After October 7, life in Gaza becomes more sinister for Palestinian doctor and his family

The high-pitched whistling and booming sounds grew closer and closer. On the third floor, we felt the ground begin to shake. Unable to stand on our feet, we stumbled and fell as we attempted to get to safety. Crawling closer, my family hugged each other, hoping to protect ourselves with our arms.

- 2 years ago

July 13, 2024

KHAN YUNIS, Gaza ꟷ After living in Bolivia and Argentina for a time, I returned to my birthplace in Palestine 12 years ago. I obtained a job at a state hospital as a physician. While I only intended to stay in Gaza for a few months, I soon discovered the government was withholding almost 70 percent of my pay. While they promised to return it, that never happened. I could barely afford the basics, let alone build up the money to leave Gaza.

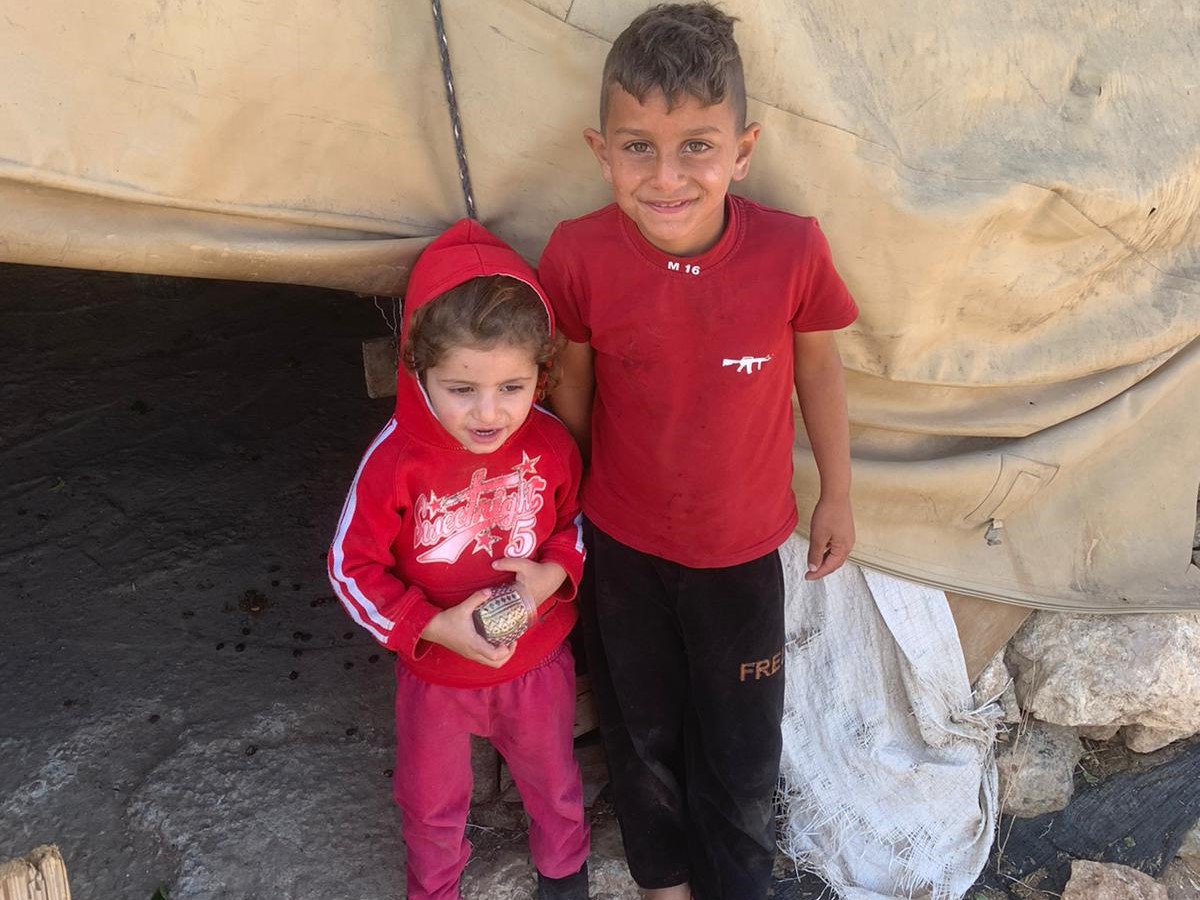

Stranded at the border, I resigned myself to staying. In that chaotic atmosphere, I met my wife, fell in love, and had five children. War came and went, and I lived through five major conflicts. As the climate became more terrifying, fear pervaded the streets. A sense of helplessness grew, with few getting out. I felt trapped in a sea of violence.

After October 7, 2023, with the outbreak of war [between Hamas and Israel], everything became more extreme and sinister. My $200/week salary provided only enough for my family to survive for one week before the war. With each passing day, our economic situation worsened. Prices began to increase and supplies dwindled. What once cost $1 now cost 10 or 20 times more. With borders closed, it felt like standing at an abyss – impossible to get out, but unable to pay for basic things. I felt like we would either die from bombs or starvation.

Read more stories from both sides of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict at Orato World Media.

We needed to get out of Gaza: instead, the neighborhood became a war zone

My wife and I always dreamed of a life where our children no longer suffered the danger of guns or the screams of terror. Yet, we felt we had no future. Living conditions in Palestine have always been deplorable. The basic needs of the people are not met. Even before the war, electricity came every six to eight hours. Procuring drinking water, at times, felt like a titanic task.

After October 7, however, the environment significantly worsened. After two weeks of focused attacks on northern Gaza, Israel initiated targeted attacks inside the neighborhood where we lived. One of those attacks hit my building.

The high-pitched whistling and booming sounds grew closer and closer. On the third floor, we felt the ground begin to shake. Unable to stand on our feet, we stumbled and fell as we attempted to get to safety. Crawling closer, my family hugged each other, hoping to protect ourselves with our arms.

When we felt the floor stabilize, I wiped the tears from my children’s faces and calmed them down. Walking down the stairs, we looked to see where the attack took place. My heart pounded and my hands became sweaty. I feared another attack at any moment. Every step felt bewildering, uncertain what might happen next, but getting out of there was our only option.

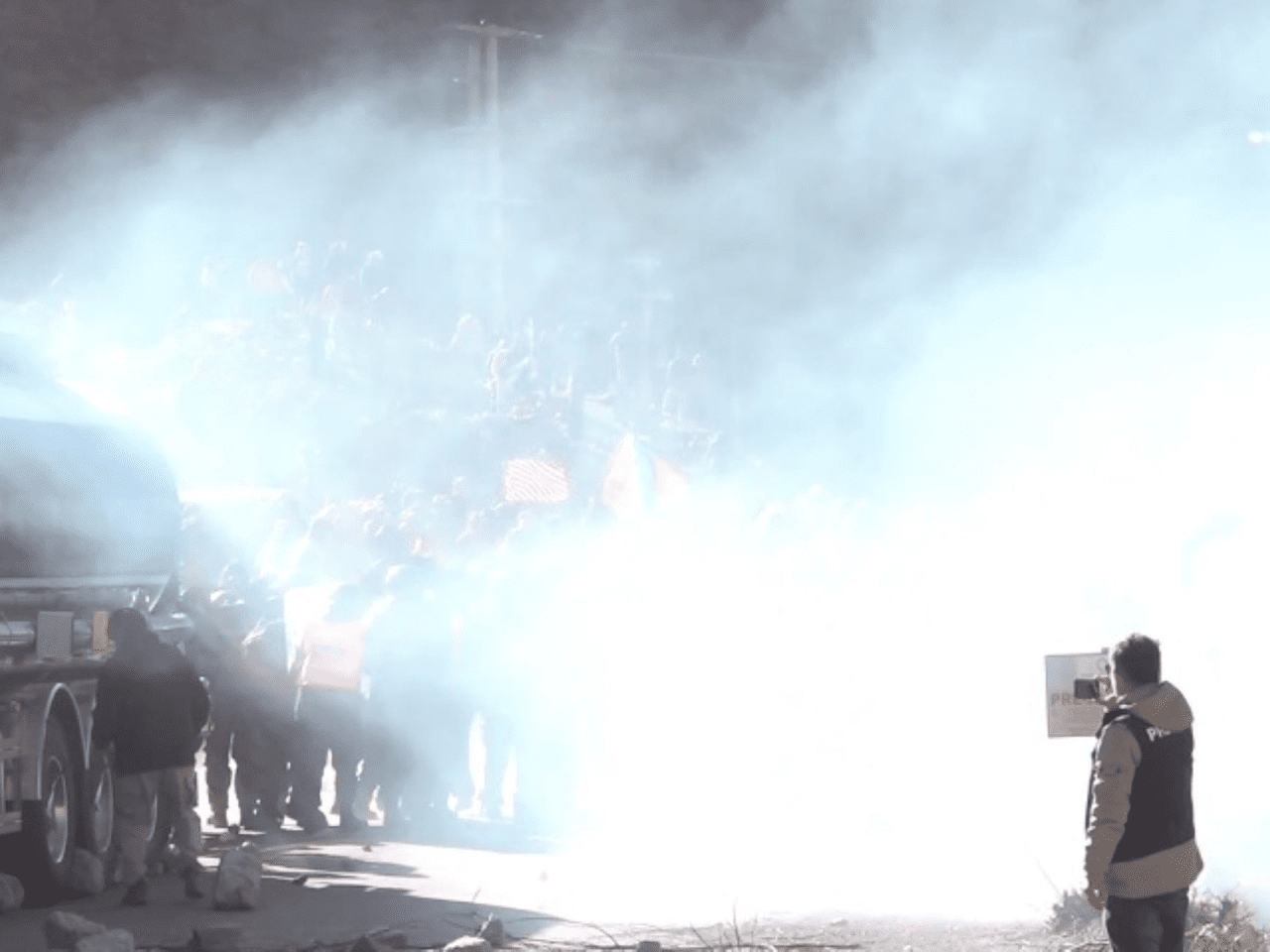

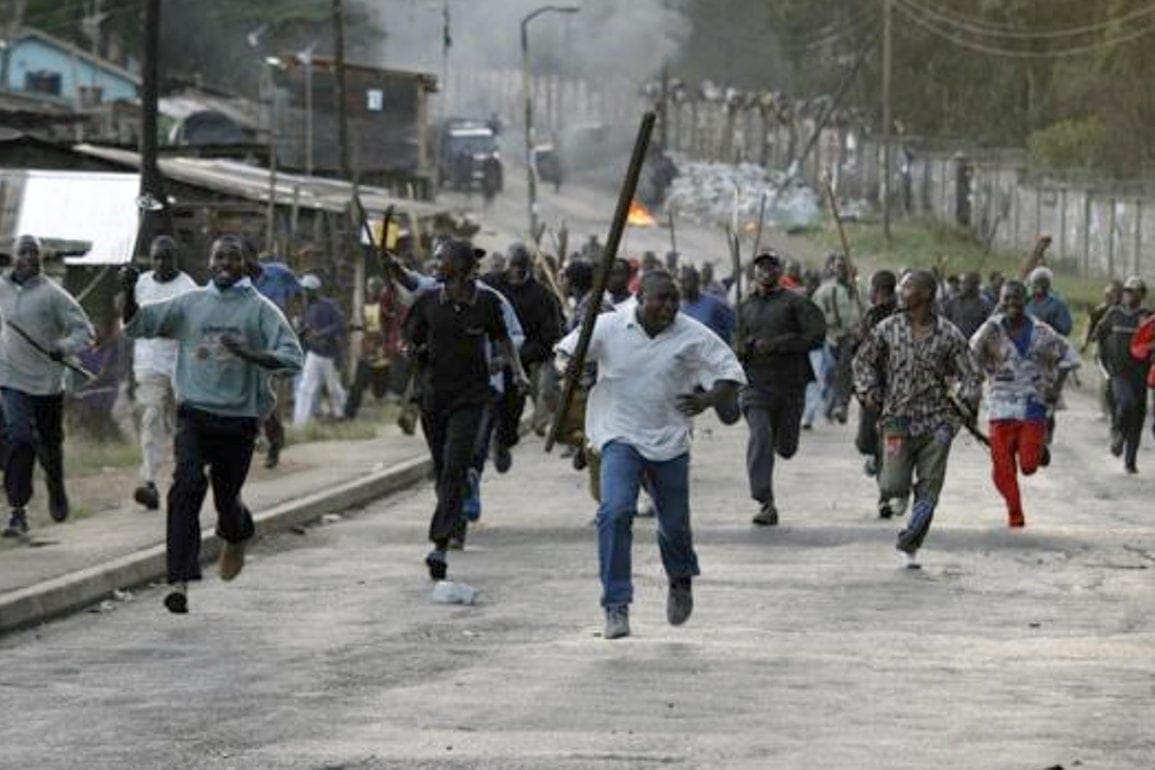

As soon as I reached the bottom of the stairs, I saw people running panicked from the buildings. They abandoned their homes for fear of dying. I looked up to see burned out areas billowing with smoke and huge flames. Injured people lay everywhere crying in pain and anguish. Tears streamed down my face.

Missiles crumbled buildings and a woman evaporated in a cloud of dust

My family and I waited where we could. After a few hours, the fire brigade and ambulance arrived. Medical rescuers began removing bodies of all ages from the ground, splattered with dirt and blood. I told my children not to look at the brutal sight.

When the fires dissipated, we returned to our home. Sleeping there that night was the most terrifying moment I ever experienced. The only thing I felt certain of was that things were going to get worse. The attacks increased and people began leaving the neighborhood in fear. It became a deserted and desolate ghost land.

We stayed, and about five months ago, things escalated. While we saw multiple attacks take place, one stands out. A group of people broke into my flat in the early hours of the morning. They attempted to drag us out by force while threatening us with guns, pointing them directly at our bodies. In total despair, I thought only of my family. “I’m an emergency doctor,” I pleaded, trembling. On my knees, I begged for mercy, and the men finally left.

Less than a week later, seven buildings in the area crumbled to the ground from missile strikes as I watched from my window. My family and I saw a woman, trying to escape through the square, when she blew up in a cloud of dust. That day become decisive: we needed to leave our home.

My brother-in-law gave us a few minutes to ready ourselves before picking us up. Amidst intense commotion, we tried to stay calm, gathering important papers and basic clothes. At the front door we waited for a few moments, got into the car, and escaped. I felt fear the entire time.

Doctor waits in long lines for supplies, fears for family’s safety in Gaza

As we made our way to safety, for religious reasons, my wife and I had to separate. I am not a follower of Islam, so according to custom in my wife’s family, I could not stay at the house where she would be staying. One of my sons and I traveled 10 kilometers to Khan Yunis near Rafah, while my wife and four other children went three kilometers to her sister’s house.

Uncertain we would see each other again, the sad farewell left me anguished. My chest ached thinking something could happen to them in my absence. I looked at my family, broken by violence, terror, and war.

Within a few weeks, east Khan Yunis destabilized so my son and I fled further into Rafah. Every day there, I saw death and hell on the faces of the people. It seemed I saw 15 to 30 people die every day. Still able to travel, every 10 days, I saw my wife and daughters, bringing them what little food I obtained. I stood in queues for hours at aid centers in the oppressive heat, exhausted.

Beads of sweat trickled down the weary faces of thousands of people awaiting an odd box of canned food, a few vegetables, some soap, and a couple rolls of toilet paper. Everything became scarce and miserable. Yet, day after day, I stood in that line hoping to have something to take to my family.

The shelter offered no services. Garbage went uncollected, sitting for days and days. We lived on dirt floors with barely a tank of drinking water available. When attacks happened near my wife and children, I kept in touch by phone. Hearing their voices was an indescribable feeling.

Life in Rafah deteriorated, family returns to Khan Yunis to find more devestation

Desperation, fear, and sadness haunted me in Rafah. Having to be constantly alert caused me panic, especially at night when bombs exploded and the earth trembled. The smoke grew closer, and I understood no safe place existed. While my son slept, I hid my face dejectedly in my hands and with my mouth closed, stifled a scream while I soaked my hands in tears.

I saw attacks on flats, buildings, motorbikes, cars, and even civilians. It seemed if someone looked suspicious, they were massacred, even if it was just scared women and children protecting their lives. I saw ambulances, police cars, city halls, and places dedicated to serving people blown up.

Power stations exploded in the air. Wires and poles lay on the ground as areas were left in rubble, dust, and ash. If the goal was chaos, that goal was achieved. As food, water, and electricity dwindled, I looked upon inhumane devastation.

Months passed and the invasion of Rafah reached an irreversible point, so my son and I found an opportunity to return to Khan Yunis. The neighborhood where we stayed before was declared a safe, conflict-free zone or a quiet area, according to Israel.

When we arrived with the whole family, a scene of utter destruction left us in shock. Dust permeated the air amidst destroyed buildings. People’s faces told stories of great pain and loss. We settled in, using car batteries to generate light. We charged our mobile phones at specific spots that had solar panels. Every morning, we embarked on a journey to fetch gallons of water, some to drink and some to bathe and wash our things.

Everywhere we looked, fighting continued. The sounds of shelling and the screams of victims echoed. Attacks could happen any time of day, but at night, it felt like the door to hell was opened.

Treating children in Gaza, I reach my limit as a doctor and a man

I began working as a doctor again in Khan Yunis. Passing through dangerous areas on my way to the hospital, I have narrowly escaped bombs. Once, on the way there, I smelled intense smoke. In the distance, I saw an almost-black cloud. The closer I got, I noticed it pouring out of a car, attacked just seconds before.

Inside, the corpses of burning bodies emanated a smell I can never forget. Suddenly, I could not swallow or breathe. Feeling nauseous, I looked down at the ground, only to see pieces of human beings scattered around the car. Others tried desperately to put the fire out while I went into shock.

Working in intensive care, I regularly encounter serious situations. However, cases involving children make me weak. Kids arrive seriously injured, missing limbs, and screaming in desperation. Crying and torn, most of them beg for their parents. At times, I must explain their parents died before arrival, and they fall apart in my arms.

I consider their future in Gaza, and it breaks my heart. All of us live the same way: in misery. We found a house while others live in fragile tents. At the refugee camps, chaos and starvation reign. Being in a house helps a little, but pieces of this old structure blow away while it retains enormous heat.

Others live here too. We take turns using the bathroom while daily chores and activities become a battle. Lack of gas leaves us at times cooking on a fire in the back of the house. During the day, we wash clothes and bathe. I work 24 hours and rest for 48. At work, I fetch water and charge my phone battery. This situation feels like living in a big prison. We cannot move, nothing is safe, and we are surrounded by fighting and danger. The IDF could advance at any moment if they wanted to. We feel terrified, with no way out.