City faces worst dengue virus epidemic in history, queues at medical facilities stretch for blocks

With each patient I treat, I feel the weight of their suffering. Their bones ache, they can barely stand, and they burn with fever. I see patients vomiting, dehydrated, and plagued by gastrointestinal discomfort.

- 2 years ago

April 17, 2024

BUENOS AIRES, Argentina — As I step into the clinic each morning, the reality of the situation in Buenos Aires greets me with sobering clarity. I am witnessing what is being called the worst dengue virus epidemic in history.

Every day, I meet patients suffering from fevers that soar to 42◦C (107◦F). They arrive in a state of utter exhaustion, barely able to stay upright. The dengue season arrived earlier than usual this year, catching everyone off guard. Typically, the most critical stage of the virus’ annual lifecycle occurs later in the year.

With the unexpected surge taking us by storm, we are looking at 180,000 cases of dengue fever and 129 deaths. The upward curve in cases proves alarmingly steep.

Read more health stories at Orato World Media.

Battling dengue: A skyrocketing disease

Walking to work, the queues of people stretch for blocks outside the medical centers. Everyone I encounter either had dengue fever, suffers from it now, or knows someone affected recently. As a frontline doctor, when desperate patients arrive, I scribble directions for self-protection against the virus on a piece of paper with a pencil. In the absence of official leaflets, we create homemade means to spread the message.

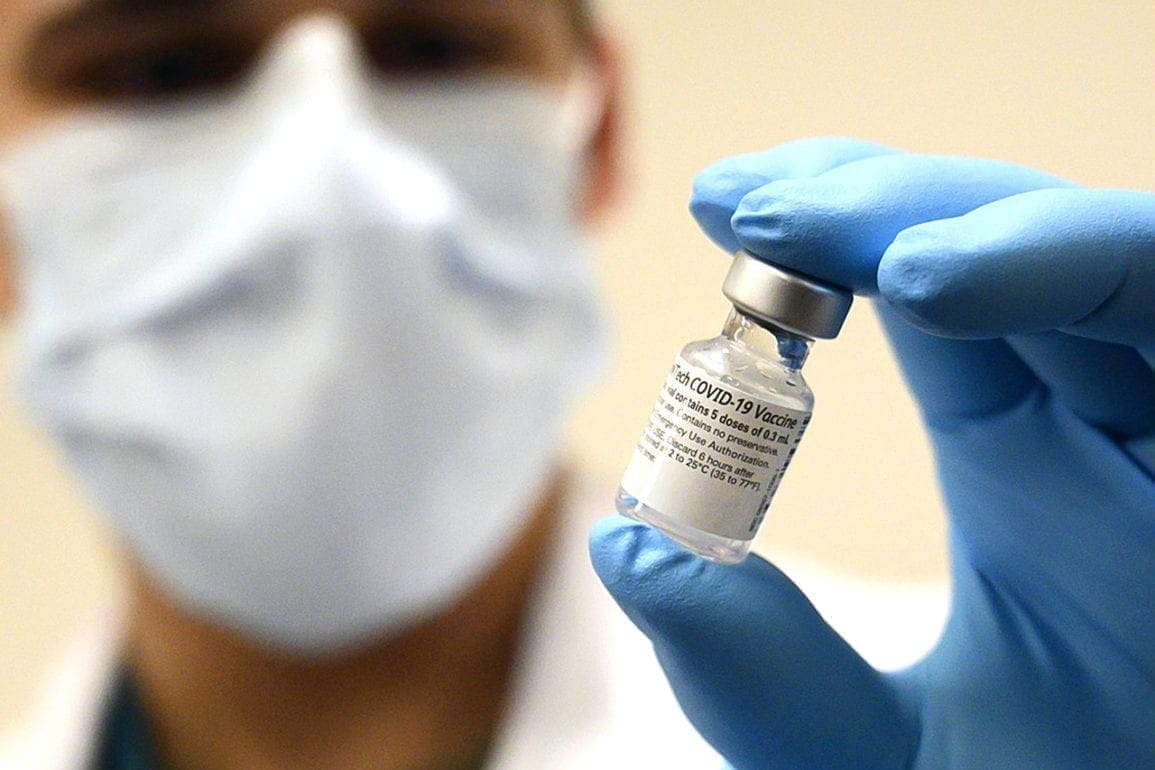

I find myself immersed in the debate about including the dengue vaccine in the mandatory immunization schedule but watch as the national government seems reluctant even to acknowledge the outbreak. Sadly, the severe economic crisis in Argentina makes the vaccination unaffordable for most of my patients.

With each patient I treat, I feel the weight of their suffering. Their bones ache, they can barely stand, and they burn with fever. I see patients vomiting, dehydrated, and plagued by gastrointestinal discomfort. An acute migraine often settles behind their eyes, making the pain unbearable.

These patients lose their appetite and thirst, yet they wait for hours to be seen. Some try to remain standing, while others sit on the floor. The brutality of the situation feels utterly overwhelming. Taking care of myself becomes a real challenge. What makes this epidemic particularly dramatic is the lack of repellents to avoid mosquito bites. The shortage of this crucial defense mechanism started in March, just as we entered peak season.

In the last 15 days, as the cases peaked, the crucial repellent became almost impossible to find. Staff at supermarkets, stores, and pharmacies echo the same phrase: “We don’t have any.” Where available, prices became astronomical. A single repellent bottle costs four to nine dollars. Meanwhile someone living on a pension may earn 200 dollars a month, and a bottle lasts just three days.

Everyone has Dengue

In some of the neighborhoods where I work, I see the worst possible scenarios. People struggle to access clean water for drinking or bathing to reduce fever. Mothers push babies in strollers without tulles or mosquito nets because they cannot buy them. Neighborhoods remain surrounded by garbage and stagnant water reservoirs – a perfect breeding ground for mosquitos. As I pass through these areas, it feels like living in a horror movie.

Every single day, new cases emerge, and the fear remains palpable. I see people in desperation, barely venturing outside anymore. One neighbor will come down with dengue fever, then the person across the street, and everyone knows it could be their turn next. The residents live in a constant state of vigilance. They fearfully rush to the safety of their homes, closing doors and windows. The feeling of dread multiplies as the number of cases rises.

Every day, without fail, I see patients with fevers reaching 42◦C (107◦F). They arrive in a state of utter exhaustion and dehydration. They stagger, convulse, hallucinate, and vomit. Patients become disoriented from time and space. When their bodies reach such high temperatures, the proteins begin to break down and die, an extremely serious health situation.

Some patients report slight improvements, then spend the entire day bedridden. They writhe in pain, holding back screams. The medication Paracetamol barely provides relief. Their joints completely stiffen and they suffer intense headaches, with a sharp pressure just behind the eyes, making it difficult to see or focus.

I worry my long-term patients will leave and I’ll never see them again

I recently encountered a particularly heart-wrenching case. A taxi rushed a critically ill seven-year-old girl to the hospital suffering from dengue fever. She bled from several parts of her body, and despite efforts to resuscitate her, she rapidly lost blood from her nose and mouth. The bag used to administer oxygen turned red.

Tragically, she died minutes after arriving at the emergency room, a victim of a preventable case of dengue fever. We all felt devastated and traumatized. The pain feels immense, then and now. Shock and grief overwhelmed this little girl’s family, as well as me and the entire medical team, as we all cried.

Many patients I treated for years now leave my office and I have the haunting thought I may never see them again. I try to avoid too much eye contact so they cannot see me cry; and I embrace others as if it were our final farewell.

This entire situation fills me with anger and sadness. Walking through the long lines of people waiting for care crushes my heart. I see elderly men and women, and mothers with babies and children. Yet, every day, I go to the hospital or health center, don my white coat, and fight with the tools I have, striving to make this world a better place. I will never give up

We need the government and public to take action against the dengue virus

At its worst, I see cases where patients arrive hemorrhaging. They bleed from the gums or nose and red dots appear on the skin. This alarming sign can lead to severe complications, like the little girl I encountered. The other worry comes with being infected by the dengue virus twice in the same year. Once a person recovers, they become immune to the type of virus that infected them, but not the other three serotypes. An infection with one serotype followed by a different serotype increases a person’s risk of severe symptoms and death.

In a short while, everything will likely worsen, with the highest peak of infections expected in 15 to 30 more days. We, in our trenches, hope to defend and save people. Soon, we might stop talking about dengue epidemics and start talking about endemics, which is deeply concerning. The disease is advancing relentlessly, putting everyone’s life at risk.

Halting this epidemic requires public education to prevent the spread of the dengue-transmitting mosquito. However, national campaigns remain scarce. In the past, we would see a few cases of dengue fever in December, and the numbers would gradually increase until March. However, global warming has changed the game. Rising temperatures and more frequent extreme weather events have led to a significant increase in the mosquito population. As a result, we now see dengue cases throughout the year.

For every person who shows symptoms of dengue, there are three other asymptomatic individuals who go unregistered in the health system. This is a major concern. In public hospitals, we have activated special protocols for patient care. In some provinces, non-urgent surgeries have been rescheduled to free up beds. The medical wards are overwhelmed with patients. Something must be done.