Uruguay man endures devastating spinal injury, starts NGO for children with disabilities

I moved to cover the ball as one of the opponents took off toward it. When I could not grab the ball in time, I threw myself forward to cover it. At that moment, the other player tried to kick it. I felt the blow land on the back of my neck. An electronic shock rushed through my body, and I immediately felt cold.

- 3 years ago

October 9, 2022

MONTEVIDEO, Uruguay — When I was five years old, my father passed away. On September 12, 1978, he called us and said, “I’ll be home later,” but he never arrived. The next day, they found his dead body. Authorities never discovered who killed him or why. The news devastated our family.

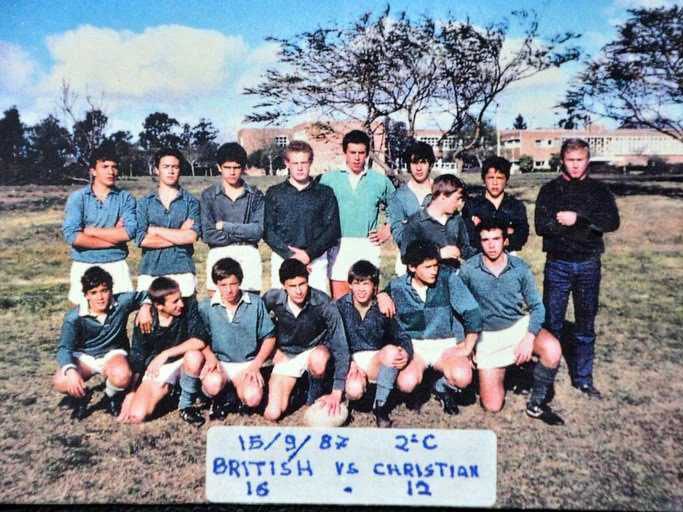

Life moved forward, until a second blow struck our family. While playing in a high school rugby game, I endured a paralyzing neck and spinal injury. I became a quadriplegic and entered long-term recovery. Yet, I never game up.

I went to college and then, in 2019, I started an NGO called El Palomar in Uruguay. We support children with disabilities through inclusive education. This is my way of giving back.

After father’s murder, young man turns to sports but experiences a devastating injury

Authorities never discovered who killed my father or why. The news devastated our family. As a housewife, my mother suddenly had to provide for me and my siblings. I began working in the fields to help. My mother rolled up her sleeves and got things done. I never saw her cry or complain.

In school, I became very introspective. Sports played a prominent role in my life. In my primary sport of rugby, I felt tall and strong. One day, we played a game on the school club court. The first half progressed well, but 20 minutes into the second half, I began to feel fatigued.

I told a teammate, “I don’t have the strength to push on.” When the full back kicked a long ball, the whole team went forward but I stayed behind. They returned the kick, and it went down the middle toward the goal.

I moved to cover the ball as one of the opponents took off toward it. When I could not grab the ball in time, I threw myself forward to cover it. At that moment, the other player tried to kick it. I felt the blow land on the back of my neck. An electronic shock rushed through my body, and I immediately felt cold.

I fell face down. It seemed impossible to stand up. A doctor came to me immediately. “It’s the spine,” he said. An ambulance arrived quickly. The audience applauded as the paramedics carried me off the field. At 4:00 in the afternoon they rushed me to the British Hospital.

Facing the long road to recovery alone in a hospital room

At the hospital, the doctors performed a tomography and realized something serious happened to my neck. They cut off my shirt. I looked up to see my siblings. My mother, who had taken a trip, could not be there.

The staff put me in a tube for an MRI and I passed out. By the time I awoke, the darkness of evening had set in. I felt a sharp pain. A collar with weights attached sat on my head to deflate the area. I could not move my legs and they hurt. When I opened my eyes, I saw my uncle and a cousin. Desperately, I asked them to massage my legs and went back to sleep.

The tests revealed two broken cervical vertebrae (the fourth and fifth), displacement of the disc, and an impact on the spinal cord. The second time I woke up, they had moved me to an intensive care bed. I had stitches from an operation. The sounds of the equipment hovered around me. I wanted to move but could not. I asked the first doctor I saw what happened. He said, “You had an accident and injured your spine.”

Nights in the hospital felt endless. I only received visitors early in the morning through the afternoon. The rest of the day, they left me alone. The silence of the hospital felt terrible. At that point, as a quadriplegic, I tapped into memories while lying in bed. The memories helped me sleep in peace and face the challenges of each new day. The images of that time remain vivid to this day.

Man recovers from being a quadriplegic, serves people with disabilities in college

A month later, with a little recovery, I began to move a finger on one hand. We traveled to a rehabilitation center in the United States where I shared a room with people worse off than me. Some had no feet or limbs. Staying in that environment proved difficult. I could not see my family for two months and felt so alone. Yet, my stay at the center strengthened me mentally.

Suddenly, I began to mature. At 20 years old, I had to learn everything all over again. I had to learn to tie my shoes with my mouth. It took four hours to get dressed on my own. I cried when I had to get in a wheelchair and when things did not work out, I battled forward. Slowly and with much faith, I began improving.

One day, I moved my left hand. I decided to write a farewell letter to my other hand, since I would never use it like before. It took a year to walk again, to go to college, or even to go out to a restaurant. Accepting my disability took enormous effort, but I needed to resume my life outside the silence and emptiness of the hospital. In time, I moved forward and began attending university in Spain.

Two friends and I decided to team up and start a project called PAI. We wanted to provide support to students with disabilities, so we made recordings and notes to give to blind students so they could study. We also transported wheelchair-bound students to school by car. I began to feel my calling, to help people with disabilities.

Motivated by his suffering, Uruguay man launches NGO and finds purpose

The experiences I had during the PAI project in college stayed with me. Later in life, I remembered them and the idea for El Palomar emerged. In 2019, I gathered my close friends and proclaimed, “I want to start an NGO!” They came on board and for our first project, we built ramps for disabled people.

Today, we promote inclusive education, giving scholarships to schools for children with disabilities. We also contemplate the infrastructure and human needs of disabled people so they can function better in society and participate more wholistically in the academic environment.

For me, this work means giving love selflessly. I chose to work with children over adults because older folks can be afraid or prejudiced against people with disabilities. Children, on the other hand, possess the potential to teach their parents.

We provide new opportunities for children who see life from the viewpoint of a wheelchair, and those opportunities extend to their families as well. Starting my NGO felt like I brought together all my family’s suffering and turned it into something positive, in memory of my father.

Now, I can show people with disabilities they can do anything they set out to do. They can touch the sky. Thanks to my disability, I understand the importance of receiving an inclusive education where everyone feels welcomed and supported.