Behind the scenes of Brazil’s War on Drugs: anthropologist follows 20 unhoused women addicted to crack

For many of these unhoused women, crack represented their quest for life, not a means by which to die. Mostly victims of violence, many had fled to the streets to escape, and crack allowed them to survive without losing their minds completely.

- 2 years ago

September 28, 2023

SALVADOR, Brazil — We sat on a bench in the darkness of night, and I listened. I had been shadowing 20 women from Brazil who lived on the streets and consumed crack. As they opened up to me, their eyes revealed the full story; I saw pain and the loss of hope. For many of these unhoused women, crack represented their quest for life, not a means by which to die. Mostly victims of violence, many had fled to the streets to escape, and crack allowed them to survive without losing their minds completely.

Sitting around and talking, my heart shattered for them. They seemed resigned to their fate, no longer fighting. Their world revolved around hard drugs and the constant struggle to get by. So moved by the experience, I wrote my book Becoming A Female Crack User: Culture and Drug Policy. Too often, people assume the problem is the drug itself, but ignore the racist and sexist structures within the drug user’s history.

Read more stories from unhoused people at Orato World Media.

An unhoused mother sees her son murdered

I met one mother who lived in poverty on the streets with her son. Desperate to make money, he set up shop and began selling crack. In a terrible moment of tragedy, a group of men arrived. In front of his mother, they shot four bullets into his back.

When she relayed the moment when she watched these men execute her son, tears filled her eyes. My heart ached for the pain she carried. In the five years since his murder, addiction to crack became her sole source of comfort.

My mind drifted to how the media addresses addicts in such a dehumanizing way. How could I dehumanize this woman’s trauma? How could I not consider her past and show empathy? During my research, I accompanied the women in their attempts to access healthcare and to find shelter and maternity services. For two and a half years, I followed them, seeking to truly understand the path which led them to this life.

So many of their problems stemmed from racial and gender violence. I met women who lost a child and found themselves navigating the world completely on their own. Others endured rape and never got the justice they deserved. Of the 20 women I shadowed, 18 came from violent homes. They never intended to grow up and become addicts. In a world where they found themselves alone with no options, drugs became a familiar companion.

Police killed her right in front of my eyes

Throughout my research, I witnessed terrifying moments. While digging into the subtopic of micro-trafficking, I met a woman. Caught up in a trafficking bust, the police on scene could have easily saved her. Instead, I watched as the police shot and killed her right in front me. I stood there in disbelief, unable to move. My blood felt like it froze in my veins as I went into shock. Images of the scene haunt my mind even now. As a mother, I feel deep empathy for these women.

Conducting my work from their perspective allowed me to view the situation through a unique lens. In Brazil, unhoused women on drugs commonly lose custody of their children. While the court acts to protect the child, they simultaneously neglect the mother completely.

They take the babies, put them in an orphanage, and leave the mothers to suffer and struggle in precarious situations. Accessing services available to all citizens becomes nearly impossible. Never mind getting protection from the authorities. The latter seemingly remains reserved for those who have a roof over their heads.

In fact, the system often works against them. One woman endured a devastating assault by her partner, but when she filed a report, authorities denied her access to a women’s shelter for being homeless. Out on the streets, these women face even more violence. Aggressors prowl in the darkness, looking for easy prey. Sadly, Brazil’s War on Drugs furthered that aggression wherein the police and military apparatus became the worst aggressors. Rape and assault go uninvestigated.

Seeing the violence firsthand against unhoused women in Brazil, we decided to do something. When we concluded our research, we launched a collective space designed to offer these women a chance to discuss the violence they encountered and teach them to protect themselves.

Unhoused women who use crack lack meaningful services

Spending over two years following these 20 unhoused women in Brazil, I listened to story after story about violence – often at the hands of the authorities. I witnessed their deep-held belief that it was all their fault. Abandoned, blamed, and devoid of support – they became victims twice over, both from their early lives and from the very system meant to protect them.

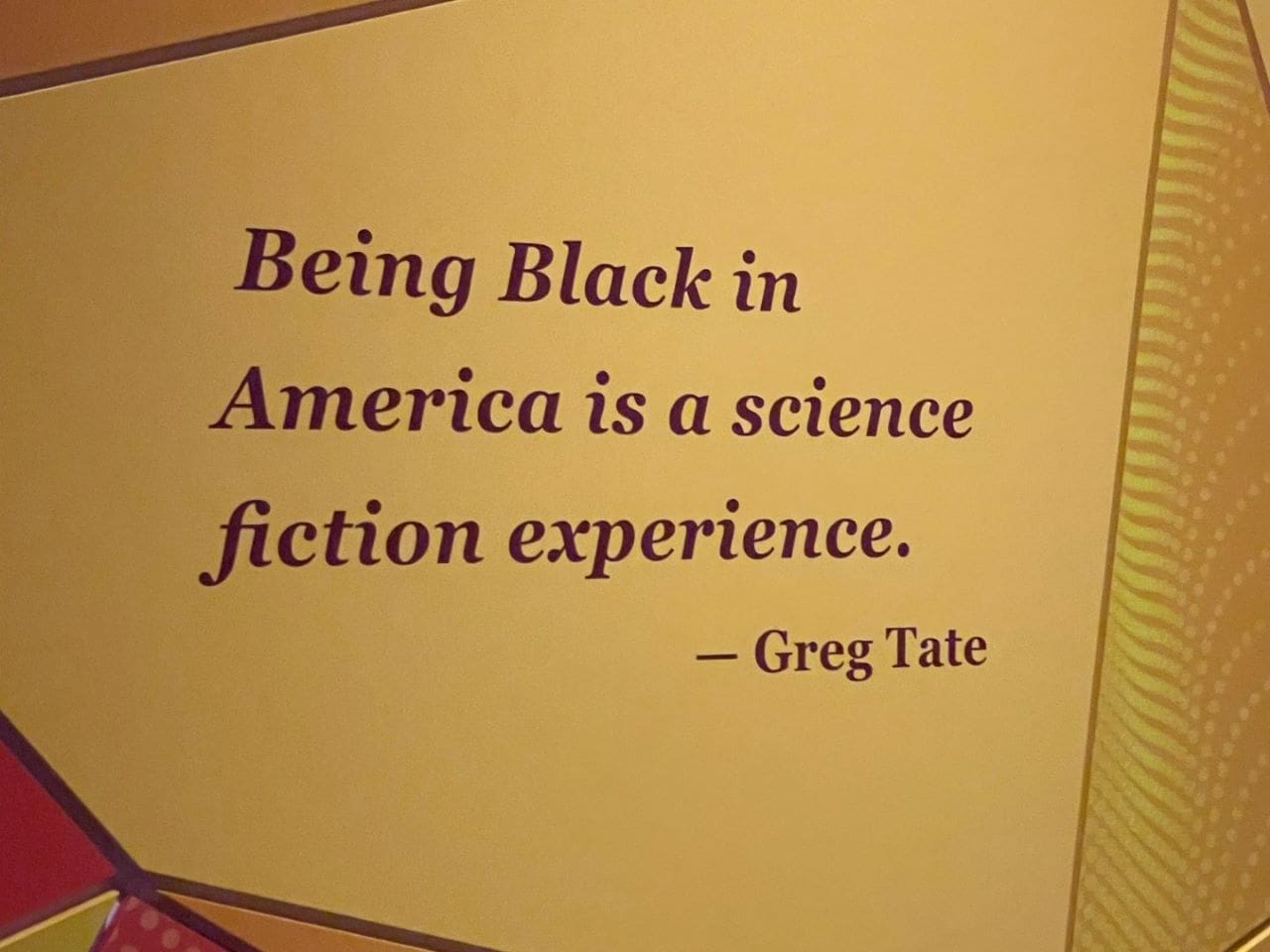

I needed to dig deeper and began to ask these women about the political side of their situations. We examined the lack of funding and protection in poor neighborhoods and the connection to systemic racism. The Brazilian drug policy seems to offer more protection to white people whilst criminalizing the black community.

For the 20 women I met, I learned a great deal about that criminalization. When problematic substance abuse enters the equation, they find themselves more often incarcerated than in healthcare or rehabilitation facilities – reinforcing the stigma that already surrounds addiction.

Young black men and women disproportionately die in the war on drugs. We must do better. We must find solutions that offer addicts a pathway to regain health and independence, rather than alienating, marginalizing, and criminalizing them.