North Face founder funded national park project in Argentina, near-extinct giant otter found

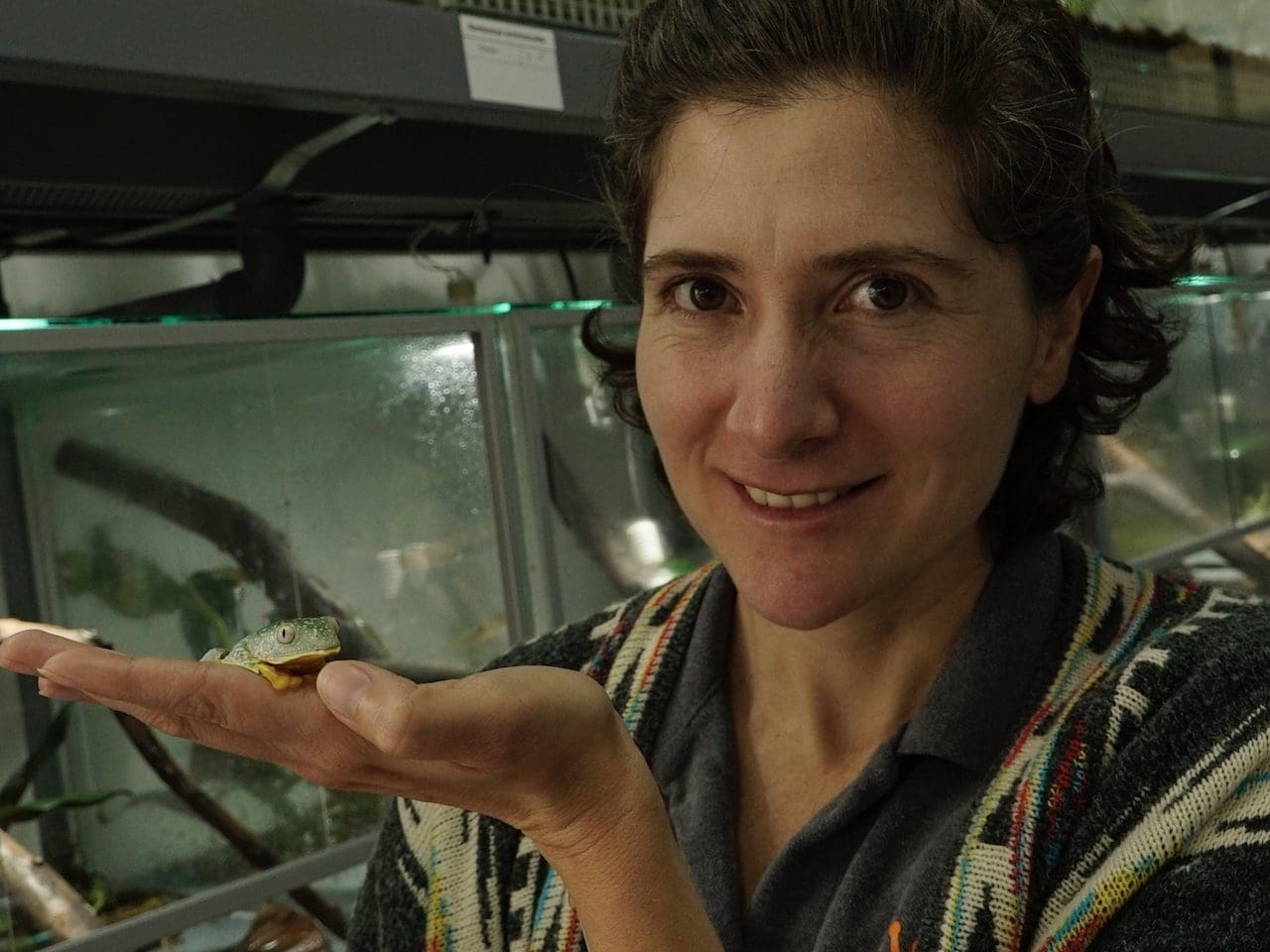

In the field, I live in an African-style tent protected by a mosquito net called biological stations. A typical day includes preparing pens for otters or changing collars on jaguars when the batteries die.

- 3 years ago

October 21, 2022

CHACO, Argentina ꟷ As my kayak moved down the Bermejo River in El Impenetrable National Park, I spotted something in the water. I remember the day perfectly. Almost by accident, I photographed an animal thought to be extinct in the region – the giant otter.

My legs weakened, making feel like I was falling, and excitement took over my body. My heart began to race. With the loss of habitat and the ability to hunt, we feared the largest otter in the world may have vanished from Argentina. When the wild otter appeared in front of my camera a year ago, we thought of a project to protect it and help the species thrive.

A giant otter appears in Argentina after decades of absence

The giant otter inhabited the basins of the Paraná and Uruguay rivers, but completely disappeared in Argentina. Environmentalists recorded the last of the species in the 1980s in the province of Misiones and was never seen again.

After my encounter with the giant otter, we started a project to reintroduce it in the Ibera Wetlands. Several family groups existed in protection but had not been released into the wild. They reproduced in captivity. We placed several camera traps to photograph the otter and caught images of the young male adult.

Most likely, the animal came from the Pantanal [The world’s largest freshwater wetland fed by the Paraguay River]. We assumed it swam across the Paraguay and Bermejo Rivers during the Pandemic, when little human activity occurred there. Alternatively, it may have represented an undetected remnant population in Argentina.

Giant otters live in family groups but this one appeared to be a solitary individual. We observed him for several months then stopped seeing him. In November 2021, and again a month ago, footprints appeared on the banks of the river.

In response, we plan to build pens, half in the water and half on land, to deliver a captive female from Ibera. We hope to join her with the wild male while keeping her anchored to land.

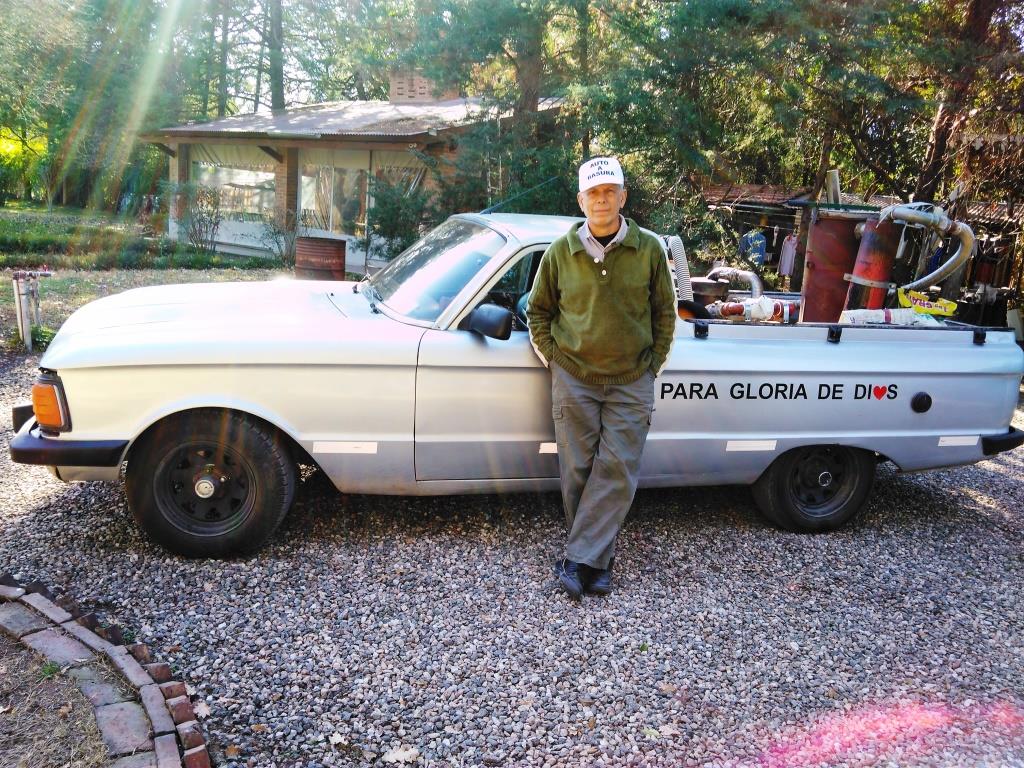

Conservation projects funded by Kristine and Doug Tompkins of The North Face and Patagonia

El Impenetrable National Park, where the giant otter appeared, came into existence in 2014 with the help of Rewilding Argentina and Tompkins Conservation, the organization created by Kristine Tompkins and her late husband, Doug. The couple used the money from their companies The North and Esprit. Kristine also served as CEO of Patagonia. Thier work has protected more than 14 million acres of land in Chile and Argentina. I work in the lands they preserved.

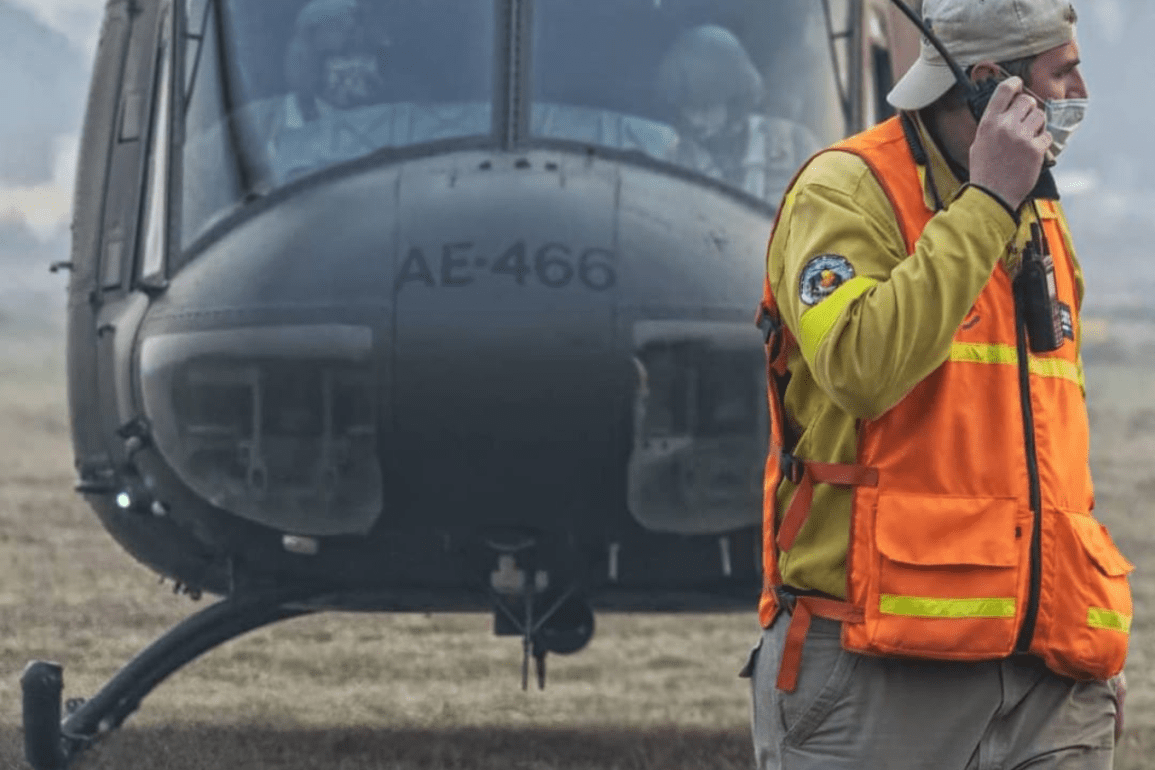

In El Impenetrable National Park, we focus on preventing poaching, then seek to reintroduce and protect different species into the Chaco region of Argentina. The two otter projects I work on include growing the giant otter family group in Ibera through captive otters and integrating captive and wild otters in the park.

Day-to-day, I move between the two projects, living in a field of action. The work creates an entertaining life for me. I spend some time in a small office in Buenos Aires, but most of my hours include roaming the parks and their surroundings. I interact with work groups in each area, sharing our ideas and vision with one another.

In the field, I live in an African-style tent protected by a mosquito net called biological stations. A typical day includes preparing pens for otters or changing collars on jaguars when the batteries die. In this magical, unique environment, I fight for nature. As the parks take shape, we bring in missing wildlife.

Because the land suffered immensely from degradation, we focus on local development to change the matrix of human production in these territories. For example, as we remove livestock from unsuitable environments or stop the logging of nonrenewable centenary trees, we develop an economy of service. We focus on nature tourism linked to wildlife observation.

Group reintroduces multiple animal species into Argentina parks

This work generates support for the creation of these large parks, reintroduction of species, and simultaneously to help people improve their income and quality of life. Yet, when we introduced some species, they quickly disappeared. People saw them as problems. Now we work to transform the people’s view, to see this as an opportunity. More parks and fauna will lead to higher incomes for the development of the community.

The otters play a vital role in this balance. Giant river otters, as top predators, exert regulatory influence on the aquatic ecosystem. They regulate fish populations and contribute to the health of the aquatic ecosystem.

The first time I saw the giant otter emerge his head from the water, I witnessed a stunning creature – a huge and spectacular animal. The giant otter can measure 1.8 meters long (almost four feet). Adults weigh more than 30 kilograms (about 2.5 pounds). They appear confident and curious. We must protect them and the park – a jewel of biodiversity.

To take on the comprehensive, complex task of reversing species extinction, we work with a very large group of people. We bring back animal species which lived in historical times and reintroduce them, focusing on their ecological roles.

An ecosystem can degrade when a species disappears, worsened by climate change, pandemics, and other environmental problems. To date, we have brought back pampas deer, the giant anteater, the collared peccary, the jaguar (South America’s top predator), and the ocelot.

Creating parks throughout Argentina, we have likely pioneered the largest species reintroduction project in Latin America.