. He remains the only orca still living in captivity in South America. I refuse to stop fighting. Kschamenk will be free.