Judge who dedicated her time to saving Sandra details emotional moments with the orangutan

In the room awaiting her departure, at the Ezeiza terminal, we gave her fruits like kiwis and oranges through a slit in the enclosure. She peeled them and threw the shell through the window. I looked at her and began to cry. It seemed like my way of saying, “Everything will be okay, Sandrita, alright?” She blinked back at me.

- 3 years ago

March 17, 2023

BUENOS AIRES, Argentina ꟷ In 2015, a file containing information about a female orangutan named Sandra landed in my hands. As a lawyer and judge, I pursued a vocation to defend the innocent. With animals, I witnessed the lack of protection they endured. Like children, animals represent pure innocence. Yet, children have institutions to protect their rights. For animals in Argentina, the only protection I could rely on included a vague code outlining them as property of human beings. I took on Sandra’s case.

Read many more animal rescue stories from around the world.

The words of a philosopher echoed through my mind: “We have to look for a new hospitality towards living creatures.” As I perused the file, I made a decision. I needed to be the kind of person to protect her. It felt like it was meant to be.

I recall holding that file in my hands so vividly. The excitement that pulsed through my body made me shake. Sandra’s story moved me so remarkably, my heart throbbed. Not only would this case be a pivotal one for my career, it would be an incredible opportunity for Sandra. Intuitively, I knew I would fight for her.

[Sandra the orangutan, who was born in Germany, spent 25 years in captivity at the Buenos Aires Zoo. In early reports, some news outlets called the zoo “antiquated.” For over a decade, Sandra had zero interaction with any other orangutans. The animal welfare group known as La Asociación de Funcionarios y Abogados por los Derechos de los Animales (AFADA) took Sandra’s case to court to request “personhood” rights. The Buenos Aires Zoo closed in 2016 and underwent conversion to the Buenos Aires Eco-Park.]

Her eyes hypnotized me: meeting Sandra the orangutan

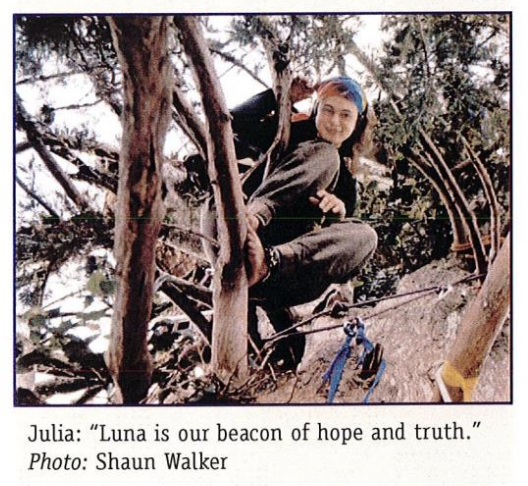

As we processed the file, I stayed away from the zoo. I saw it as a place of captivity and it made me uncomfortable, so a member of our team went on my behalf. Once a jury was assigned to the case, I began weekly visits. I strongly sensed something very unique and different was coming the first time I went to see Sandra. I wanted to connect with her as a non-human person versus a thing. When I arrived, the place felt so loud and crowded. In the open enclosure, my heart throbbed and I felt uncomfortable. For me, it felt like I needed to overcome the conditions of captivity myself.

I could see the stress experienced by the orangutan, and intimacy became difficult. Out loud, I declared, “Can I please have a moment alone with her?” When everyone left, I sat and watched. Sandra hid her face all the time, under cardboard or a piece of cloth. Her hands looked amazingly similar to human hands – so soft. Like a feline, she moved delicately and paused to look. Her eyes became the part that truly conquered me. Perfectly round, they felt hypnotic.

The enclosure simulated rock formations with stones everywhere – contradicting the Malay meaning of orangutan: “man or woman of the forest.” Sandra had no trees to play on or live around – only those off in the distance, outside the zoo. I felt a sense of desperation seeing her locked up in a small cage, so I tried to convey my intent. I would get her out of there. She would live in a beautiful and better place.

The hard years, fighting ridicule and attacks

From the beginning, we faced rejection. Throughout the entire process, people spoke in derogatory ways about Sandra and me. They called her a “monkey” and referred to me as “the woman who wanted to give rights to a monkey.” Even news outlets attempted to defame Sandra and the case. As I ate breakfast in the morning, I opened the newspaper to articles like La mona vestida de seda (The monkey dressed in silk), ridiculing the work. Those years proved difficult. We pushed on.

The scientific community rallied around the case, contributing in ways of the utmost importance. Primatologists from Argentina, the United States, Canada, and Australia came to consult. It became clear through their expertise that Sandra, born in captivity, could not return to her natural habitat. Yet, the most intense moment arose before the resolution of the court declaring Sandra a non-human person. Suddenly, jokes and ridicule exploded everywhere. I hid my feelings but my spirit plummeted at times. I soon realized, I had a life before Sandra, and a different life after.

Clearly, the resolution did not give Sandra the same rights as humans. Nevertheless, the media ignored our purpose: that Sandra deserved the demonstration that her life was respected. The headlines took another turn: “Now the monkey will vote.” The error occurs here when mankind stands on the throne of life. I began to see how human beings take things for granted. No one stopped to think about the role animals fulfill. Fortunately, in January that same year, France introduced a new categorization for animals. They broke with established norms and deemed certain animals as “sentient beings.” The courts had begun to see the sacred link we have with animals, and as humans, it gave us the opportunity to change our perspective.

Saying goodbye and sending Sandra the orangutan to Florida

While interest waned in Argentina, and three times the government failed to attend important gatherings, greater interest spurred from abroad. Soon the time came for Sandra to be transferred to a more humane location in Florida, in the United States. In September 2019, four years after the jury’s resolution, a truck arrived carrying a large metal box, gaggled by ropes. Two things happened that day.

Sandra cleaned her enclosure. During her time in captivity in the Buenos Aires Zoo, she saw how people cleaned and she imitated them. Then, just before entering the cage, she reached for her emotional support blanket, and took it with her. It confirmed what I already knew. Sandra feels. She cleaned her enclosure before she left, and she took something on her trip to the unknown. Surely, Sandra felt as afraid as I did.

In the room awaiting her departure, at the Ezeiza terminal, we gave her fruits like kiwis and oranges through a slit in the enclosure. She peeled them and threw the shell through the window. I looked at her and began to cry. It seemed like my way of saying, “Everything will be okay, Sandrita, alright?” She blinked back at me. I felt consumed by worry. Given the temperature on the day of travel, we decided she would travel without food, drink, or sedation. That worried me even more.

“What will come of all of this,” I wondered. A unique and unrepeatable anguish invaded my spirit. My legs weakened as fears of her death hit me. If Sandra died, it would feel like my life got buried with her. I wasn’t sure I could return from that emotionally. What I wanted, more than anything else, was to protect her.

Setting an international precedent in the protection of non-human persons

As the airplane left, rising up into the sky, oh how I cried. My skin bristled as we followed the flight in an app. As the dots appeared on a map on my cell phone, I exclaimed, “That is her! Look at where the flight is!” We followed her the whole way as we cried and hugged one another. When Sandra arrived at her destination in the United States, we celebrated. Sandra had succeeded. As I let out a deep sigh, I dried my tears, and my heart ached with happiness.

I became a judge at an age which I viewed as half my lifespan. Over the years, I accepted unusual and unforeseen cases with great excitement and passion. As a result, in 2015, I became the first judge to recognize the non-human personhood of an animal – a decision that has had vast repercussions nationally and internationally.