Regime in El Salvador ignores civil liberties, detains and beats an innocent college student

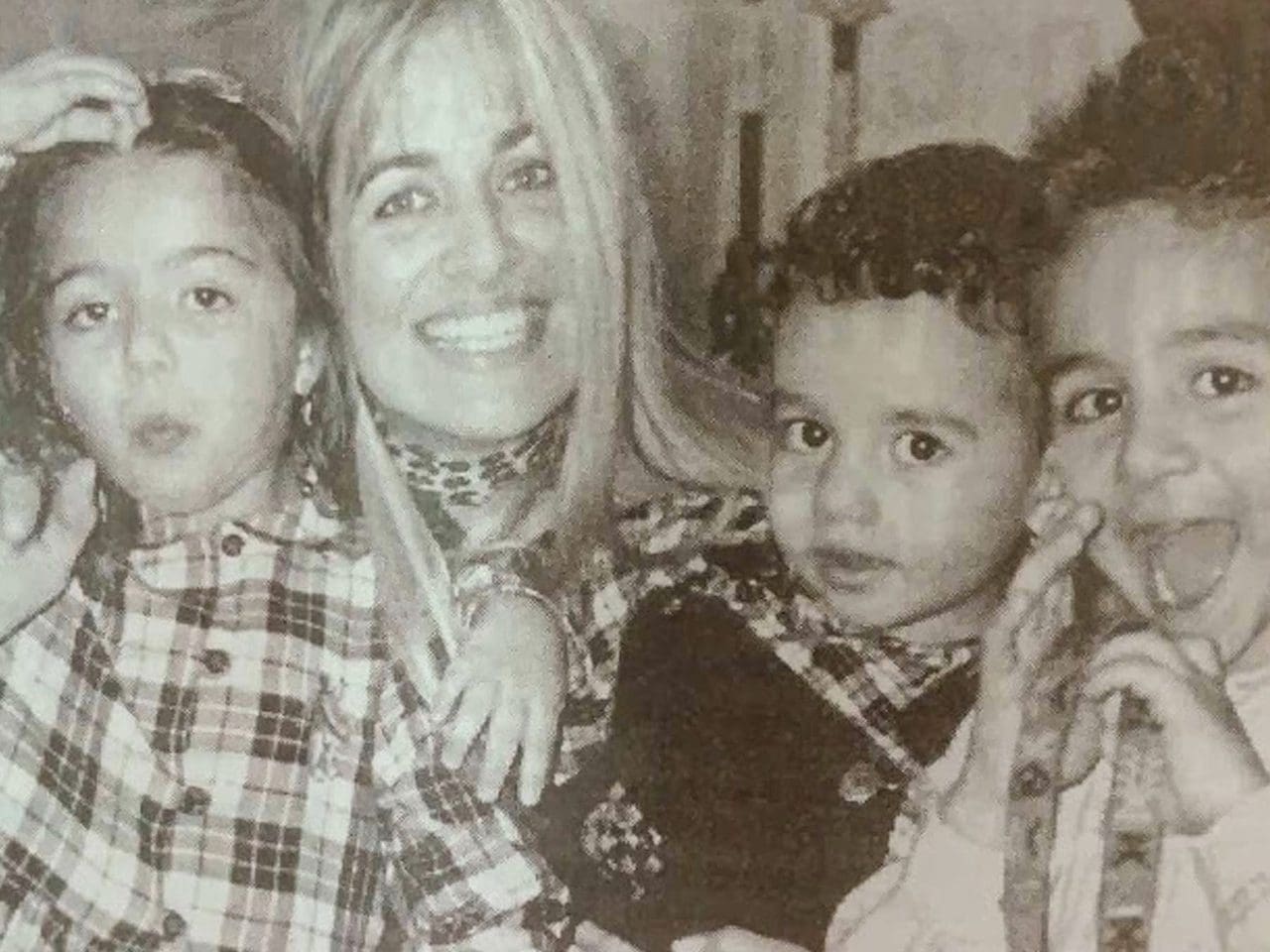

My parents live without any peace of mind today. They felt some joy over my release, but deep down, they worry every day about my brother. He acted as their right hand and helped the most in terms of work and finances. Since that fateful Tuesday night, happiness ceased to exist in my house.

- 3 years ago

November 20, 2022

LA LIBERTAD, El Salvador — On Tuesday, April 19, 2022, life changed forever for my family. My brother and I went about our regular routine of school and church, comforted by the shelter of calm silence. Then, suddenly, military soldiers from El Salvador’s “exception regime” arrived at our home.

Thier presence disrupted our lives. The soldiers detained us, though we committed no crime. They let me go but my brother remains in prison.

Unexpected military stop on the way home from school

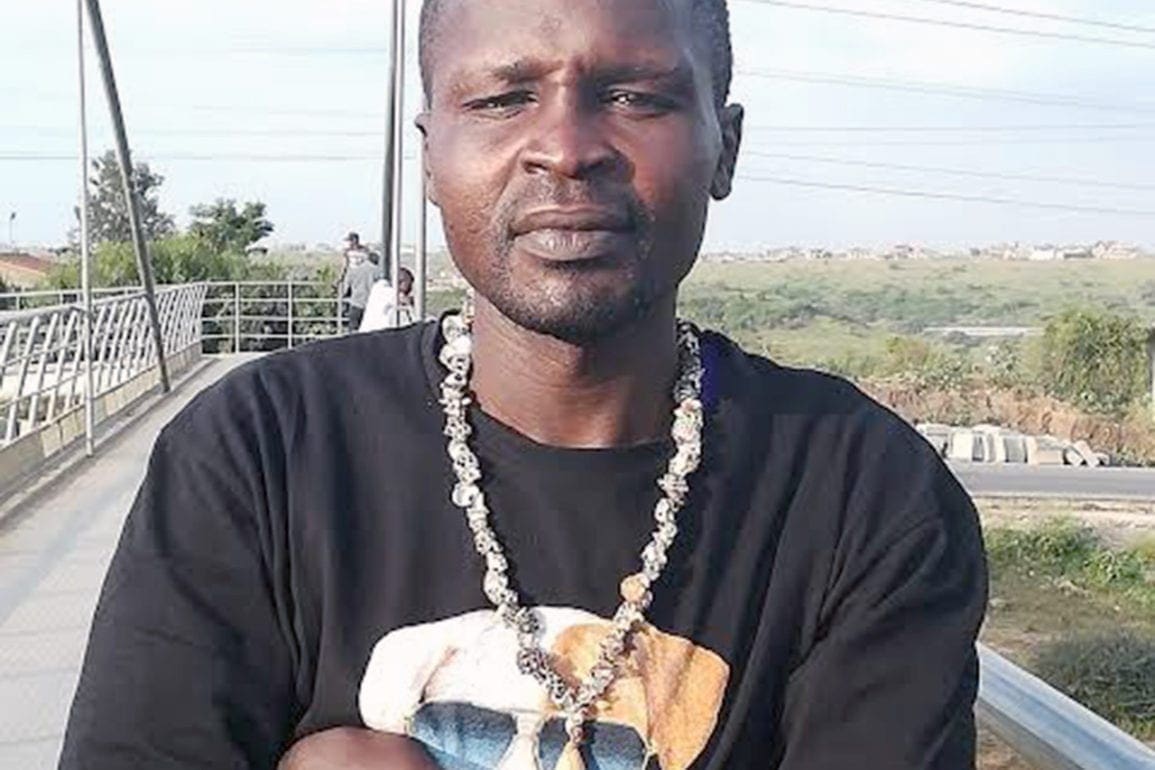

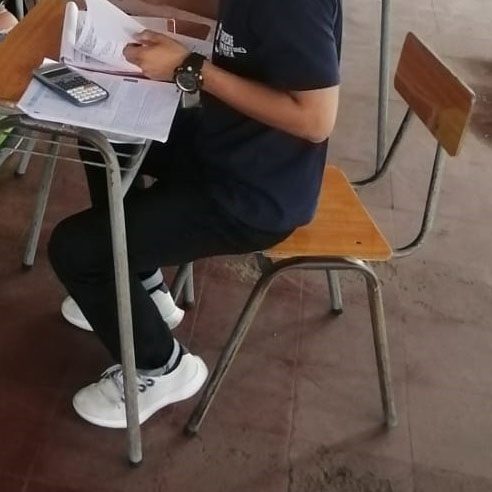

On a typical Tuesday, I remained at home with the flu. The medication my doctor prescribed the previous day helped me carry out the final tasks for my classes at the university. The next day, my family planned to leave for vacation. By the following week, I anticipated being back in classes.

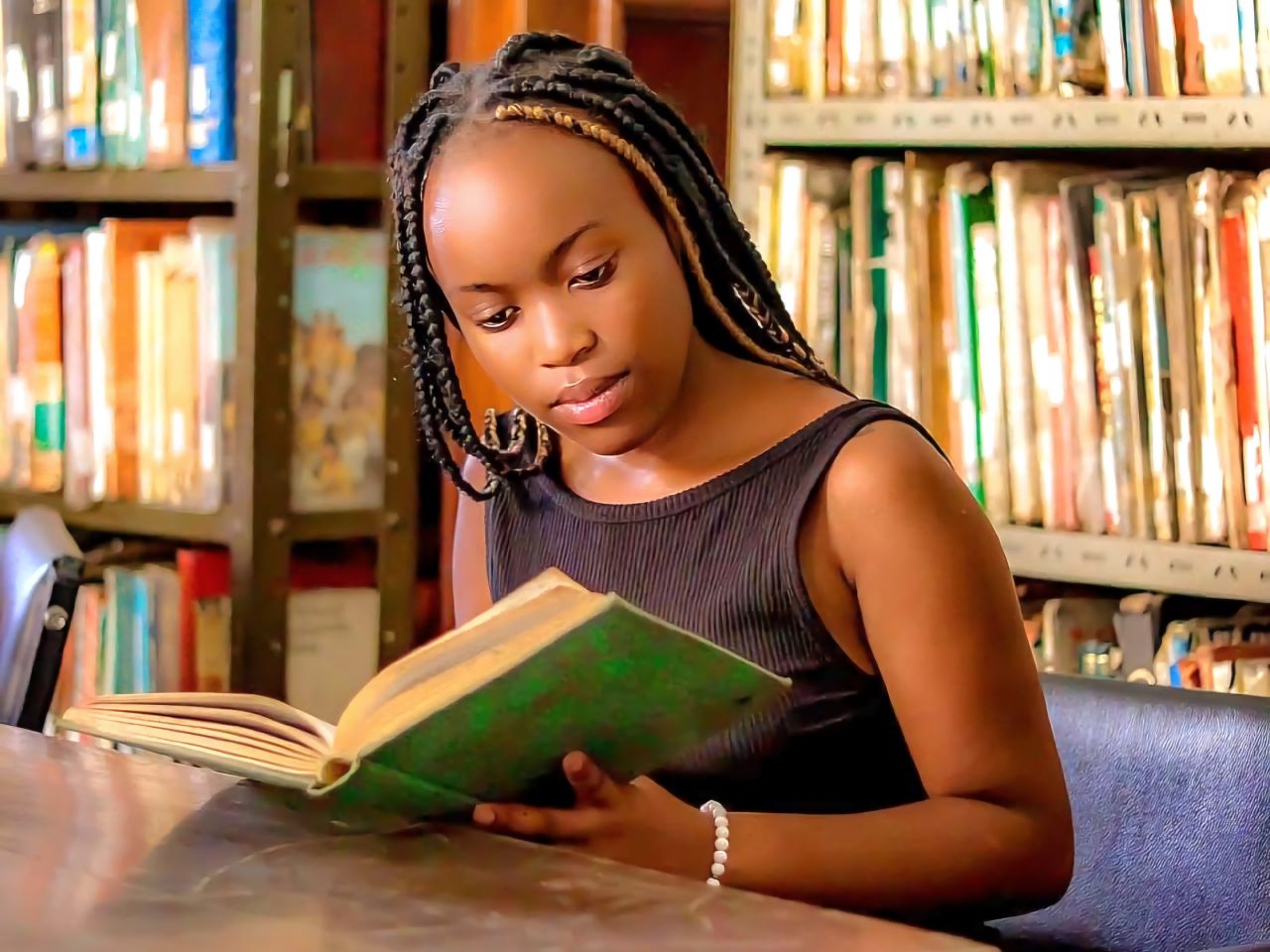

I woke up Tuesday in much better health than the day before. Nothing happened that day to give us any inkling of the drastic events to come. I went to the library to finish my homework and forward my assignments to a classmate, because I had no internet at home.

I arrived at the library at 7:00 p.m. while my brother went to his church service. Afterwards, he met me at the library to pick me up. I finished up my homework and by 11:20 p.m., we headed home. We followed our typical route – a 20-minute motorcycle ride.

At 11:40 p.m., we reached the last street leading to our house on the farm when a car from the armed forces stopped us. The two officers conducted their “routine” investigation as part of the ongoing exception regime in El Salvador.

The officers searched us and asked about the “bichos” which translated literally means bugs. In this context, they referred to gang members. They found nothing on us and told us to go home. We heard about such routine checks and did not worry. After all, I made it home from school and my brother made it home from church.

Young men stripped and searched for gang tattoos

When we arrived at the patio of our house, we met with five more military soldiers searching the house. They began to question my parents about the number of people who lived there. On seeing the two of us, they stopped us and moved us to the side.

With an intimidating attitude, they asked for our phones. They checked my brother’s phone first. One of his contacts, saved with no name, caught their attention. I knew the number, like everyone else in our neighborhood. It belonged to a man who sells beans in the community. My brother never saved it to his contacts.

The discomfort could be felt in the air. They asked aggressively why the number did not have a name associated with it. My brother and I said nothing. I watched as my brother became increasingly nervous. When they asked him for the name, he began to ramble, and that reaction triggered our arrest.

The soldiers turned to me and asked me to take off my sweatshirt to see if I had any tattoos. I took it off, and they saw I had none. I told them it was time for them to stop; I had no tattoos or anything incriminating. Those words bothered them more. They accused us of “talking back.”

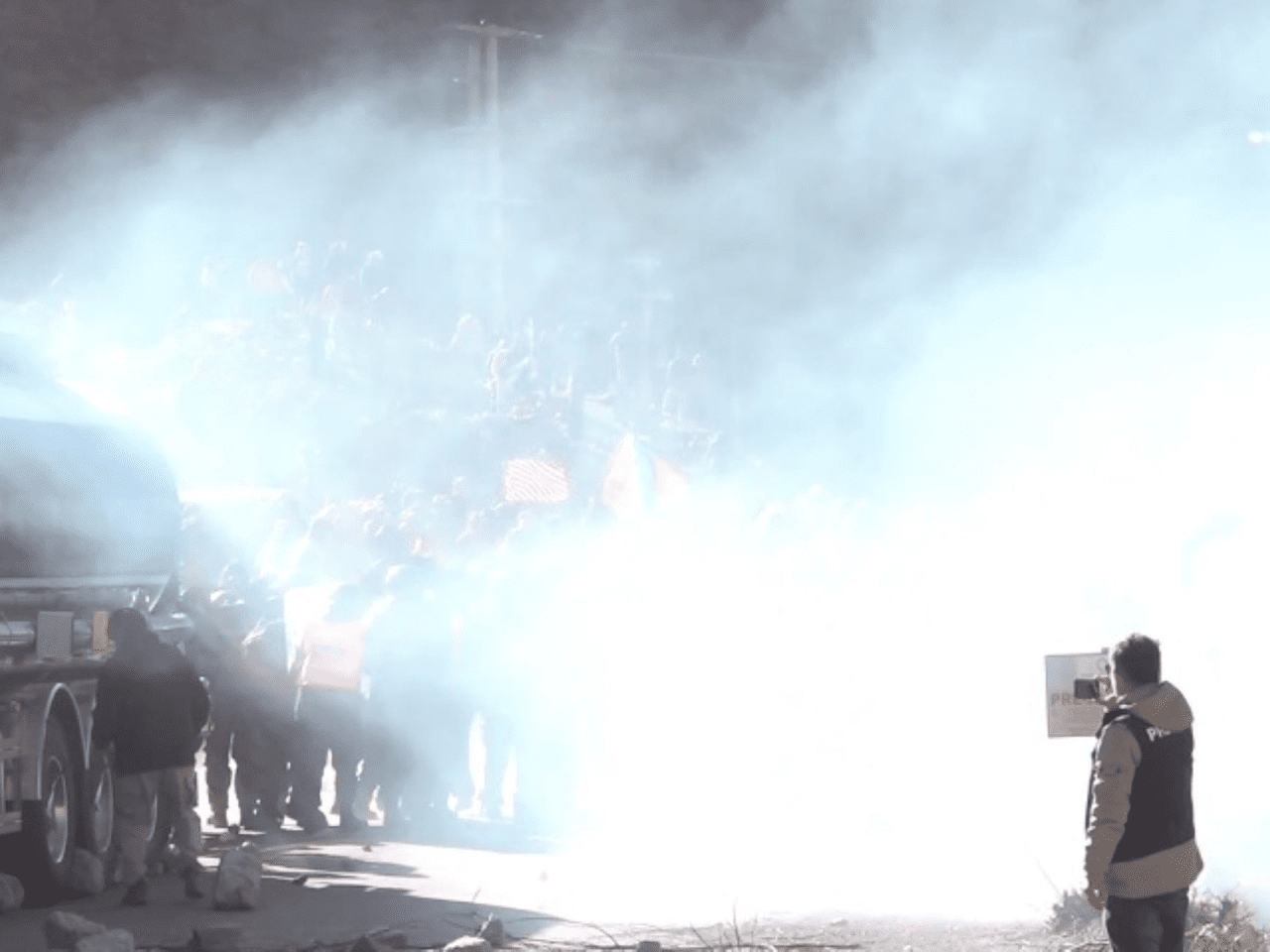

More detainees held on the street, handcuffed and kneeling on stones

We felt shocked when they moved us to the back of the house, asked us to kneel, and continued questioning us. That night they found two coal workers nearby, known as charcoal burners. They had the two workers kneeling in the same place where took us. After 10 minutes of interrogation, they moved us to the main street intersection. They handcuffed us and asked us to walk without looking back.

I thought that only the four of us would be taken, but I was wrong. They awaited more people, captured in other cantons, or small regions around where we lived. I remember telling my parents not to worry because we did nothing. We reassured them, this was a routine activity. In all honesty, we never expected the situation to escalate. However, the military told our parents they detained us for the crime of being part of “illegal groups.” We assumed they did this simply to intimidate us. Losing control of the situation never crossed our mind.

On the street, we waited for more than an hour, kneeling on stones. By 1:20 a.m., we began to see more captured people joining us. At no point did they take away our cell phones, which they returned to us after the first interrogation. With my cell phone in my bag, I thought I need not worry. I heard stories from the past indicating those taken by the regime had their cell phones removed immediately. I thought everything would work out.

Hours pass as police and military officials argue

Soon, four pickup trucks arrived. They placed me, my brother, and the two workers in one truck. The truck took us from the entrance to the main street to a military headquarters in the area. They lowered us from the trucks and placed us on our knees. All together in a group, the detainees from all the trucks kneeled together. They took pictures and publicly introduced us on social media as captured criminals. After that, at 3:00 a.m., we moved to the police station.

I heard a military sergeant tell the police commissioner they would move us to a correctional center. Apparently, this constituted regular procedure. The commissioner replied, he does not follow that procedure anymore. As they filled out paperwork, it became clear a discrepancy brewed between the military and the police. It took an entire day to resolve before they moved detainees to the penal center.

I remember the discussion and discomfort between the two authorities going on for two hours. They each made calls to different people. As time went on, more members of the armed forces came to relieve the ones who detained us. We stood in a line until they finally let us sit, unable to talk to one another. Sitting quietly, we watched what happened. At 8:00 a.m., they took us to a nearby field and sat us down again in a single row until 10:30 a.m.

One brother released, the other sent to prison

The military again separated us, and the police began asking each person about their criminal records. The military soldiers also handed over the things taken from some of us that night. They informed the police of the crime(s) for which they captured us.

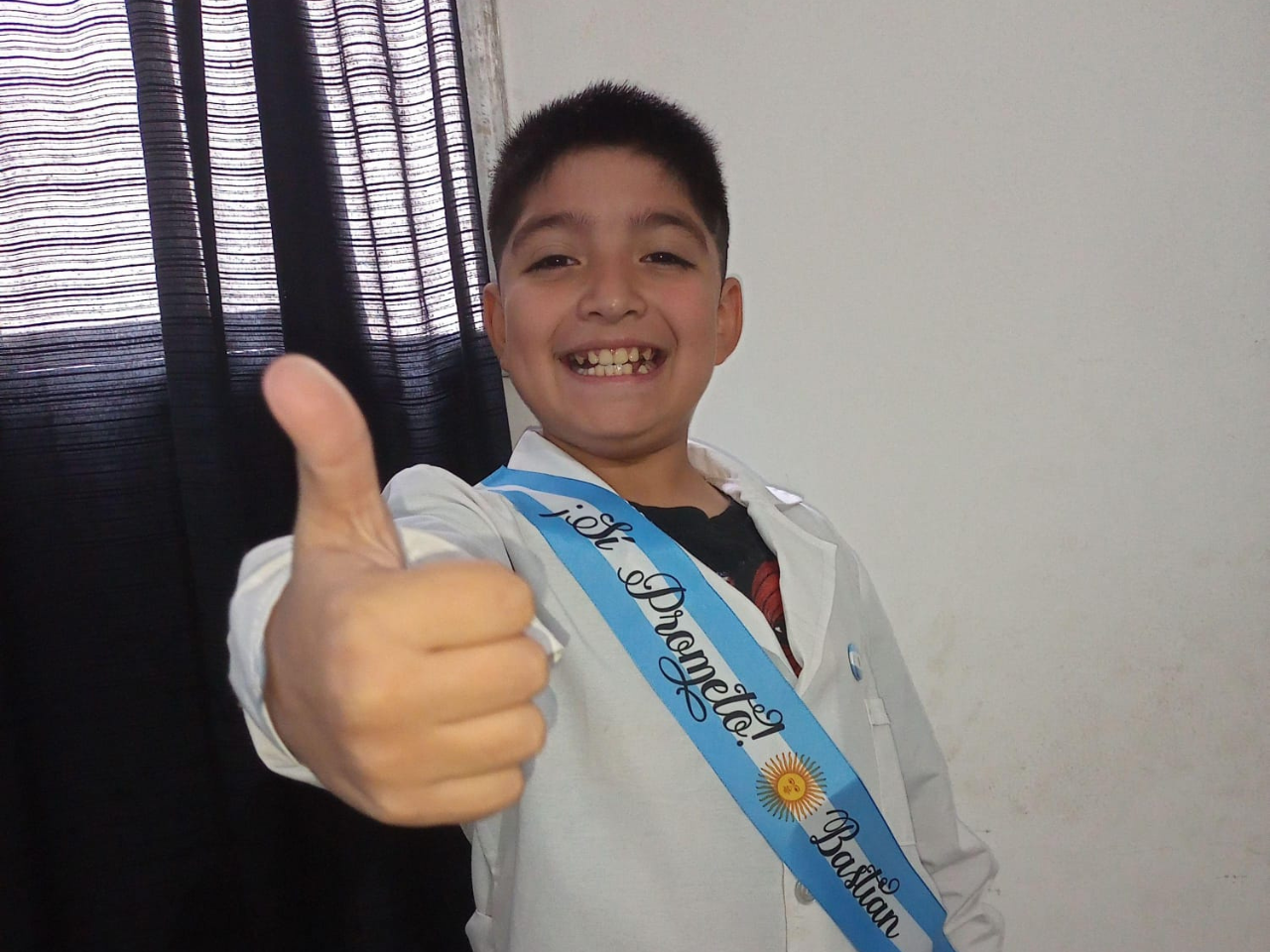

The whole proceeding lasted a half hour. They separated the minors from the adults. While they moved me, they placed my brother among the people who, according to the military, had involvement with something illegal.

We kept our cell phones but could not make calls. I wanted to call a friend to let him know I would not be turning in my homework on Wednesday. They warned me not to say what was happening. I decided not to reach out to my friend in fear the authorities might think I gave up information.

From afar, I saw my brother but could not hear the charges they accused him of. At 11:00 a.m. they released those of us not directed to the correctional center. They gave us a release letter and told us to leave but required that a legal representative pick us up. My father took responsibility for me.

The sub-sergeant of the military came out and told my dad he would call out the names of those being freed. They called the individuals, one by one, and released them, until my turn came. In five minutes, everyone named went outside. The tension of the moment blurred my sight. I did not count the number of people. I wondered why I got out and my brother did not. Outside, my father and I waited from 11:00 a.m. until 3:00 p.m. for my brother to be transferred to prison.

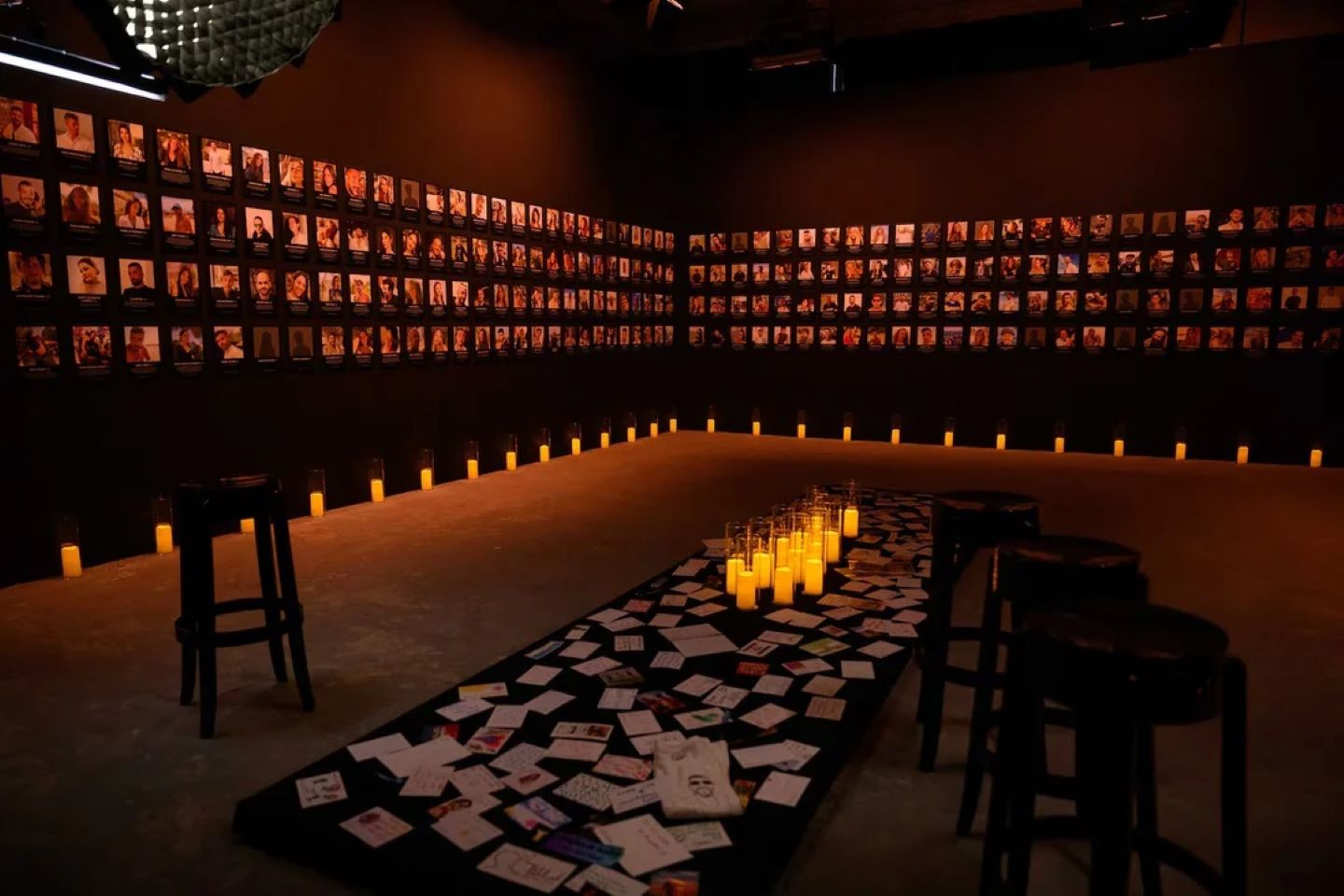

Family left with a sense of despair, many mothers see their children taken

By then, the confidence I had in our safety turned into uncertainty. We went from calm to total despair, with no idea what might happen or how long it could take. When they took my brother, I thought the nightmare would end quickly – perhaps in a day, a week, or a few weeks at most. After all, we did nothing wrong. My brother still has not come home.

My parents live without any peace of mind today. They felt some joy over my release, but deep down, they worry every day about my brother. He acted as their right hand and helped the most in terms of work and finances. Since that fateful Tuesday night, happiness ceased to exist in my house.

The group of people they captured included people who committed crimes, but also innocent individuals like me and my brother who did nothing. They take people like my brother just to meet a quota. To this day, I cannot come to terms with what happened. I don’t think I ever will.

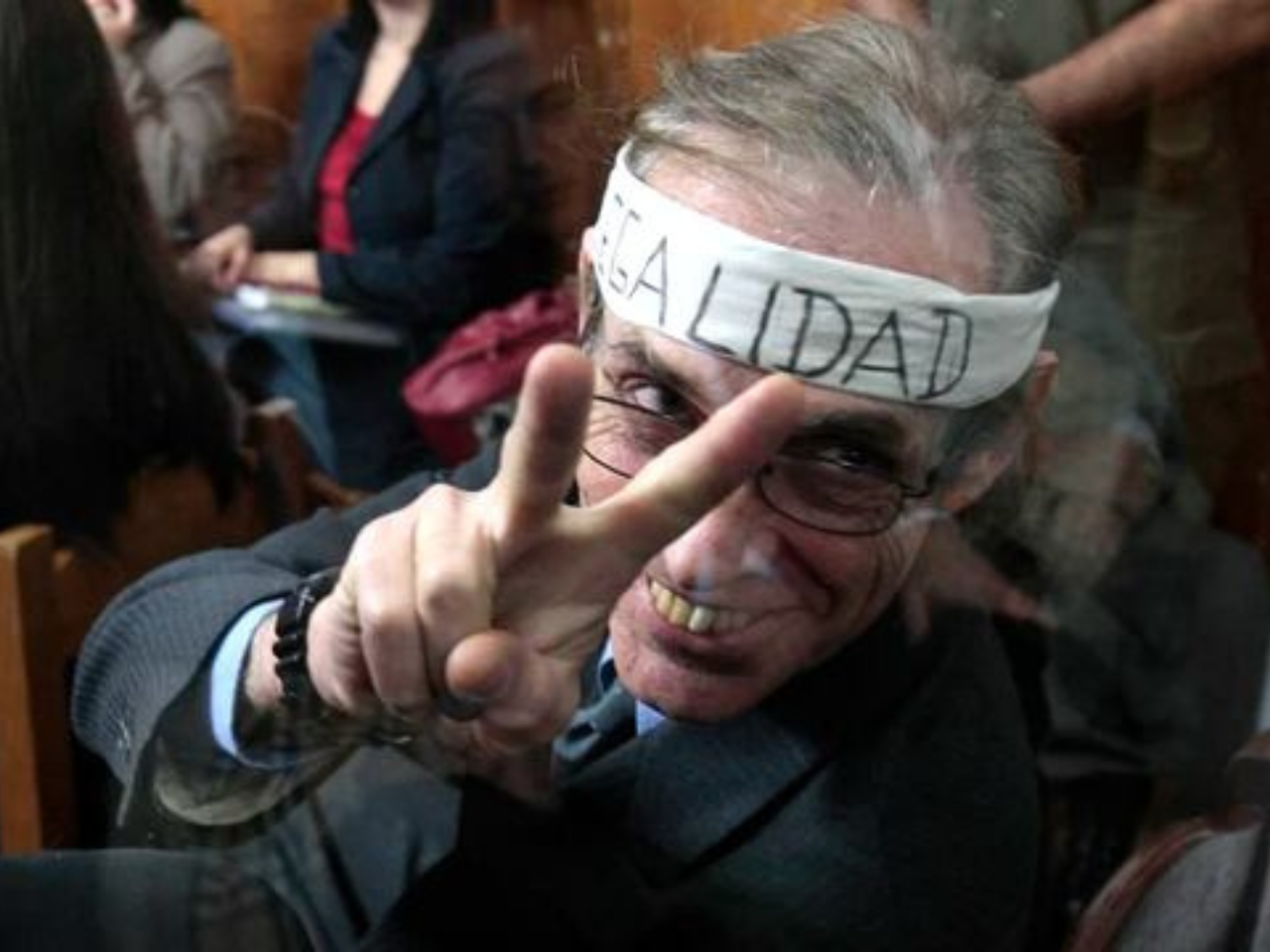

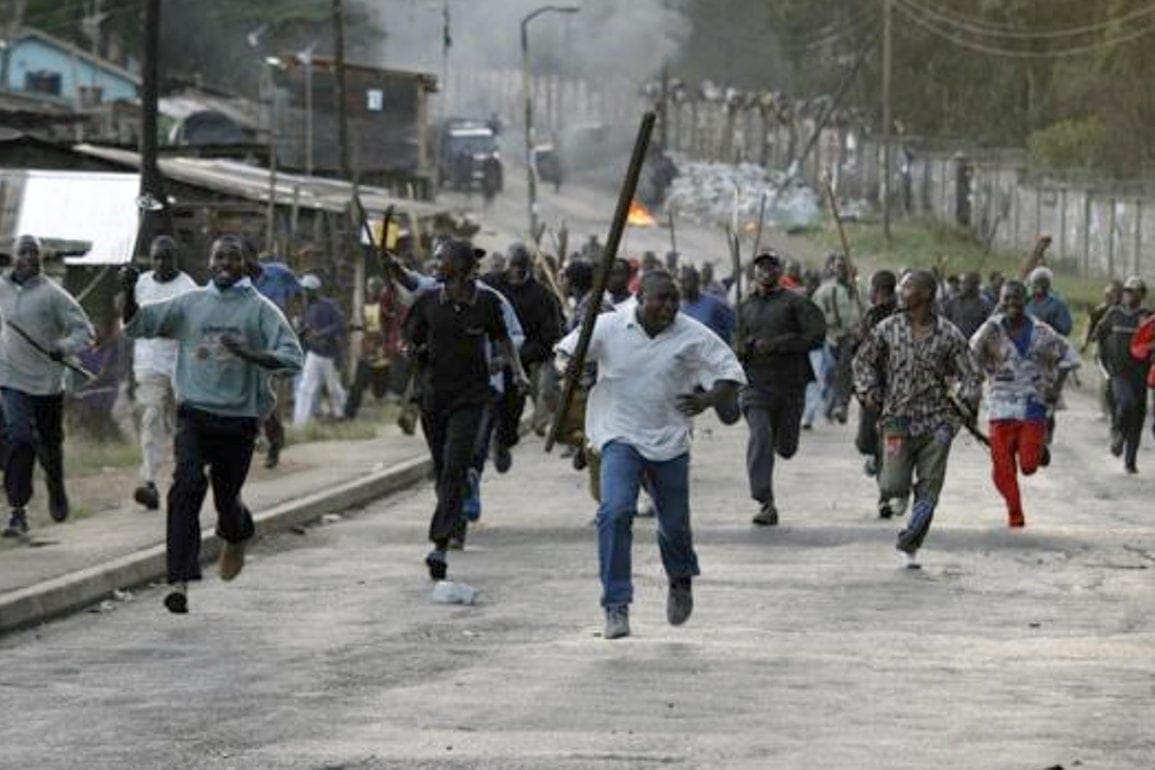

Since that day, I became aware of mothers who saw their children taken just because they live in an at-risk area. If you live in poverty with limited resources, in rural areas, or in dangerous areas, they assume you to be a criminal. The exception regime causes serious collateral damage in communities.

Living with the fear of being captured again

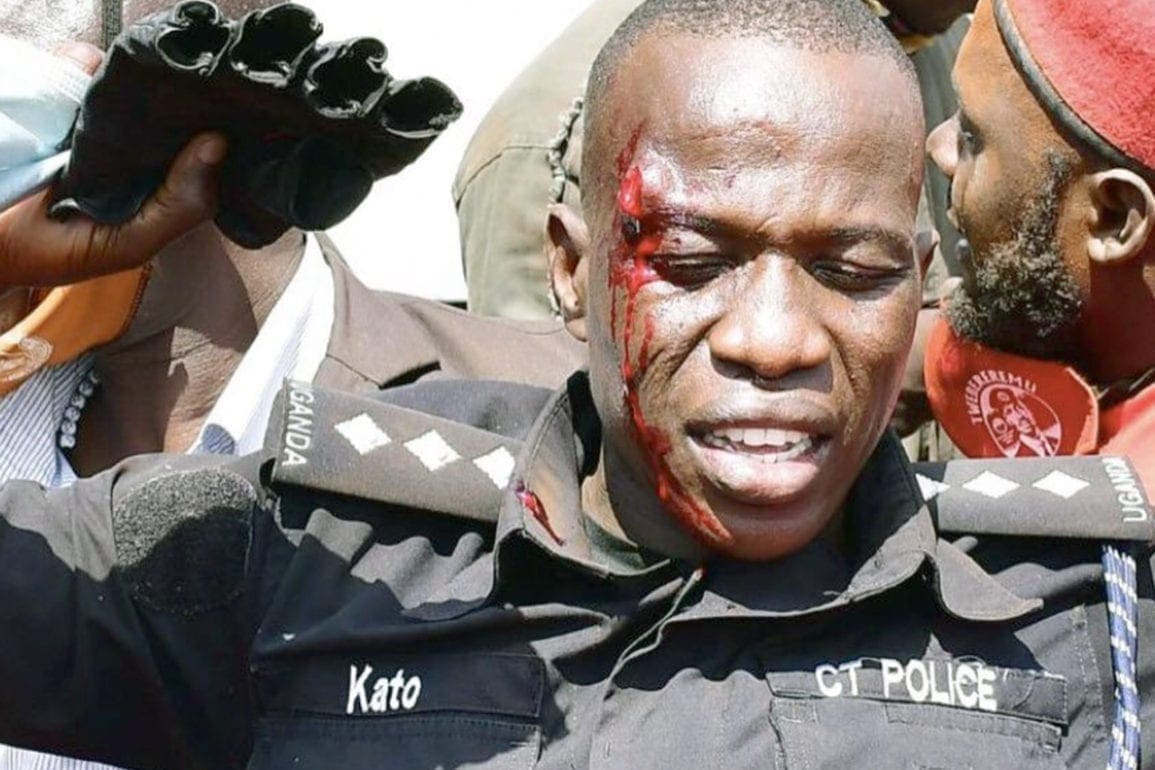

To this day, when I talk about what happened to me, I fear being detained again. The authorities harass and intimidate me. I continue going to college and they even detained me a second time. They stopped me when I went to pick up my younger brother from soccer practice.

Again, they asked if I had tattoos and I showed them, I have none. When they asked if I had been detained before, I said no out of fear. They realized I lied and attacked me, hitting me on the head and calves.

I wanted to leave this country, but my parents’ health will not allow it. We recently received a letter saying my brother would spend another six months in prison pending the investigation. I pray to God, asking that things return to normal.

I hope my brother comes out and can restore his life. It feels difficult to maintain hope, but I believe God will give us the strength to overcome this tragedy.