The book that came from the voices in my head

I was diagnosed with bipolar disorder after spending almost a week on the brink of a psychotic break following a holotropic breathing workshop.

- 5 years ago

March 16, 2021

BUENOS AIRES, Argentina — Don’t stop breathing.

I could feel my partner’s breath brush my ear as they whispered the words.

Stopping is not allowed.

Hallucinations flooded my mind, clouded my senses. The real world was peeled back, layer by layer like a rotting onion.

Don’t stop breathing.

Outside, in the real world, my body fought against those who sought to calm me. For hours, my body wanted to strip down, naked, and fight for my life, while my mind remained fogged by fleeting memories.

Don’t stop.

Controlled breathing

My name is Greta Lapistoy. I’m 44-years-old, and I have been in psychiatric treatment for 15 years.

I was diagnosed with bipolar disorder after spending almost a week on the brink of a psychotic break following a holotropic breathing workshop.

After the session, my head felt as if it would explode from the flood of thoughts that came into my mind.

“If I don’t write, I’ll die,” I thought over and over.

A week later, unable to sleep or eat, I decided to ask for help.

My writings, scribbled on the edge of an internal explosion, became the basis of my book published to raise awareness of mental health.

The explosion

Happy people don’t go to these kinds of places. But I wasn’t a happy person. My life was full of terrible feelings that left me unable to enjoy life.

That’s why, after trying several options without any result, I participated in a holotropic breathing workshop.

With little information about the exercise, I went to a house with 14 people and a therapist who was guiding the process.

We were grouped in pairs and instructed to breathe rapidly for two hours to oxygenate the brain. If one person slowed down, their partner would whisper in their ear, “Don’t stop breathing.”

Ten minutes into the exercise, I began to have hallucinations: memories, images, thoughts. It felt like I was leaving the real world. But, in reality, my body fought against the process.

Several people had to grab hold of me, but I only fought.

After several hours, I began to calm down.

The day ended, and I walked home without knowing what to expect.

The day after

My mind was full of thoughts, triggered one after another. They stepped on each other without any discernable connection.

I spent my first three days in this fractured mindset as sleep and food evaded me.

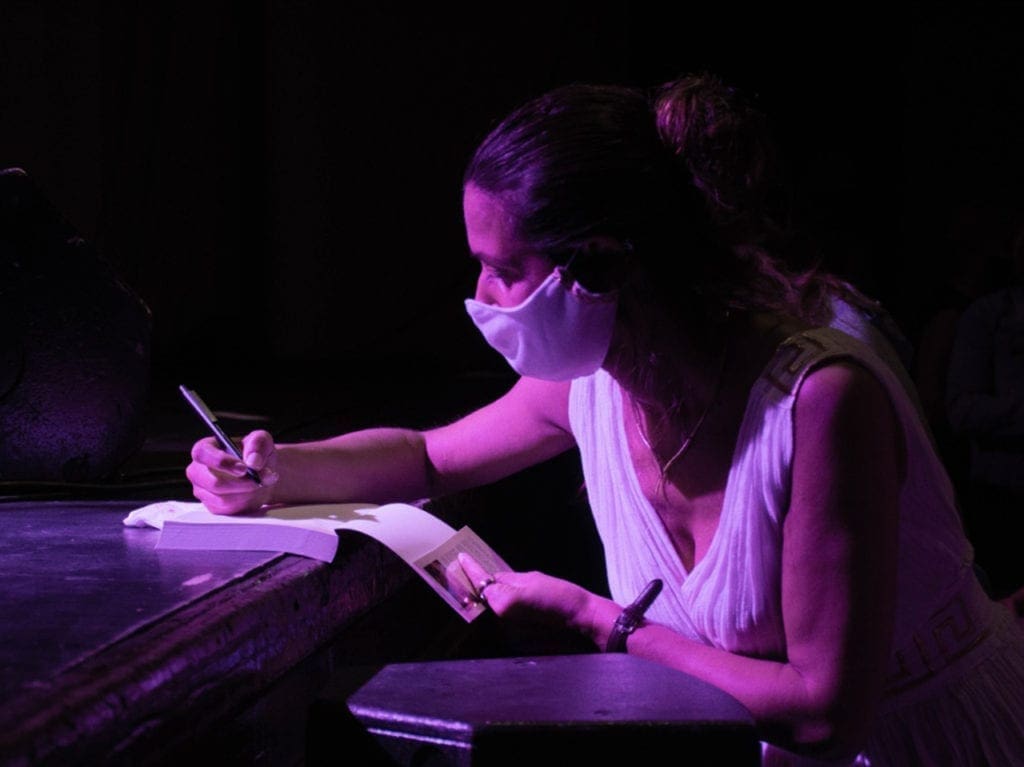

Locked in my room, the rollercoaster of random thoughts soldiered on. I scrambled to unload my thoughts on paper.

“If I don’t write, I’ll die,” I repeated.

On the fourth day, I began to sleep less than three hours.

Within a week, I could no longer fall asleep and could not eat anything.

After seven days living on the brink of a psychotic break, I had lost 36 pounds.

Call for help

I no longer had any strength. Time had lost its bearing.

With my last breath, I wrote a letter to my dad asking him to accompany me to see a psychologist.

I don’t remember exactly what I said to him. He never showed me the letter.

That day was my new beginning.

I was diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

The hidden story

The psychoanalysis sessions made me hypothesize that the holotropic breathing workshop detonated the bomb that was dormant in my mind.

The life I led before was wandering. Neither my partners nor my jobs lasted. Every time I started something new, I jumped in full of energy but, after a few months, a strong depression developed and would not let me continue.

The unconscious handles us as it wants. It brought back memories that I thought were lost.

When I was four-years-old, my little sister was born and passed away after 10 days. My mind had erased those memories. My parents had told me that she had gone on a trip to heaven and I waited for her return for four years.

That pain that I thought I had overcome ran deeper than I imagined.

Taboo life

After my diagnosis, I began to define myself as bipolar. Every time I have a date, it’s the first thing I say.

Today, I understand that this disease will follow me throughout my life, but I am more than that.

During my treatment, I was able to obtain a university degree, a technical degree, and a diploma.

My life is the same as anyone else’s: I get up every day, go to work, and put effort into my projects.

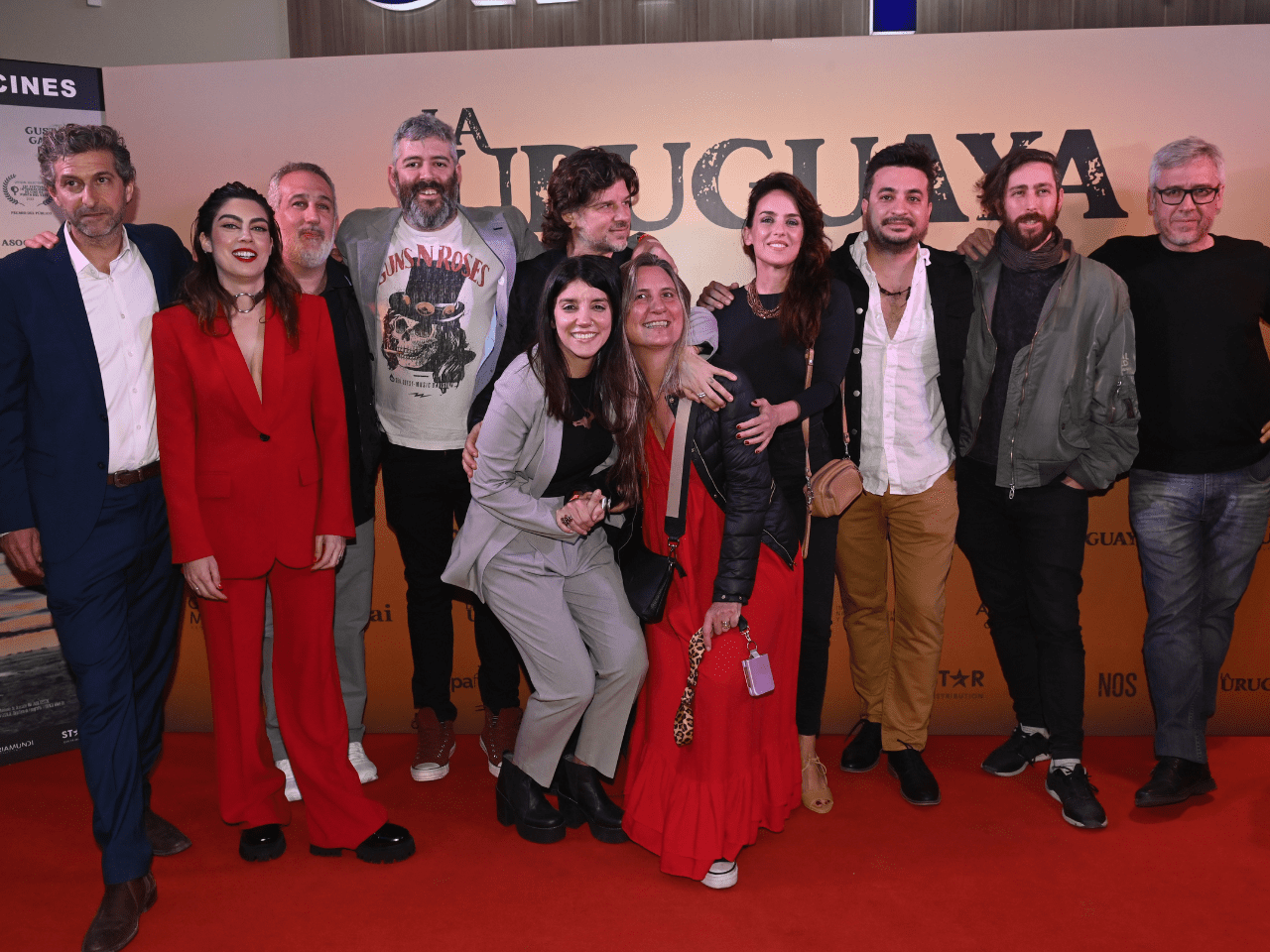

My recent project, a book titled “Unconsciously True: A Volcano called Bipolarity,” was recently published.

After much thought, I published it to raise awareness about mental health.

Hopefully, over time, the stigma surrounding mental health will fade.

Stigma, a fear of what others will say, can lead to stopping the medication.

But, when the disease is treated, normal life can be led.

My new life

I feel complete. I’m a different person than the one who walked into the holotropic breathing workshop 15 years ago.

With three degrees under my belt, I have a job that I love and a family that loves me.

I have bipolar disorder, but I also have thousands of other characteristics that make me who I am.

I am more than my disorder.