Airplane crash survivor featured in Oscar-nominated “Society of the Snow” on Netflix tells it in his words

From a Catholic perspective, we considered the soul and the body, and we reasoned that the two are separate. The body is simply water and mineral salts. We naturalized the prospect of eating people. Though careful at first, we soon got used to it.

- 2 years ago

April 3, 2024

LOS ANDES, Chile ꟷ Before boarding the airplane on that fateful day in 1972, I felt like a spoiled, good-for-nothing kid. My babysitter packed my suitcase. I never saw a dead person in my life and came from a well-off family. My father, a painter, gave us everything and the mountain range where I grew up served me well.

As the airplane crossed the Andes Mountains, we passed through two gigantic air holes. We shouted “O-lay” like bullfighters unconscious of what would transpire. Then, suddenly, we felt the blow. At 400 kilometers per hour, our airplane crashed into the mountain. The plane broke in the middle and ran like a sled with such luck, we never touched a rock. If the fuselage had hit stone, it would have broken us into pieces.

Read more stories from entertainers on Netflix at Orato World Media.

Young man and his four friends survive a plane crash in the Andes Mountains

On the airplane, as the disaster unfolded, the cold set in. Everyone screamed and the chaos felt absolute. I wanted to pray, thinking, “I’m going to start with the Our Father.” Then I thought, “No, it’s too long, I’m not going to finish it.” Instead, I turned to Gloria – the shortest Christian prayer I could think of. I then prayed the Hail Mary, which is mid-length. I said to myself, “I’ll kill two birds with one stone because my prayers are good with God and with the Virgin.” Though not very Catholic, I clung to God in those mountains.

Those in line to us – the pilot, co-pilot, and others – all died. A mommy’s boy, I said to Canessa in the middle of the mess, “Is this what you call a disaster?” I genuinely did not know the definition of the word; I was so naive.

The first days we survived in the Andes, I boasted about the fact that me and my four close friends lived. What’s more, I wrote to my mother on October 23, 10 days later. I said, “Luckily we are alive.” When two of my friends eventually died in an avalanche, I did not cry. As a human being, I found myself fighting for my life far from civilization. I mourned them later, when we returned home.

Something rarely talked about is the height where we crashed. When I returned to the site in the Andes later in life with a Discovery Channel producer, I witnessed it. At 4,200 meters you face serious trouble. You have to go lower, but we had no time to deal with that issue; we faced other problems.

Days pass and the survivors take things into their own hands

In the horrible cold, we hugged and hugged each other. A glass of water would have felt like gold. It remains impossible for snow to melt at 25 degrees below zero, so we invented silver cans. When the sun rose, we used the cans and drops of water began to fall. The thirst hits you more than the hunger. That thirst felt desperate.

In 10 days, 26 of us shared a can of seafood, two squares of chocolate I found, and some glasses of cherries. A military plane, it had zero food. By then, airplanes passed above us and we wanted to know where they searched. We felt convinced they saw us.

The person in charge of listening to the radio, Gustavo Nicolich, came in and told me, “Carlitos, I have good news to give you.” “What happened, Gustavo,” I asked. “I just listened to the Chilean radio where the announcer said that they ended the search for the Uruguayan plane.” I wanted to kill him and shouted, “Good news, you son of a bitch!”

He looked me in the eyes and said, “Do you know why this is good news? Because now we depend on ourselves and not on people outside. Carlitos‚ we have to find our resources.” Looking back, I can say Nicolich was right, because that day we stopped waiting, and started acting. We fought for our own story and went looking.

Desperately hungry: “Carlitos, I eat the pilot”

In life, we all experience the kind of hunger which makes you want to eat a sandwich. That constitutes initial hunger. Next comes a hunger making your stomach hurt. The walls of your stomach seem to stick together, and it gets in your head. Suddenly you know, if you do not eat, you will die.

[When the hunger set in] everyone had the same thought, but no one dared speak it – least of which me, the youngest amongst the group. I think Nando Parrado mentioned the idea first. He ventured toward the tail of the plane, and I told him, “Nando, there is nothing left in the pantry.” [The pantry was a woman’s bag where we found the seafood.] Nando looked at me and said, “Carlitos, I eat the pilot.”

Perhaps the comment came naturally. Nando lost his mother in the crash and his sister five days later. He was the most distant of us all. That day, we took a short expedition and I remember staying away from Adolfo Strauch thinking, “I’m not going to eat my best friend.” I decided to ask what the others thought and brought it up. Then, I quickly blamed Nando. “He’s completely crazy,” I said, “he wants to eat the pilot.”

Adolfo looked at me and said, “No Carlitos, he’s not that crazy. My cousins and I already thought about it.” Everyone did, though no one dared to speak. When we got back, the group discussed it with no resistance. It felt simple. We were starving; no one looked for us; and we possessed the most sacred of rights – to live and to get back home.

Buried by an avalanche

We made a solemn pact: if any of us died, we would be at the disposal of the others. We trusted the first-year medical students on board who survived with us. Eating would give us the energy to find our way out. If we did not eat, our escape would be impossible.

The discussion took an almost philosophical tone at first. We compared our discussion to requiring consent for organ donation. From a Catholic perspective, we considered the soul and the body, and we reasoned that the two are separate. The body is simply water and mineral salts. We naturalized the prospect of eating people. Though careful at first, we soon got used to it.

Then came the avalanche that buried us for three days. I turned 19 there, under the snow. My childishness made me want to celebrate my birthday in the midst of chaos. Like the character in Life is Beautiful, I maintained humor throughout the drama.

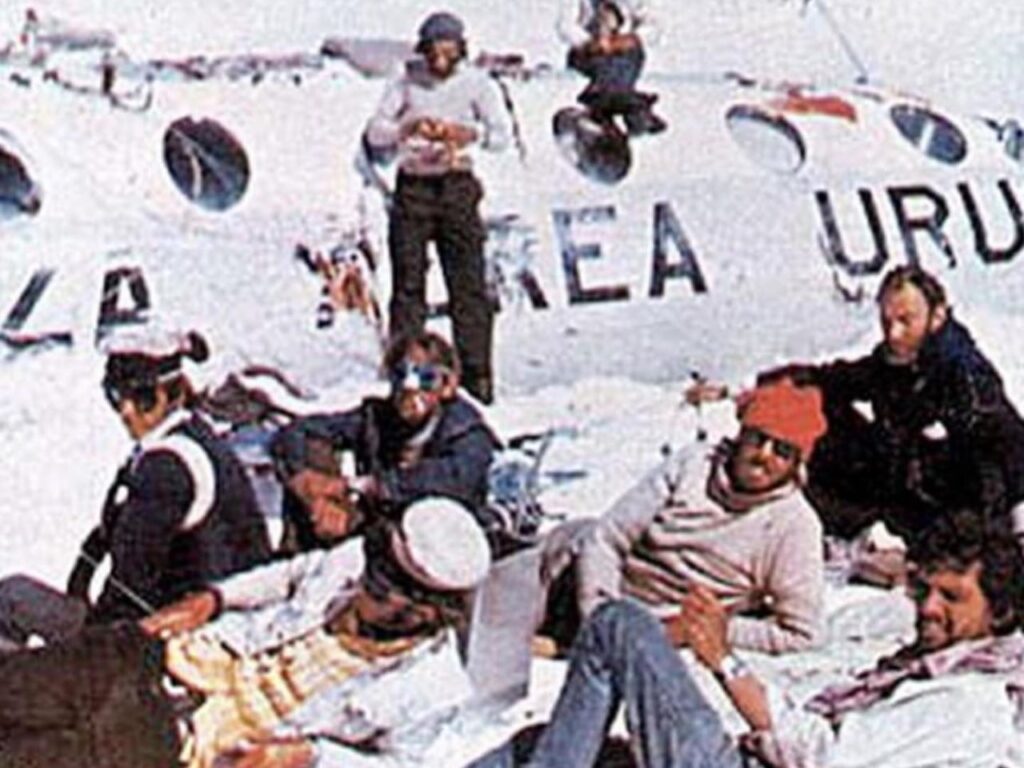

Through the ordeal, we took photos on only one day. We did not want to photograph the unfolding disaster. In one of the photos you see a shirtless boy which is me. I remember saying, “I want to get to Punta del Este with a tan.” Perhaps I displayed an act of frivolity, or perhaps an act of hope. At one point I gave over my Pierre Cardin jacket – a gift from my dad – so Canessa could cover his legs. It hurt to see the jacket torn. After all, I wanted to show it off in Chile.

Two survivors walk away and 10 days pass

I though a lot about my mom and during in the Andes. My mother had a Fiat 850, a European car that came without seatbelts, so I stole three from the airplane to take home to her. I could have grabbed something more intelligent – a compass or a barometer – but the seatbelts felt like a symbol. It linked me to my mom and that became the most important thing.

Still, at some point, we stopped thinking about family. It soon felt like another burden. My obsession to transcend the situation became incredible. Simultaneously, absurd thoughts about death arose. If I died, I thought, I want them to think I died in the crash, so I shaved my beard to look like it never grew.

I don’t know what felt harder – the waiting or the walking. Days passed and nothing happened. Two of the survivors, Fernando Parrado and Roberto Canesa, left to walk. It had been 70 days since the accident and 10 days of Fernando and Roberto’s departure, I cried in despair, hugging Coche Iniciarte. The crying turned desperate. We previously set an arbitrary deadline to be home by Christmas. Now the holiday loomed around the corner.

By some psychological mechanism, my depression and anguish abruptly shifted to euphoria when I experienced a premonition. Fernando and Roberto made it, I thought, but I told no one. The next day, Daniel Fernández awoke and said, “Carlitos, I just dreamed that Fernando and Roberto arrived somewhere.” I confirmed his feeling, and we turned on the radio.

“Hello, guys, I am sending you a helicopter as a Christmas gift.”

In the middle of static we heard the words, “Uruguayan plane.” Switching the dial, we heard Uruguayan ambassador César Charlone at the Pudahuel airport say, “Gentlemen, I must say that it is official that Fernando Parrado and Roberto Canessa have appeared.” Hearing their names felt like the end of our pain and anguish. We stopped crying at the prospect of our freedom.

We hugged and celebrated, looking quite crazy around that little device lying in the snow. The radio mentioned a helicopter, so I combed by hair with gel and packed the seatbelts in my suitcase. Then, we sat down to wait.

It felt like a long wait when suddenly, we felt the helicopter in the distance and heard the wonderful noise of blades far away. I wonder what it was like for the pilots to see us when they burst into the valley. Three members of the Socorro Andino Chileno corps emerged. One of them, Sergio Díaz, shouted my name. “I have two letters for you,” he said. The first letter said, “Dear Carlitos Miguel, As you see I never failed you. I waited for you with more faith in God than ever. Your mother is just arriving in Chile now. A hug, the old man.”

The second letter looked prettier than the first with a helicopter drawn on it. It said, “Hello, guys, I am sending you a helicopter as a Christmas gift.” That day was December 22.

Society of the Snow survivor gets sober: “I learned, the world keeps on moving.”

In the aftermath, fame tripped me up. It feels very attractive to be famous. Anyone who says otherwise is lying. We appeared on the cover of Gente and that summer of 1972, everyone talked about us. Without even noticing, I started drinking alcohol. I got involved with and entered a world of drugs and booze. When it became too much I asked myself, “After having fought so hard for life, how can I get involved in this deathly project?” I joined Narcotics Anonymous and have 34 years of sobriety today.

I returned to the crash site three times. First with 11 other survivors, then the Discovery Channel, and finally with my two children, four grandchildren, and about 100 other people. With the survivors, I used humor and made them laugh; but I couldn’t clown around when my children came.

That time, I really saw the suffering that took place in those mountains. I recently learned a wonderful phrase from Saint Franics of Assisi: “Begin by doing what is necessary, then what is possible, and you will find yourself doing the impossible.” That’s exactly what we did.

I see the crash as neither a tragedy nor a miracle.AI miracle would be everyone surviving. Some did die tragically, while others triumphed. I focus on the positive side. Today, those young people who survived have multiplied. I have eight children and grandchildren. On December 22, on the 50th anniversary, the survivors boasted 120 descendants in total.

I wrote a book called “After the 10th.” The world kept turning as we grappled with the freezing cold, surviving in the Andes. People played soccer. Montevideo hosted Beach Day. The astronauts reached the moon, and our airplane crashed. This simple truth can be a brutal blow to human arrogance. We think when something happens to us, the world stops.

I learned, the world keeps on moving.