Beirut hospitals overwhelmed as conflict escalates, civilians face widespread displacement and fear

Since late September, bombings have ravaged multiple regions, reaching Beirut. I vividly remember the day Hassan Nasrallah was killed. A brutal bombing leveled a densely populated neighborhood, with over 16 missiles reducing the area to rubble.

- 1 year ago

October 28, 2024

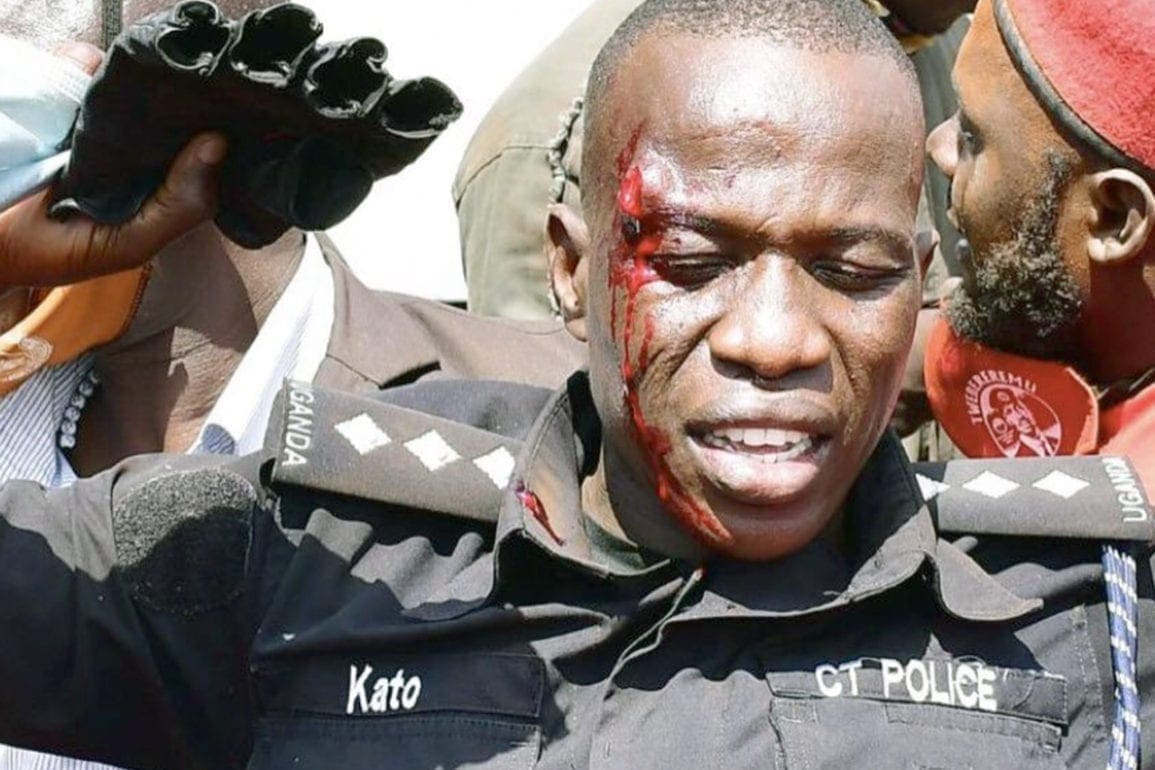

BEIRUT, Lebanon — The situation in Beirut’s hospitals quickly spiraled into chaos. At the American University of Beirut Medical Center where I work, victims flooded in, bloodied and severely wounded. We performed finger amputations, complex surgeries, and treated patients who lost their eyes due to exploding devices.

Today, we live in constant fear. The devastation in Gaza feels like a haunting preview of what may come. The uncertainty feels suffocating, like a surreal nightmare. Sadly, this becomes our reality, and we are left grappling with it every day.

Read more conflict stories at Orato World Media.

Lebanon’s cycle of conflict: war resurfacing

Growing up in Lebanon meant constant instability, with recurring conflicts and wars. Each summer, we visited my mother’s family in Spain, sometimes staying longer because we could not return home. One memory stands out. My parents sat under a colorful umbrella, listening to music. Suddenly, a news bulletin interrupted the tranquility. Beirut, where my father’s family lived, was bombed. My parents’ faces crumbled, and we felt overwhelmed with grief. That summer afternoon, under the umbrella, we hugged tightly, consumed by sorrow.

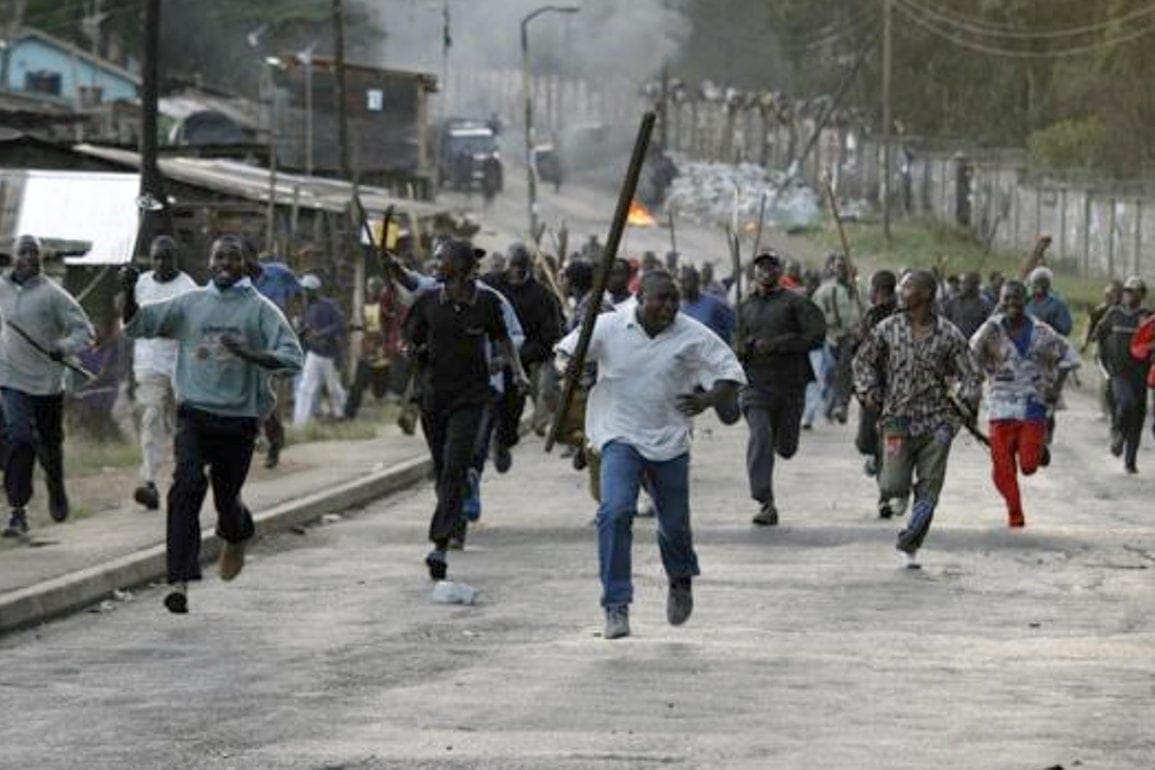

In 1982, the city became the epicenter of a brutal civil war. I vividly recall the bombs, smoke, and terror that engulfed our surroundings. This devastation returned in 2006, as Israel launched another intense offensive, targeting vital infrastructure and forcing civilians to flee. The streets fell into chaos, and families, like before, became displaced in waves.

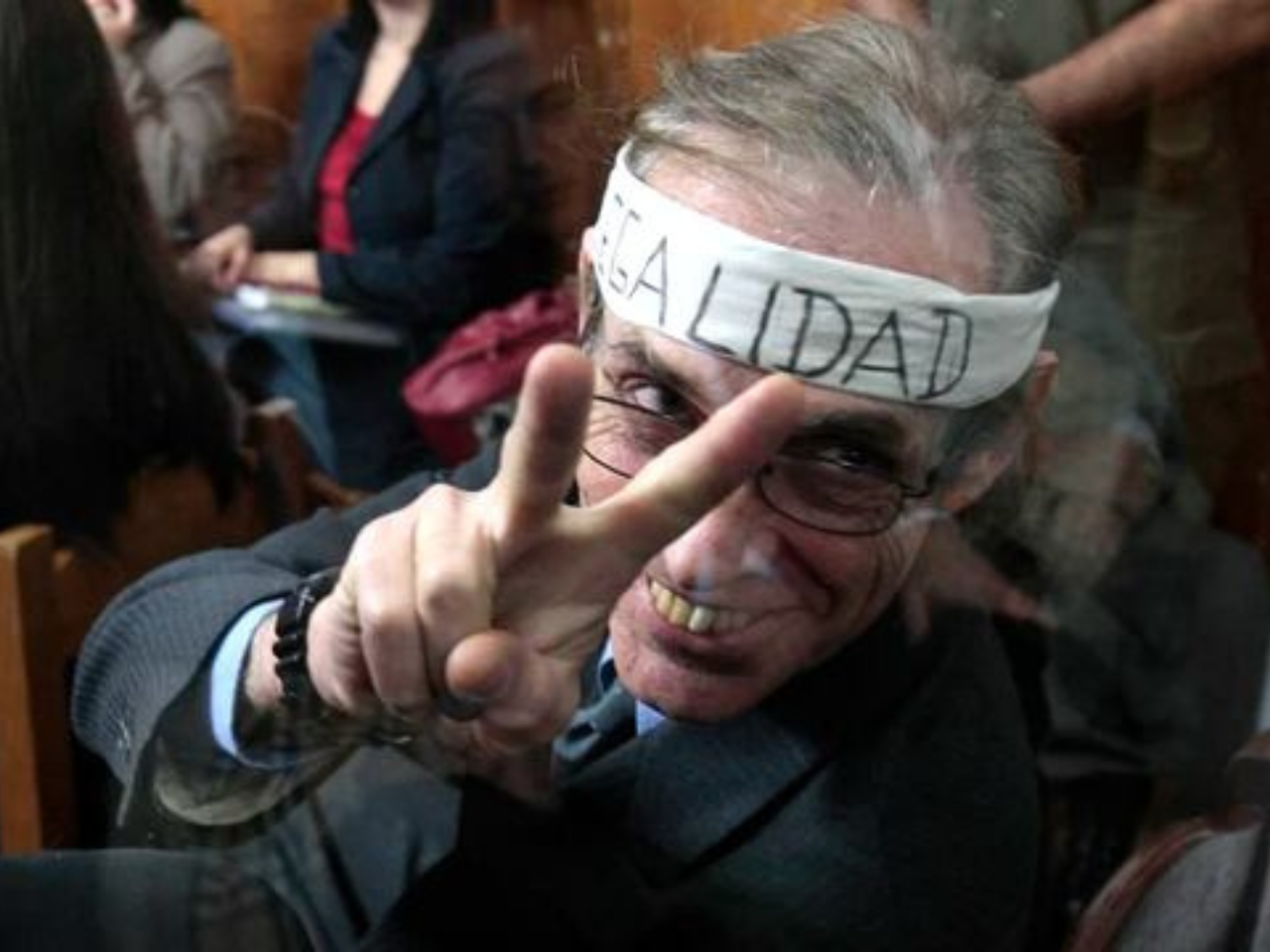

These experiences starkly highlight the contrast between moments of peace and the terror of war. One moment, we enjoyed a day at the beach; the next, sorrow and fear gripped us. The cycles of conflict, displacement, and uncertainty profoundly shape Lebanon and its people.

As a mother, I remember my daughters being terrified by the sounds of bombs, the thunderous noise, and the flashes in the sky. Despite my fear, I tried to comfort them. I told them it was thunder or fireworks, but their frightened faces showed me they knew better. The war left an indelible mark on all of us.

Panic spread like wildfire throughout Beirut

With great sadness, those same feelings of despair have returned. A 60-year-old patient tearfully told me she spent 50 years in war. Israel and Hezbollah appear to have crossed a threshold, and despite both claiming they do not want escalation, it is happening.

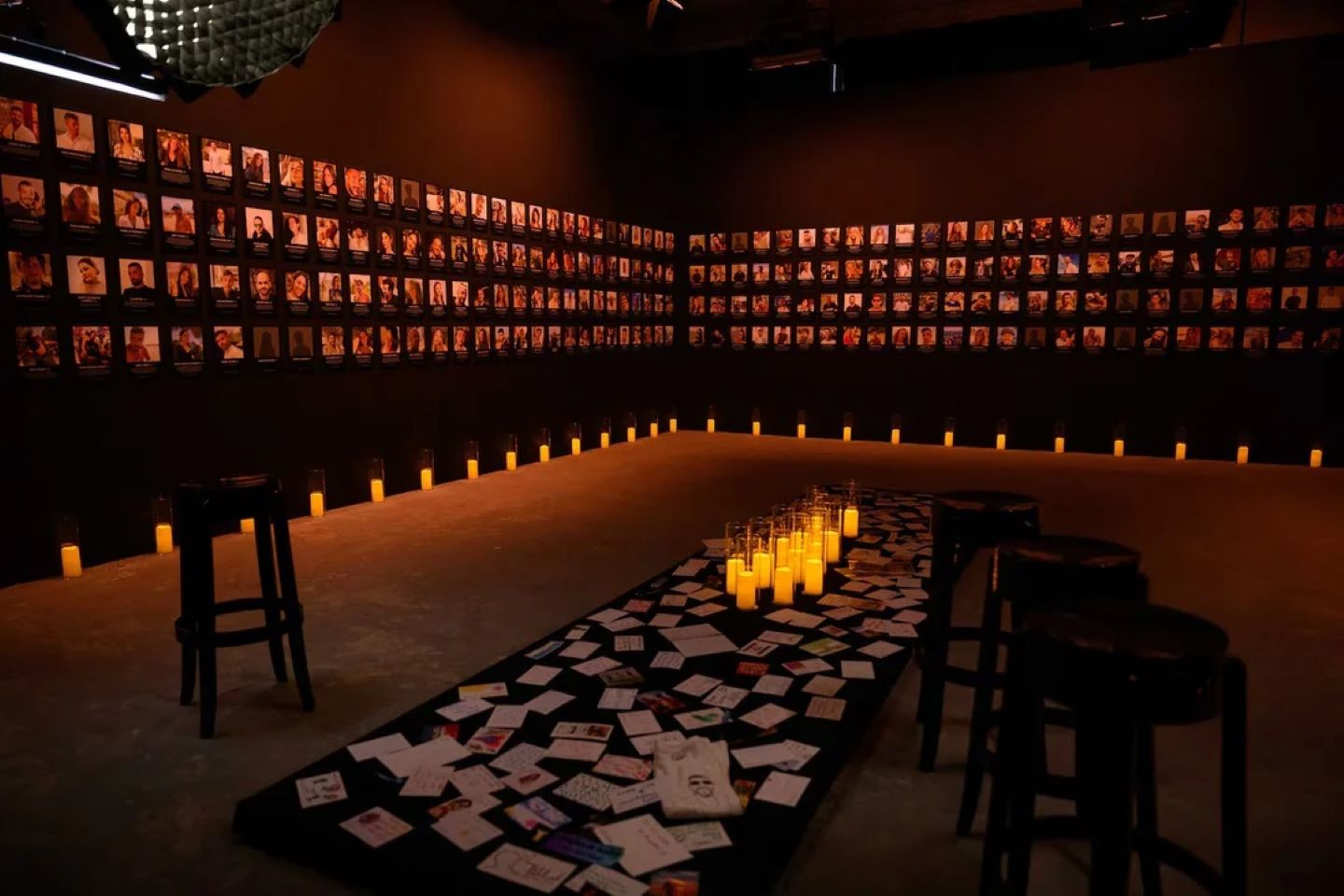

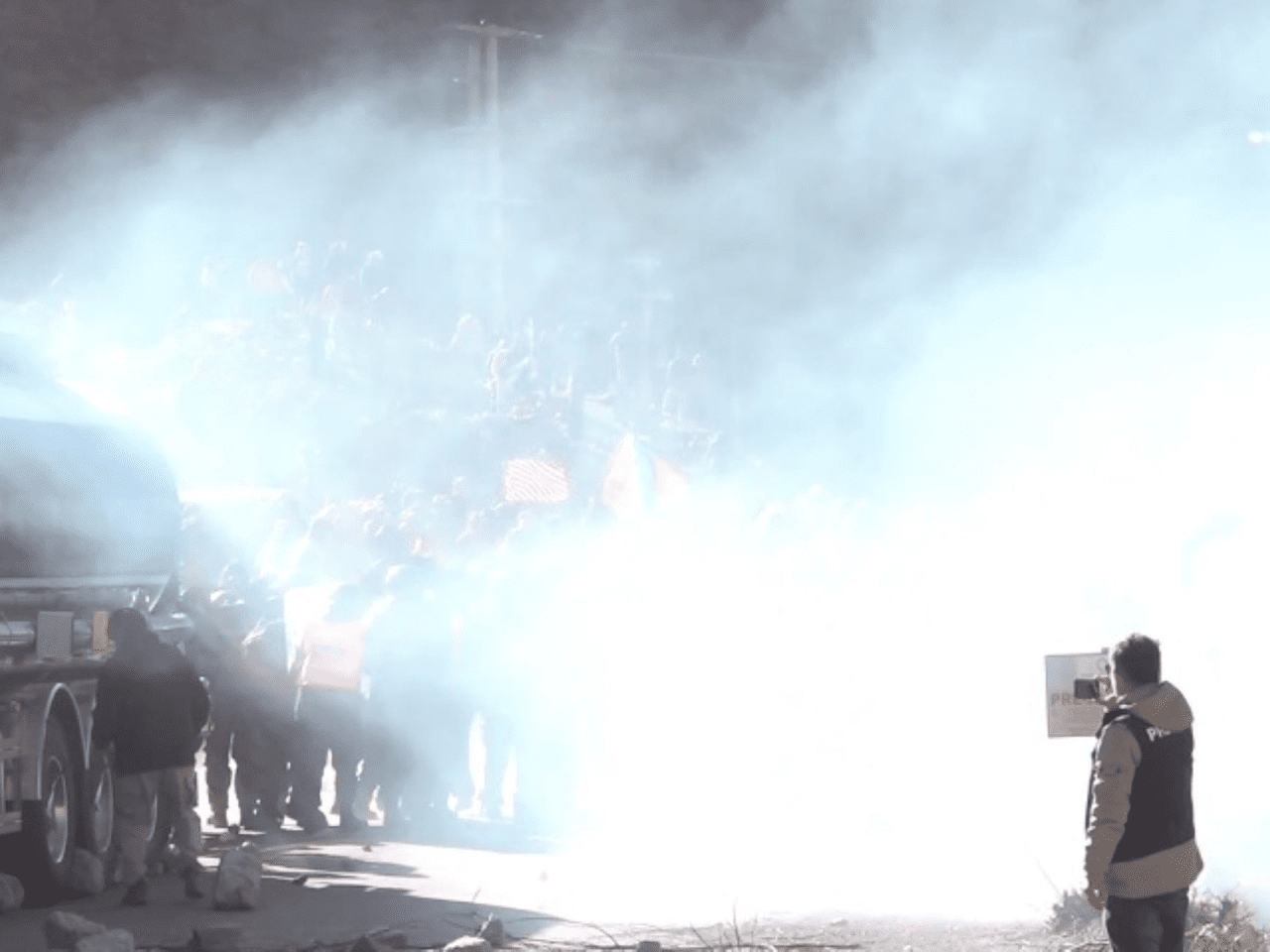

On September 17, chaos took over Beirut’s suburbs. Thousands of Hezbollah supporters received messages on their beepers, which exploded moments later. Walkie-talkies met the same fate the next day. Over 30 people died, and 3,000 were wounded, as panic spread like wildfire throughout the city. The situation at Beirut’s hospitals felt overwhelming. At the hospital where I work, victims arrived in waves. Some needed specialized surgeries for eye injuries and finger amputations because of the blasts.

One man told me, “My wife and I were just walking when something exploded. People were lying on the ground, and no one knew what was happening.” Sirens echoed across the city as ambulances navigated the chaotic streets. Outside the emergency room, crowds anxiously gathered for news. Meanwhile, in the southern suburbs, overwhelmed hospitals treated the wounded on mattresses in the parking lot.

Makeshift tents under a bridge sheltered victims as hundreds gathered to donate blood. The blaring sirens added to the tense atmosphere, amplifying the sense of chaos and fear. The violence that gripped Beirut that day served as a reminder to all of us. This country bears a profound scar from past wars, and it can easily reopen.

My life has drastically changed. Every day I feel fear.

The situation is spiraling deeper into conflict now. Civilians become displaced in numbers greater than anything I have seen before, with millions fleeing their homes in recent weeks. Since late September, bombings ravaged multiple regions, reaching Beirut. I vividly remember the day Hassan Nasrallah was killed. A brutal bombing leveled a densely populated neighborhood, with over 16 missiles reducing the area to rubble. I thought no one could survive.

The aftermath left me trembling, overwhelmed by the brutal irony. Wherever I am, as soon as I hear a bang, I freeze in shock, unable to react. I desperately try to figure out where it came from and who it affected. The uncertainty becomes paralyzing, and the constant threat makes it impossible to feel safe, as the next target could be me, my children, or my friends.

My life drastically changed. Every day I feel fear. I live one kilometer from Beirut’s southern suburbs, near the airport, where explosions echo through the night like rolling thunder. They only pause briefly before returning. Fighter planes fly overhead constantly, shaking everything like an earthquake. Drones hover endlessly, driving us to the brink of exhaustion. It feels impossible to escape the constant anxiety.

The nights become almost unbearable, and I sleep poorly. One of my daughters still lives with me and could no longer stand sleeping in our home. The bombings overwhelmed her every night, so now she stays with a friend 30 kilometers away, seeking peace. Constant fear, sleeplessness, and the dread that comes with every passing hour of conflict becomes our new reality.

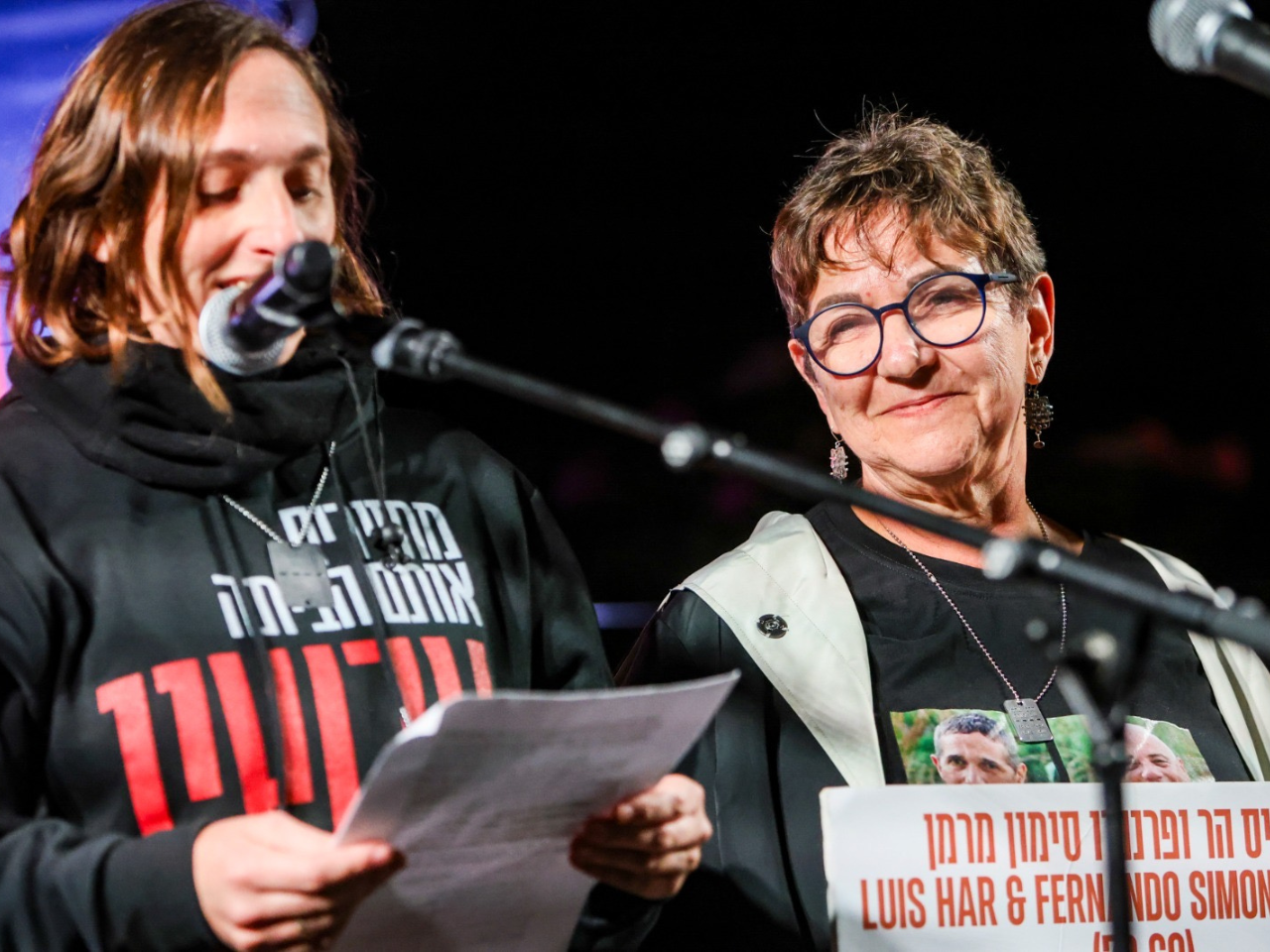

Thousands displaced: “Teams distribute medicine and aid, while others cook in communal spaces to provide food”

Entire families now take shelter in schools, hospitals, convents, and even nightclubs that opened their doors in solidarity. Where alcohol and music once flowed, now you see diapers and hear the cries of desperate people. Schools and universities remain closed, as parents fear sending their children into danger. Roads become clogged with people fleeing, while constant news coverage of the conflict fuels anxiety.

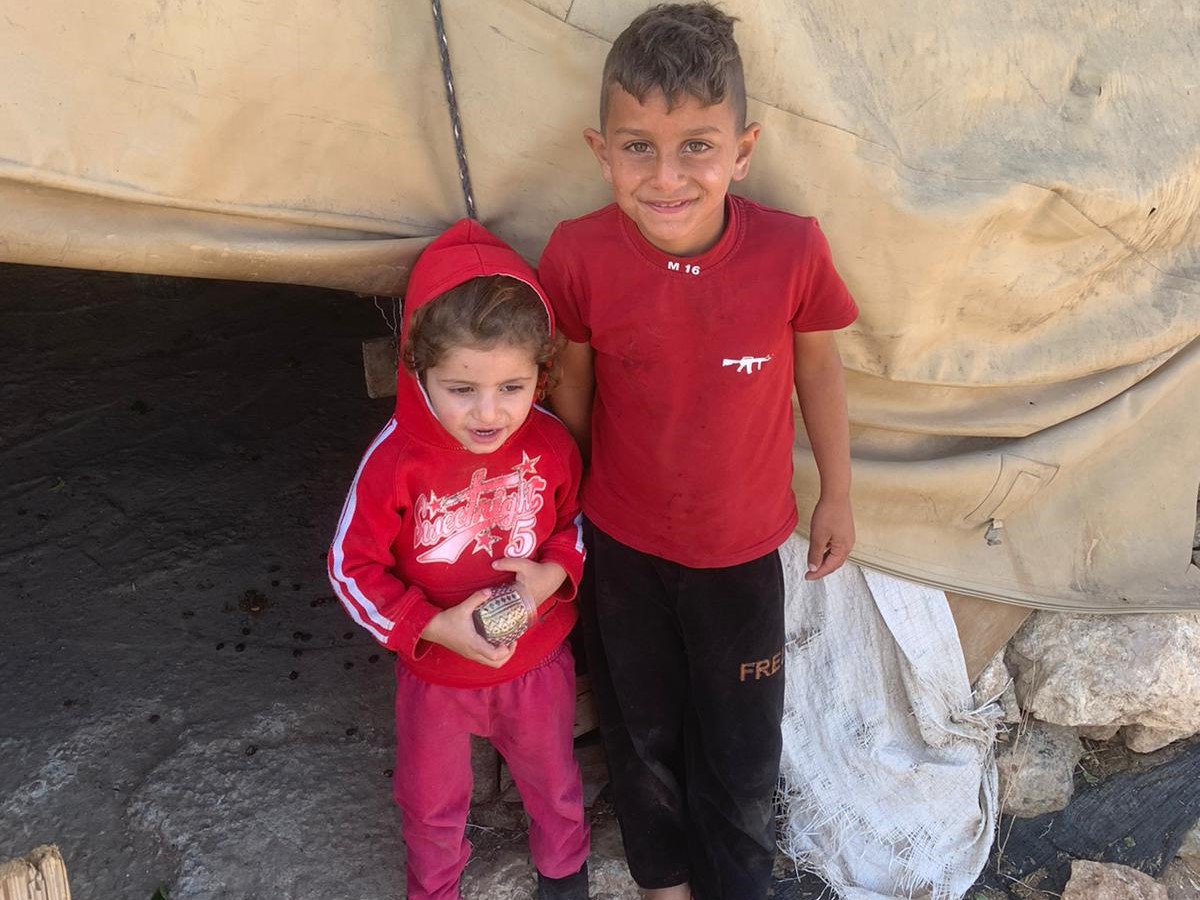

Many took refuge in mountains, public squares, abandoned buildings, or in the streets. Some crossed the border on foot after their homes were destroyed, fleeing with nothing but the will to survive. Others spend nights with 2,000 people in overcrowded shelters, battling poor conditions, lice, scabies, and a lack of water and sanitation. Teams distribute medicine and aid, while others cook in communal spaces to provide food.

Despite these efforts, it feels like we are at the start of something catastrophic, with no way to stop it—like being in free fall. Solidarity remains strong, but the need is overwhelming. People organized collections of medicines, clothes, and anti-lice treatments, while cars parked illegally now serve as homes. Makeshift shelters line the northern waterfront promenade. I saw a man lying on the sidewalk, wrapped in a blanket, tied to his motorcycle to prevent theft. The sight of him broke my heart.

Many fled the country out of fear, while others refused or could not due to limited resources. In my case, I do not want to leave. As a doctor, I feel a commitment to stay where I am most needed, here in the hospital. If doctors leave, who will help the wounded, treat patients, and care for newborns and mothers? War or not, life must go on, and this is my way of continuing to write my story and make a difference.

October 10 shocked everyone in Beirut

The recent attacks on October 10, 2024, felt devastating and unsettling. Bombs struck overcrowded neighborhoods with no Hezbollah presence. In Ras al-Nabaa, explosions hit the lower half of an apartment building non-stop as ambulances arrived in desperation. In Burj Abi Haidar, another attack engulfed a building in flames, trapping families, many who fled from the south thinking the area was safe.

One of my patients came to the hospital and when I saw her name on the list, I felt surprised she came. As an elderly woman, I thought she would have stayed home. When she appeared, she was limping without her cane. She sat down, visibly distressed, and told me she left her village 45 minutes after receiving a warning from the Israeli army. In her rush, she left behind her cane, her home, and her life. We both cried as she told her story, uncertain she could ever return.

After she left the office, I replayed her words in my mind. I wondered if I were in her situation, what would I take with me? Would I take photos and my passport? What would I save? A nurse I work with from Nabatieh fled her home a few weeks ago. Eight months pregnant, as shelling intensified she fled with her three young daughters. One was on oxygen due to neuro-physical deficits. She left everything behind, including the baby’s things. It became impossible for her to return. We organized a collection to prepare for her baby’s arrival while she stays with relatives.

Many of us fear we are on an inevitable path, much like Gaza’s ongoing conflict.

In the hospital, anxious adults and children show physical symptoms like high blood pressure as their bodies internalize the stress. Overwhelmed hospitals are unequipped to handle the wounded. In response, our hospital relocated staff from dangerous areas and secured housing nearby to ensure we can continue to provide care, no matter what comes next.

One of our secretaries fled her home due to bomb warnings. With less than an hour to evacuate, the shelling started after 15 minutes. She and her husband ran to save their lives. When I found her trembling days later, she told me tearfully that her husband returned home in the early morning to retrieve belongings. She had not heard from him since.

The devastation and abandonment have led to looting. She showed me photos of thieves tied to poles with signs saying, “I am a thief.” Recently, I had to travel for work. As I flew over the area, I glanced out the window and fear gripped me. Normally, the city glows beautifully from the air, but this time the view struck me as hauntingly different. One half of the city gleamed with light, while the other lay in a vast, dark void.

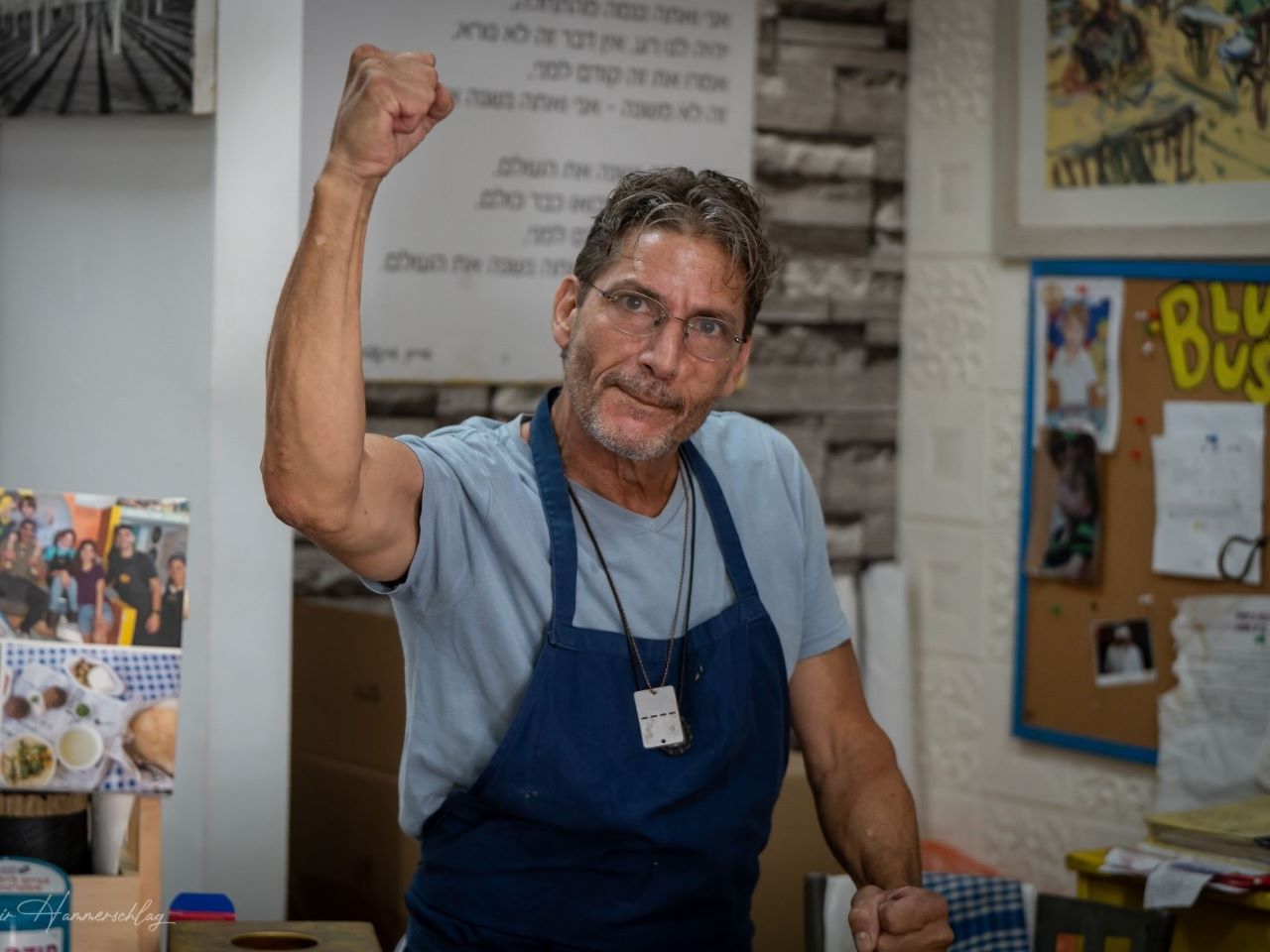

One morning, I arrived at 9:30 a.m., and the staff prepared the food. We set up an assembly line. One person added rice, another weighed it, and then someone added sauce and salad before closing the tray. We prepared 4,500 portions. This happens daily. Can you imagine the scale? We do not know what the plan is or in what direction things will go. Many of us fear we are on an inevitable path to destruction, much like Gaza’s ongoing conflict.