Refugee in Rafah: college student loses hope in Al-Mawasi camp

On February 12, 2024, At 2:10 pm, I removed my glasses and put my head on the pillow. Suddenly, the room lit up as if the sun was inside. Three bombings filled the room with debris. After the third, I ran towards my mother and sister’s room.

- 2 years ago

August 9, 2024

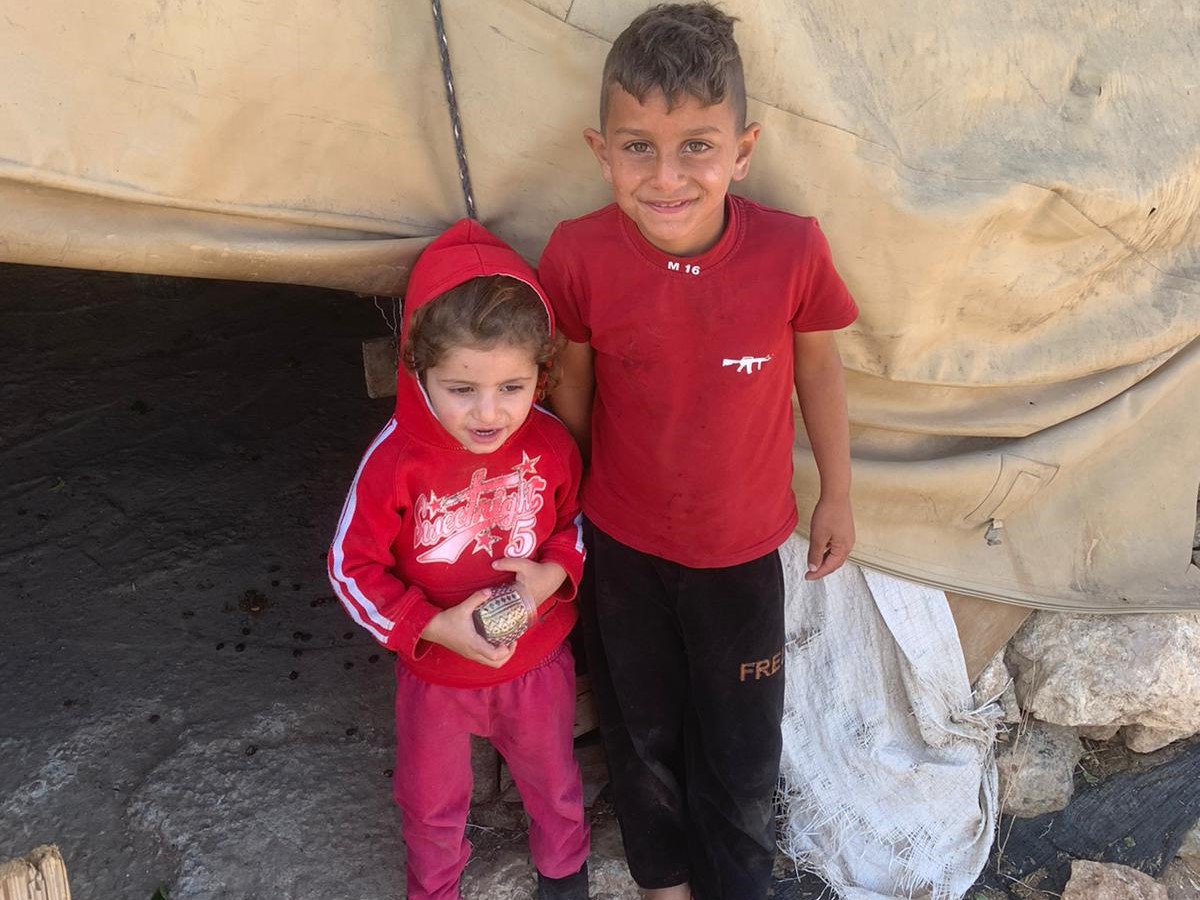

RAFAH, Gaza — After nine months of war in Gaza, horror and exhaustion envelop our lives in the Al-Mawasi refugee camp. Summer finds us underneath canvas and plastic tents or in flimsy buildings shredded by Israeli bombardments. Daily life involves searching for water, guarding our tent, scavenging for food, and cleaning, all while battling tense lethargy.

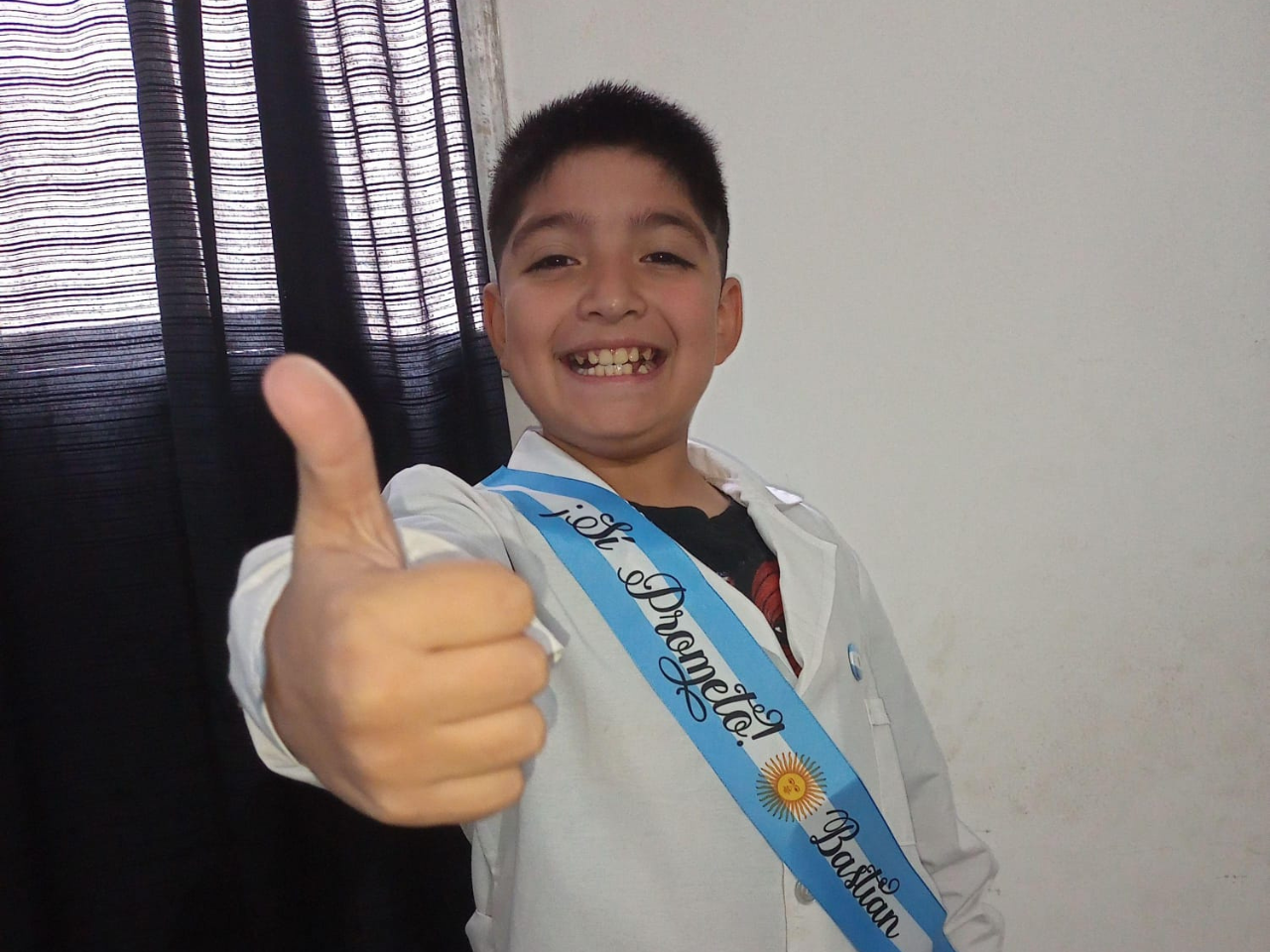

Even in designated safe zones, continuous shelling and gunfire remind us, nowhere is safe. My family and I survive daily in one of thousands of tents. This life stands far away from my dream to return to university to finish my second year.

Read more stories Gaza and from Israel at Orato World Media.

Seeking safety in the south: escaping attacks in Gaza

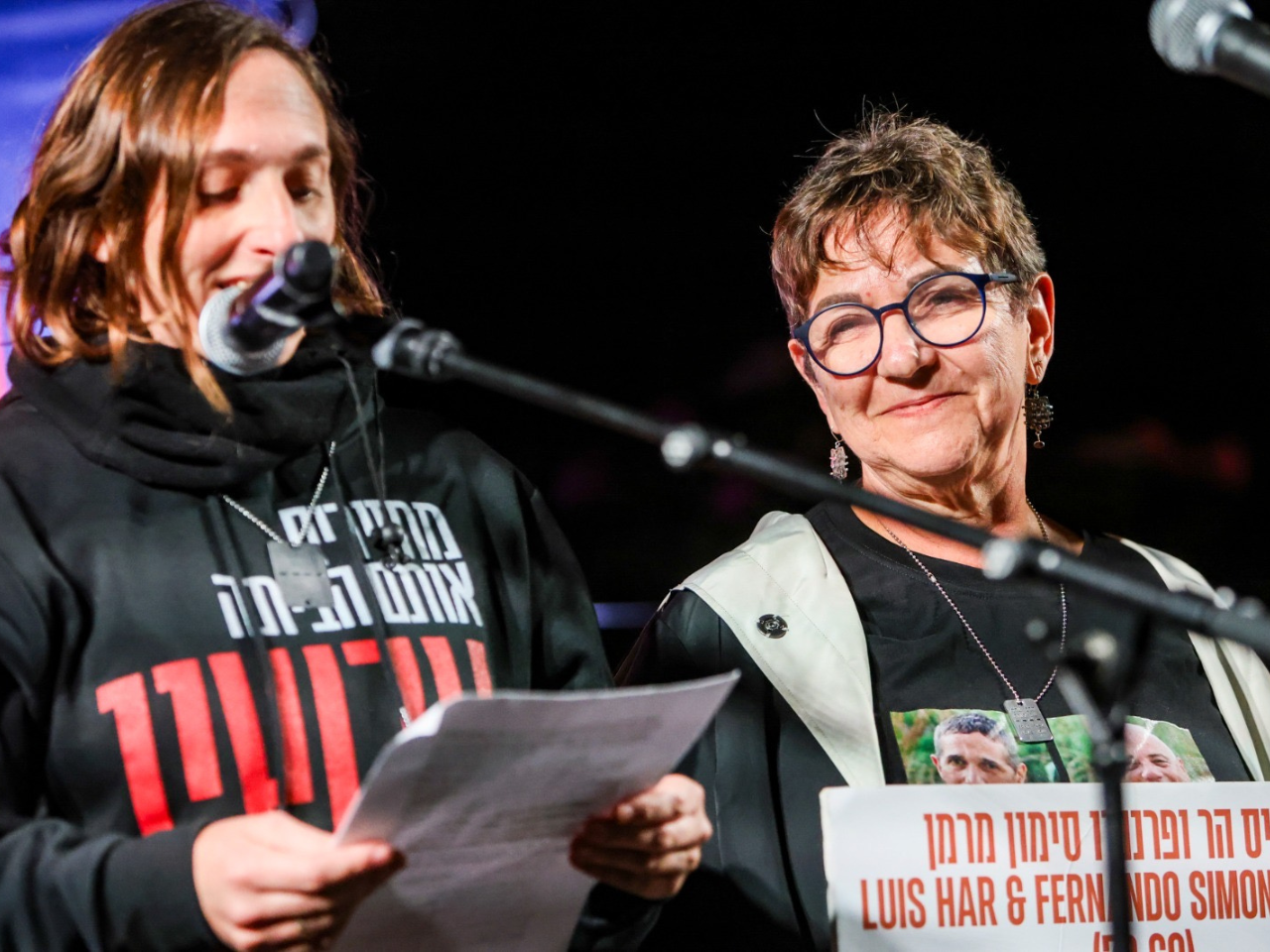

On October 7, 2023, war broke out when Hamas attacked Israeli kibbutzim and areas bordering the blockade fence around the Gaza Strip. My family and I lived in the Al-Rimal. My mother, father, sister, twin brother Mohammed and I enjoyed life in our affluent neighborhood in northern Gaza.

We endured a month of heavy shelling at our home and experienced the start of the Israeli army’s ground operation. When the Al-Shifa Hospital became overrun, we headed south to escape the attacks. Fleeing on foot, at times we jumped and dodged to avoid stepping on dead bodies in the Netzarim area, surrounded by the deafening echoes of war. It felt like they left the bodies there intentionally to create panic and effect us mentally.

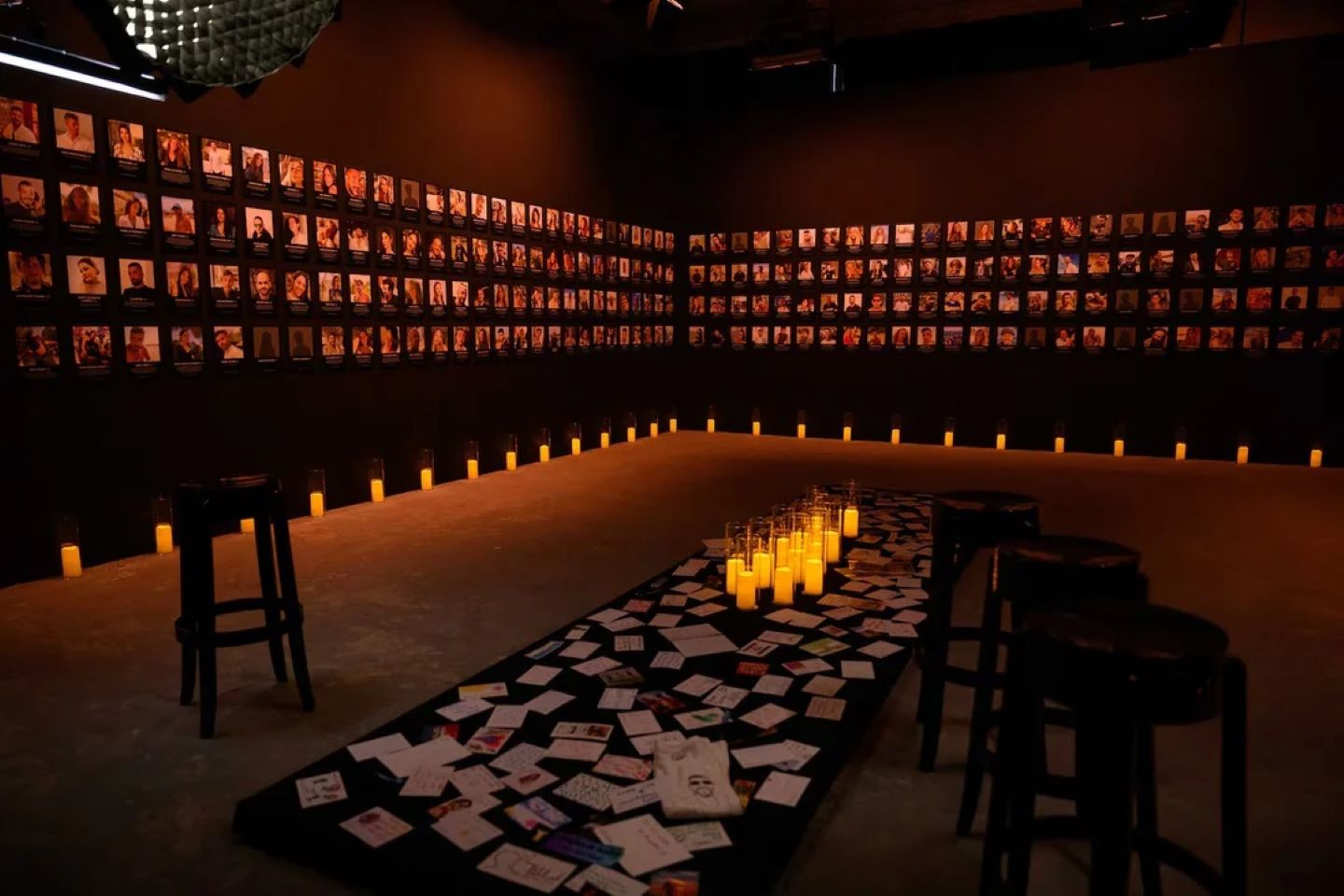

A week later, we learned that a bomb struck our building, causing us to lose our home and 14 family members. Initially, pamphlets and cell phone messages instructed us to go to declared safe areas. Following these instructions, we sought refuge with family members living in these zones. We arrived in Rafah, where we stayed for a few weeks.

On February 12, 2024, At 2:10 pm, I removed my glasses and put my head on the pillow. Suddenly, the room lit up as if the sun was inside. Three bombings filled the room with debris. After the third, I ran towards my mother and sister’s room.

A fourth bomb brought the roof down just before I reached them. My twin brother and I dug our mother out, finding her unconscious but alive. We then rescued my sister, buried three feet under rubble, alive but vomiting blood. Seconds later, another bombardment trapped us in the debris.

Bombing strikes in Rafah, mother dies in the car ride

I began shouting for help. A couple boys came to us and helped carry my mother. It took over 40 minutes for the ambulance to reach us, while the boys took my mother to the hospital in a neighbor’s car. During the ambulance ride, I felt desperate, unaware my mother died on the way.

At the hospital, I found her among piles of dead bodies, with most of her bones broken and covered in blood. Meanwhile, hundreds of wounded people arrived at the hospital. I went into shock, unable to understand anything. I injured my leg while digging through the rubble but had not even noticed it. The shock proved so great, I felt unconscious, not realizing I needed urgent medical treatment.

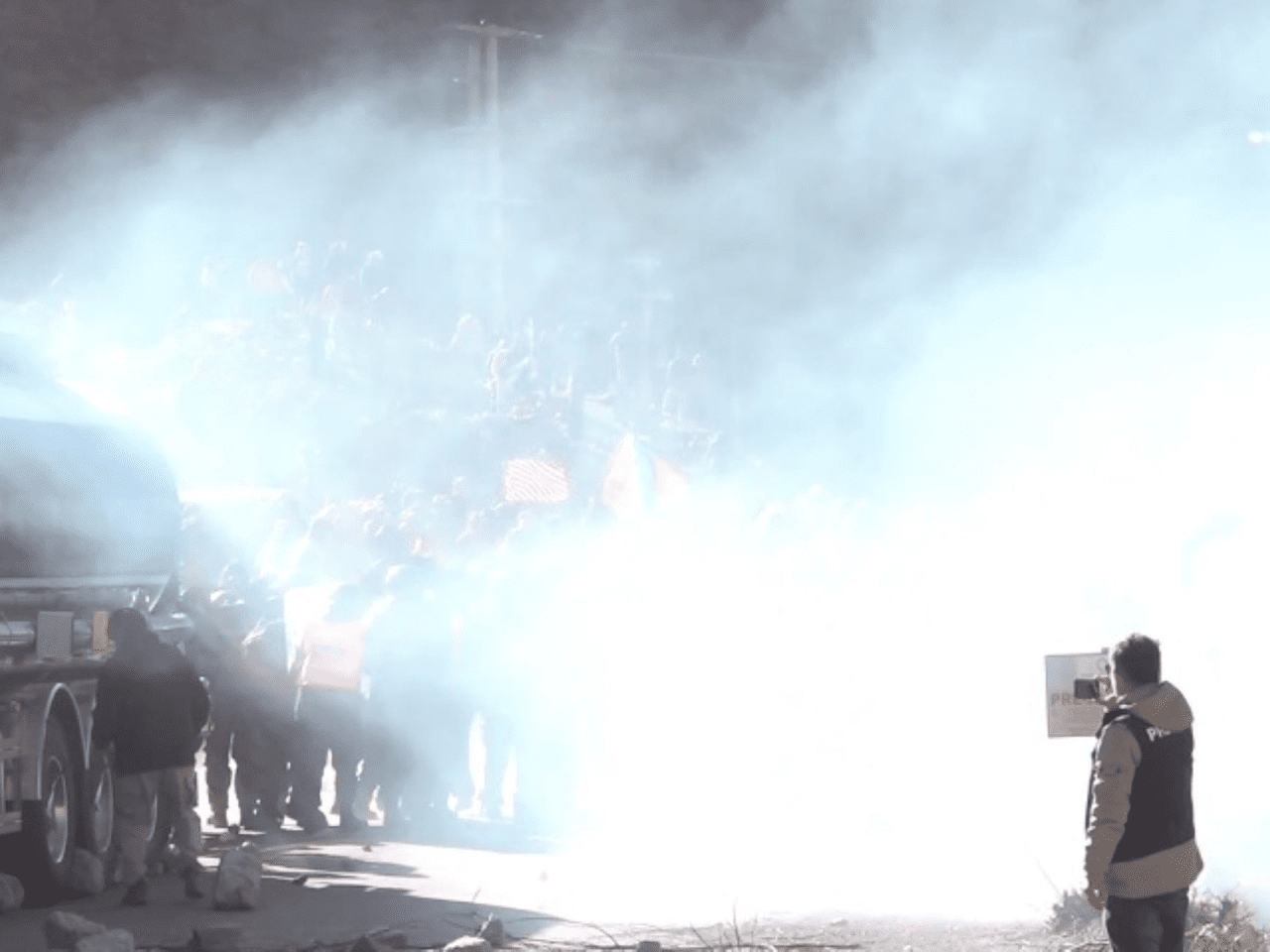

After a few days, we moved a few kilometers away. We stayed for two months there, until another bombing struck less than 300 meters from our tent. The military attack burned and destroyed the camp, killed four people, and wounded countless others. The cries of pain proved heartbreaking, and we felt safe nowhere.

We relocated again, needing a new tent and a safer camp, eventually reaching the village of Al-Masawi. Three hundred meters from the beach, we setup our tent in a vacant lot and dug a hole nearby to serve as a toilet. At night, my brother and I stayed outside to guard to the tent.

A nightmare in Gaza: surviving war under tarps

Under the tarps, we use mats and carpets as floors, beds, tables, and seats, but vermin almost always infest them. Human and animal excrement fill the surrounding area due to the lack of a latrine system. Hunger runs rampant, and we survive on sporadic and insufficient humanitarian aid.

Every night, my father wakes up screaming from nightmares, often at the exact time my mother died. Once, his nightmare saved him when a bomb exploded nearby, causing a rock to land just centimeters from his head. Bombs become a constant presence in Gaza, and I learned to interpret their sounds. When an attack comes close, the air pressure becomes so intense it renders you deaf. You only see flames and incinerated skin.

With every loss and failed truce negotiation, each day in the refugee camps erases possibilities like a blackboard wiped clean. Amidst this turmoil, I mourn my mother, feeling an emptiness in a reality full of uncertainties. I long for this war to end so I can resume my life. In our small tent, we attempt to meet our basic needs while grappling with the loss of normalcy.

Recently, Israeli forces attacked and encircled the Al-Masawi camp, making movement impossible and forcing extreme survival measures. Hepatitis runs rampant with hunger and filth everywhere. Fear and anguish become evident in people’s eyes.

I once dreamed of being a programmer, solving problems, and starting a computer company with my brother. Today, my university sits in ruins. Four professors, the rector, the head of my department, and many classmates died. Life felt simple before the war. I enjoyed college, studying, and coding. My mother made breakfast and lunch. Remembering that chokes me with sorrow.

Bombardment in safe zones: “We are lost, without any idea of what to do”

I continue to live because I have no choice. This is survival, not resilience. People die seeking food or water like victims of an unstoppable force. Even with difficulty walking, I waited an hour for a gallon of water, not out of some source of strength, but necessity.

Today, how I feel is strange. I am exhausted from fighting to stay alive every day. In July, Israel attacked the camp with air and drone bombardment, killing dozens of people in the so-called “safe zone” near us. We miraculously survived. Here, we feel trapped, waiting for death to come at any moment. We cannot escape, return home, or find a safer place.

Today, our priorities have shifted. I search for food and water and spend eight to 10 hours a day sitting in the tent. Sometimes, the midday heat forces us out, and we sit on rocks or sand, feeling the sun on our skin and breathing the outside air.

No one expects a future; we no longer believe this will end. In the beginning, we thought the conflict may end before 2024, but it did not. Then we hoped it would end by Ramadan. Yet, things only worsen, shattering any remaining hope. Understanding this has been difficult for me.

Many people no longer listen to the news, believing nothing and no one can stop this. We feel lost, without any idea of what to do. Every day, we simply wait for something worse to happen and struggle to save our lives.