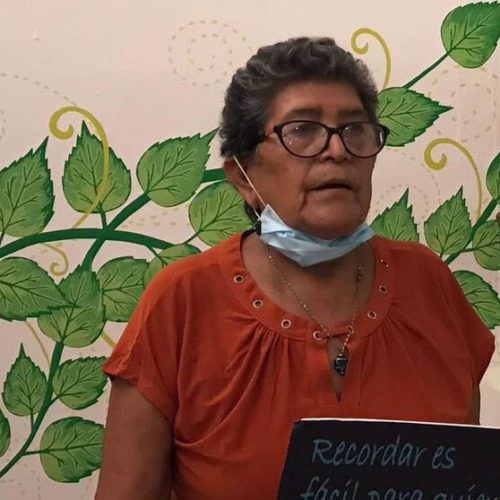

Woman seeks justice for siblings who disappeared 42 years ago in El Salvador’s armed conflict

The guard took my brother off the bus by force and threw him to the ground. They beat him without any explanation. The bus continued on its way. I never heard from him again.

- 3 years ago

September 20, 2022

SAN VICENTE, El Salvador — I saw my brother for the last time on May 2, 1980. He fell victim to forced disappearances during El Salvador’s armed conflict.

We grew up in Verapaz, a small municipality in the department of San Vicente. Though my family came from a low-income background, my parents always taught us that poverty does not negate your human rights.

At the age of 37, I learned the term forced disappearance and began to understand why I never saw my brother again after that afternoon in May.

The forced disappearance of my brother after being captured by the Guard

My brother, Juan Francisco Hernández, served as a catechist [a lay member of the Christian faith devoted to teaching and missionary work]. The National Guard in El Salvador persecuted him for being unruly. Days before his disappearance, around 10:00 in the morning, I heard they were coming to search our house.

I sent one of my sisters to tell Juan to leave Verapaz so they would not find him. He fled and escaped. We never knew where he went or who he went with. However, the Guard continued to harass us, and eventually, we also left our home.

On May 2 at 3:00 p.m. I heard news of my brother. An acquaintance of his came to tell us the Guard took Juan. He explained what he saw. At 1:00 p.m., they stopped the bus going from Guadalupe to Tepetitán. A checkpoint with about 20 soldiers stopped the bus. Five of them boarded the bus and went directly to Juan.

The guard took him off the bus by force and threw him to the ground. They beat him without any explanation. The bus continued on its way. I never heard from Juan again.

The persecution of my family endured

The driver, whose name I never learned, may have known my brother and gave him up to the Guard. My brother’s acquaintance said the bus took an unusual direction to arrive at that checkpoint – the place where one of many executioners who wanted my brother dead awaited him. The next day, from the early hours, my family and I began looking for him.

Someone told me that they saw him floating in a river. I rushed over but did not recognize any of the bodies. What I saw proved horrid: naked and completely disfigured bodies with their faces cut open. Every victim in the river proved unrecognizable.

A few months later, I saw one of my brother’s persecutors. Face-to-face with each other, he laughed ruthlessly. He told me he and the others enjoyed beating and torturing my brother before killing him. The man warned me, if I wanted to know where my brother was, I had to go back to Verapaz. He said he would gladly take me to Juan. I did not accept his offer and never saw that man again.

I visited hospitals, morgues, and prisons but found no information. My family and I also faced persecution. If I returned to my native Verapaz, I might as well sign my own death sentence.

Now, at 79 years old, I have waited for justice for 42 years. Not only did two of my brothers disappear that year, the Guard and National Defense of my country later murdered my husband. After many years of exile, they eventually captured me. I suffered offenses, mistreatment, and imprisonment until my release.

Continuing to search for my brother

As a Catholic and a Romeriana, I often quote Luke 23:31, “For if they do these things in a green tree, what shall be done in the dry?” The verse makes me reflect on the fact Saint Oscar Romero fell victim to premeditated murder to silence his public complaints. How could they not want to do the same thing to my brother? Many Salvadorans went through forced disappearance before and during the armed conflict.

The Truth Commission registered complaints of 5,000 disappearances; however, human rights organizations count more than 9,000 before and during that time. I will never tire of looking for my brother; I am one of thousands of voices of mothers and siblings who lost family members. Together, we are the product of those who see us as “dry trees.”