Photographer wins 2024 World Press Photo contest for years-long project capturing the Mapuche indigenous community

At first, I arrived like a spy, weaving contacts and gradually earning trust. To understand the situation, I engaged in extensive conversations. Over time, my camera became a tool to document their resilience and resurgence.

- 1 year ago

August 25, 2024

BUENOS AIRES, Argentina — Five years ago in 2018, as a documentary photographer for the Argentinean newspaper Página 12, I started a project to investigate sacrifice zones [populated areas with high pollution levels]. Initially, I planned to visit the coal mines of Rio Turbio in Santa Cruz, Argentina, and the salmon farms in Chiloé, Chile. However, I abruptly changed my plans when I heard that Camilo Catrillanca, [the 24-year-old grandson of a prominent Mapuche leader] in Chile’s Araucanía region, was shot dead.

Determined to see and document the aftermath, I drove for nearly 24 hours straight to reach the Araucanía region in Chile. The funeral occurred in the Zonas Rojas, a significant site of resistance for the Mapuche people [the largest indigenous groups in Chile, comprising about 84 percent of the total indigenous population or about 1.3 million people], almost inaccessible to the press.

When I arrived, it felt like I journeyed 400 years back into the past. Surprised, I witnessed Camilo laying in an open casket under the sky, surrounded by hundreds of communities and families. They cooked, conversed, and inhabited around him, creating a communal and reflective atmosphere.

Read more Art & Culture stories at Orato World Media.

Man reveals agrochemical health concerns in Argentina

Before making my way to Camilo Catillanca’s funeral in Chile, I was reporting on a story about a group of teachers protesting the spraying of glyphosate chemicals in villages. At that time, focused on research, I wanted to discover how agrochemical exposure impacts rural communities.

During the project, I uncovered alarming data that mainstream outlets often overlooked, appearing primarily in alternative media. Shockingly, farmers cultivated nearly 60 percent of the country’s arable land with genetically modified seeds and used a staggering 370 million agrochemicals. Alarmingly, this resulted in the highest per capita usage worldwide, causing numerous cancer cases and malformations in the region.

On my vacation, I decided to visit Argentine provinces suffering from health issues caused by agrochemicals. I traveled solo to the hardest-hit areas with my camera in hand, forging deep connections with the people I photographed. Upon arrival, the communities welcomed me into their homes, but one individual stood out: Fabián Tomasi.

Fabián and I developed a deep friendship. He conveyed the health crises through his presence and words, delivering the message without hesitation. He revealed the disturbing situation and guided me on my path. As his body weakened, his awareness and resolve grew stronger. With nothing to lose, he became a symbol of resistance and awareness in his community.

One day, while I was in Paraguay presenting my work to celebrate our friendship, I received the distressing news. Fabián died at 10:00 a.m. on my birthday. Immediately, I returned to Argentina to bid him farewell and see him at peace.

Camilo Catrillanca’s assassination shifts photographer’s focus to the Mapuche community’s struggle

Through my camera, I documented the harsh reality that thousands of Argentines across various provinces faced from exposure to toxic chemicals. This journey led me to craft an extensive photographic essay titled “The Human Cost of Toxic Agrotoxins.” It marked a turning point in my career and personal mission. Consequently, I committed to the path I chose and never looked back.

After I completed my work on glyphosate, I planned to continue researching sacrifice zones, beginning with the coal mines in Santa Cruz, Argentina. However, when I heard about the murder of Camilo Catrillanca, I hurriedly traveled to Chile to attend his funeral and capture the enduring moments.

Camilo’s three-day funeral profoundly impacted me. The Mapuche people revered him as a true “Weichafe” [a warrior in Mapudungun, the native tongue of the Mapuche people]. Witnessing their ability to uphold their worldview and resilience despite external pressures, deeply moved me.

I first connected with the Mapuche people the year before in 2017 after Santiago Maldonado [a young Argentine activist], disappeared while participating in an indigenous rights protest. Argentine Gendarmerie [a government military force] violently repressed the Lof Cushamen resistance in Chubut [a province in Argentina], resulting in Santiago’s death. Santiago’s death sparked my curiosity about who he was fighting for. I wanted to understand the significant issues at stake in that territory. Before his death, I knew little about the Mapuche people, as did much of society.

Photographer documents five years of Mapuche struggle for survival in Chile

When Camilo Catillanca was killed, I eagerly shifted my focus from Rio Turbio in Argentina to southern Chile, undertaking seven or eight trips over four years. This project became one of the most challenging I have ever faced. Unlike typical journalism assignments where I returned with tangible results, this experience differed. The area remained under constant siege, which made it difficult for me to use my camera. Many “peñis” [brothers in the Mapuzundung language] faced continuous prosecution, and my presence as a “huinca” [white man] threatened their safety.

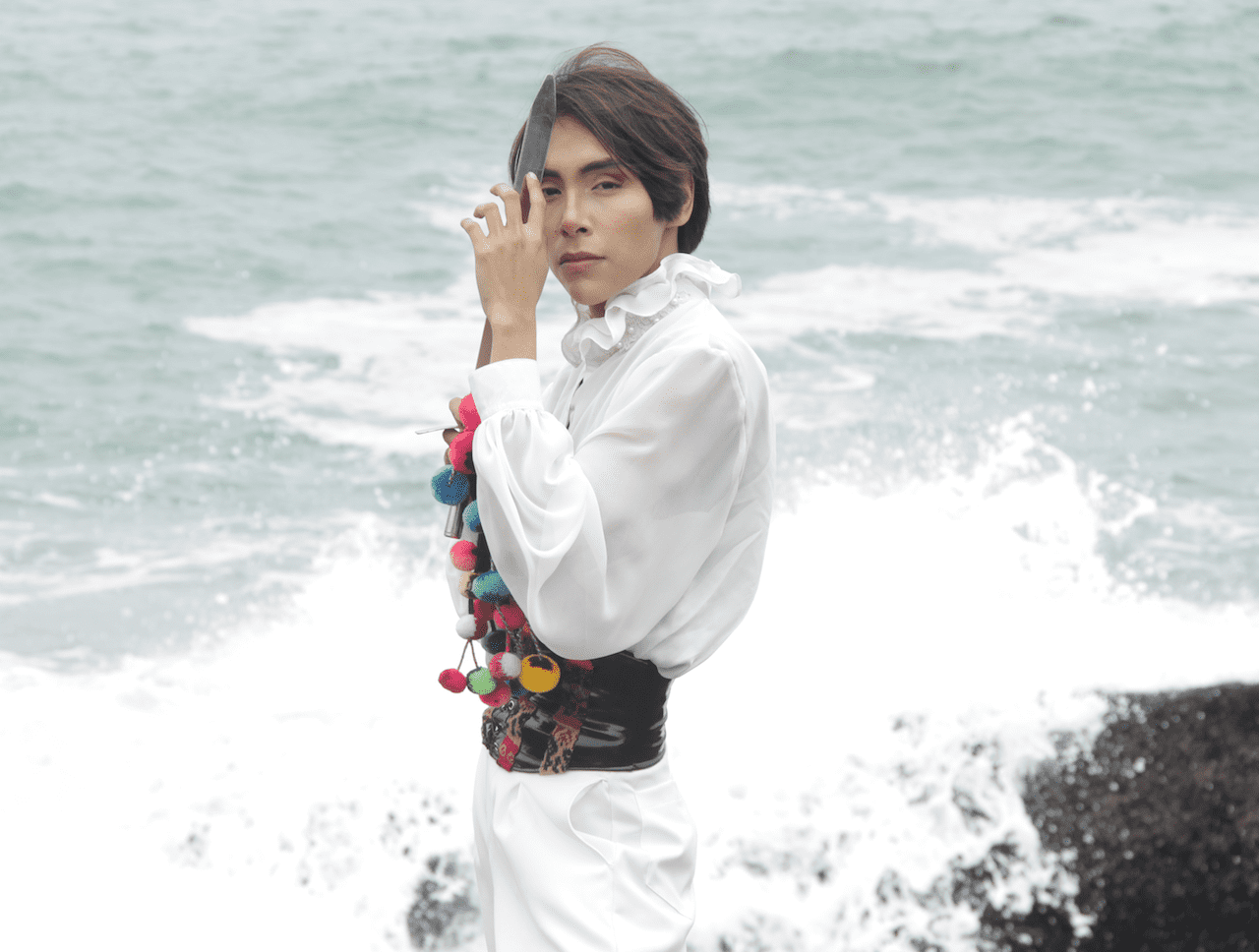

With a grant for visual storytellers from National Geographic and an award from the German magazine Geo, I spent the last five years working closely with the inhabitants of Roble Carimallin, Temucuicui, Butaco, and other smaller communities in Chile. At first, I arrived like a spy, weaving contacts and gradually earning trust. To understand the situation, I engaged in extensive conversations. Over time, my camera became a tool to document their resilience and resurgence.

I captured the community’s daily life amid the ongoing resistance. In the streets, confrontations erupted between police, armed with tanks and advanced weaponry, and the Mapuche people, who defended themselves with sticks and stones. These areas often remained under siege as communities fought to reclaim their ancestral lands, ceremonies, language, and culture. Witnessing this struggle profoundly transformed me.

During my stay in Chile, the community members generously provided me with lodging, food, friendship, and a sense of brotherhood. This experience deeply affected my perspective, revealing a different understanding and spiritual worldview. I learned that their social structure and cosmovision are rooted in the principle that when one falls, another rises. Moreover, they have no single leader. So, they continue to stand, live, and resist, as there is no head to cut off. This journey created one of my most significant documentary photography works.

Collective wisdom, healing practices, and spiritual depth of Machi Millaray Huichalaf

Each Mapuche community has a Lonko [chief of several Mapuche communities] who represents them. The community makes decisions collectively in assemblies held around a tree. This practice fosters resilience within the community, which proves crucial during widespread destruction. It encourages a reevaluation of the kind of life necessary to ensure the survival of the human species, particularly as large corporations leave seemingly irreversible impacts.

In my early years working with the territorial resistance in Araucanía, I traveled further south and met Machi Millaray Huichalaf, a spiritual leader and medicine woman. Authorities persecuted her for defending the Pilmaiquén River, sacred to the Mapuche people, and for promoting the awakening of her community.

The Machi, similar to a rural doctor, heals using ancestral plant knowledge. Her home sees long lines of both Mapuche and non-Mapuche patients with serious health issues. Over the years, I watched many people leave cured, which feels almost poetic in today’s world. She demonstrates that healing is possible with understanding.

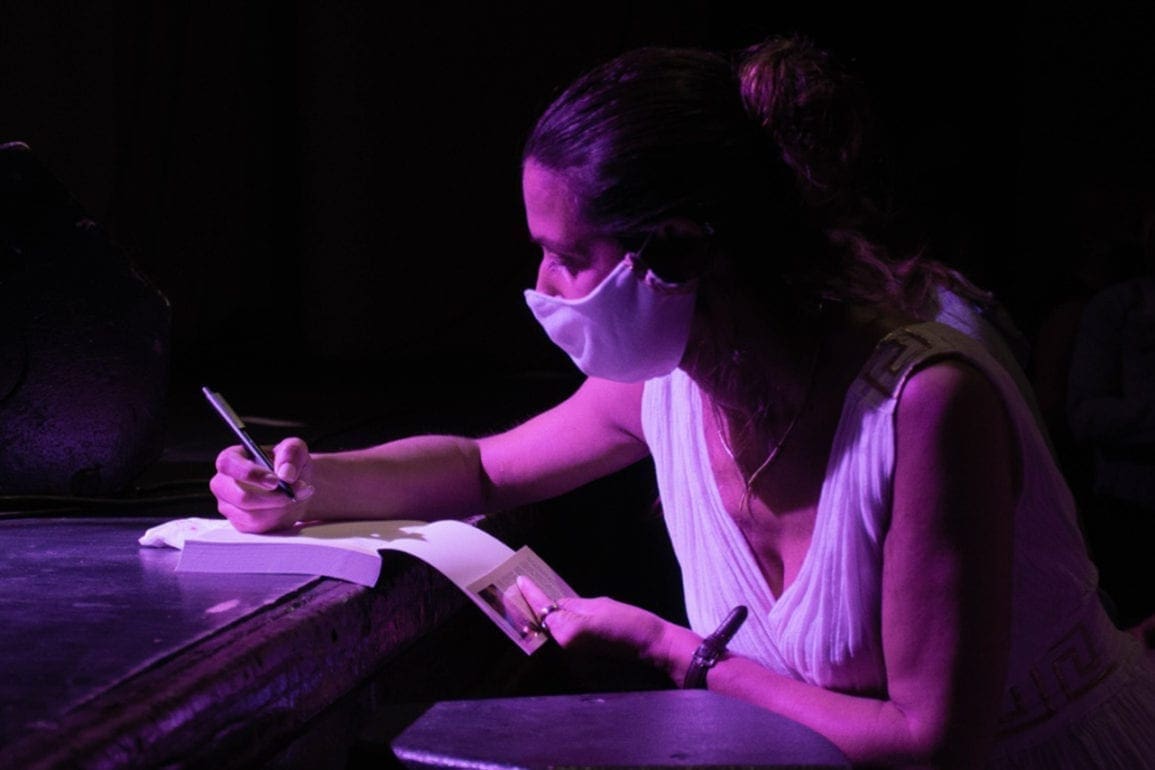

Throughout my project, I document their daily lives, healing practices, and ancient ceremonies where they communicate with the pulongos [spirits] to reconnect with their roots. However, I often fail to capture the most powerful images on camera, as I do not always receive permission to photograph them. Despite this, I have had the privilege of participating in and keeping vigil during many nights. I witnessed incredible beauty that I can only capture at certain moments, such as the first rays of sunlight in the morning.

Photographer captures sacred ceremonies and the resilient spirit of the community

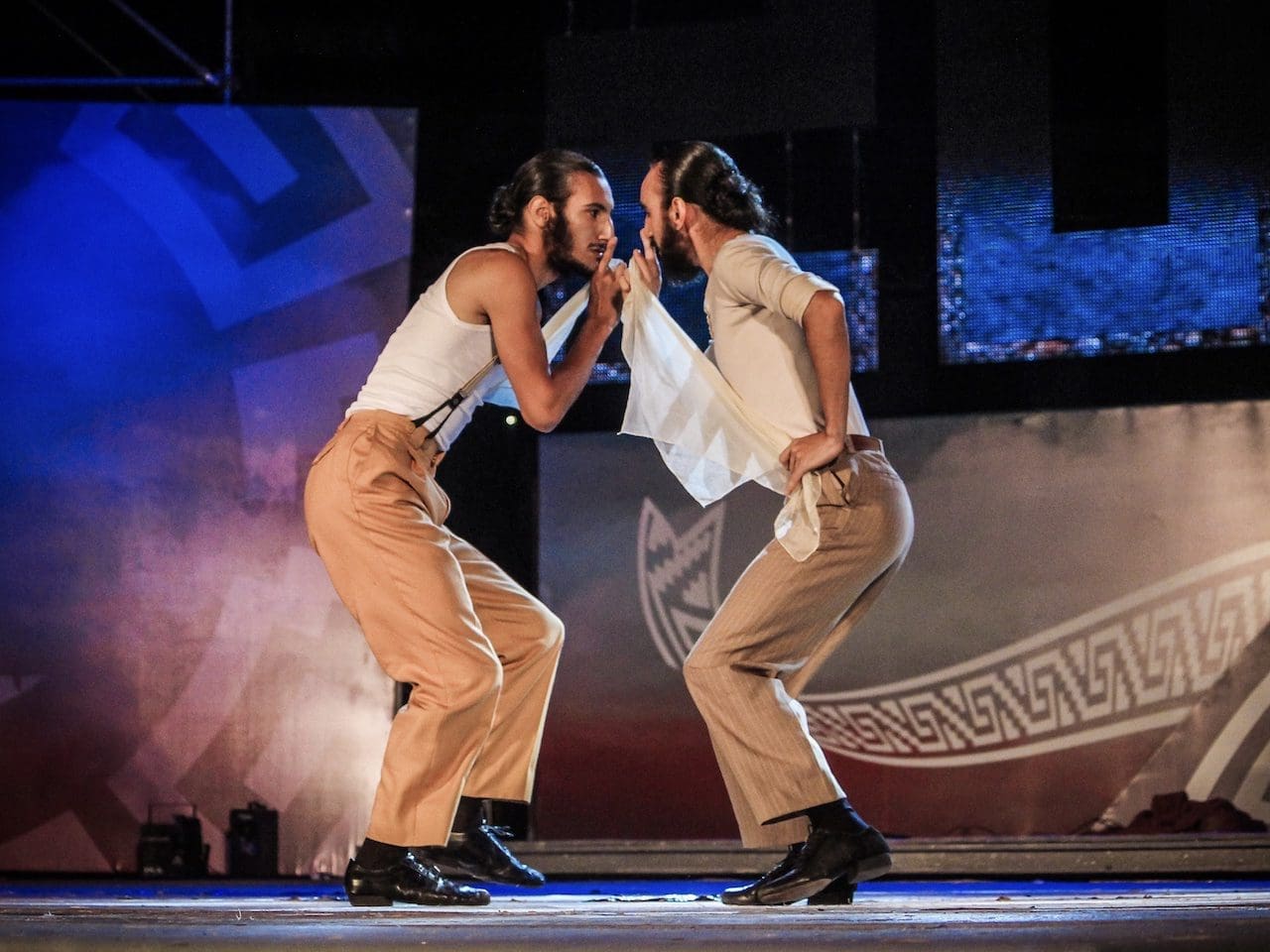

In the ceremonies I captured, Machi enters a trance, and the entire village performs sacred movements to connect with the energies of ancient spirits. The images convey a unique language, indescribable in words. Narrating them falls short and diminishes their essence. When approached with dignity and depth, only photography gives you real exposure to this majestic moment, inspiring profound transformation.

Amid the adventurous journey, my work reveals resilient people who continuously rise. They build sacred relationships with water and land. They engage with these elements and serve as the first line of resistance. Today, native peoples protect the land from destruction and play a crucial role in preserving life.

The photographs, sustained over time, form a cohesive body that threads together to narrate a story. Each image demands its place, connecting with others to create a unified narrative. In each face I portray, traces of suffering emerge. They uphold a spirituality tied to their territory, navigating a duality: one for the huinca world and another for their ancestral heritage. Undoubtedly, these people intertwine with dreams, nature, and instincts, guided by their ancestors.

Photographer wins 2024 World Press photo for documenting the Mapuche People

For over five years, I have journeyed through Mapuche communities on both sides of the Andes Mountains in Argentina and Chile. In my work titled “Mapuche, the Return of the Ancient Voices,” I capture the daily and profound aspects of the cultural, territorial, and spiritual recovery of the Mapuche people, one of the oldest populations in Latin America. As a result of this project, I won the prestigious World Press Photo 2024 photo contest for long-term projects in South America.

The Andes Mountains play a profound role in acting as a conduit of connection between regions that later divided into state boundaries. This mountain range, one of the world’s most significant, reveals its diverse beauty throughout the seasons. During winter, I saw the Andes blanketed in snow. Then, as the seasons changed, I observed its rocky and verdant charm in summer.

I watched as it bathed in morning light and glowed with oranges and reds in the afternoon. Every evening, I noticed it becoming enveloped by the wind, moon, and stars at night. This stunning landscape, dotted with lakes, consistently brings me back to the same people: the Mapuche. Telling this story inspires me greatly.

I witnessed these people, who are so alert and determined to fight for what is rightfully theirs. They ask for nothing and have shed their fears. In addition, the native peoples, with their deep understanding and relationship with nature, have always guarded it and continue to do so. They embody a profound consciousness that ensures the continuity of life, which resonates deeply with my work.