A choice between two worlds, Russian-Ukrainian woman faces frequent question, “Which side are you on?”

Our whole family remains scattered across the affected areas, some in Kyiv and others in Moscow. Our conversations remain brief. They think carefully about what they say, afraid of facing persecution.

- 2 years ago

March 27, 2024

BUENOS AIRES, Argentina — For two years, a question plagued me: “Whose side am I on?” People often ask, “Are you Russian or Ukrainian? What do you think about the war?” It feels like a difficult question. Born in Moscow during the 1980s, I grew up in the Soviet Union or what we now call “Sovok.”

A decade later, my family moved to Kyiv, and 20 years ago, we made our home Argentina. Nowadays, we run a cozy little hair salon on Jorge Luis Borges Street, smack in the middle of Plaza Italia. Reflecting back on my childhood, I remember people sharing the sense that we were “all in this together.” Now, they assume I must pick a side.

Explore more stories about the Ukraine-Russia conflict At Orato world Media.

A childhood between two countries

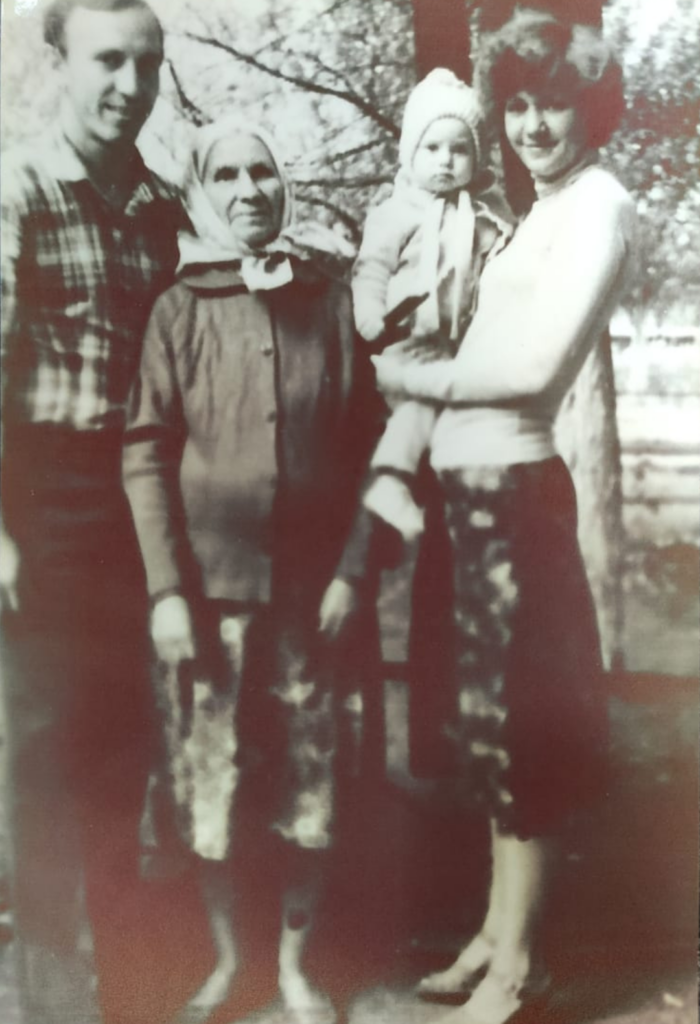

Due to my father’s military career and my grandparent’s diplomatic work, my life intertwined with Russian and Ukraine. While my birth on July 24, 1980, took place in Moscow, my brother Vlad was born in Kyiv and Alex in Siberia.

At six years old, I moved with my grandparents to Kyiv as they sought refuge from the harsh cold and other challenges. They wanted to be in a more favorable environment. At that time, the city remained part of the U.S.S.R. Meanwhile, my parents remained in Siberia to fulfill their military duties.

In 1992, after completing their service, my entire family reunited in Kyiv, just as the Soviet Union dissolved. That’s how I ended up being a Ukrainian citizen, at least on paper. Growing up, I spent summer vacations between Crimea and Makiivka. I remember the happiness I felt reuniting with my dad’s parents, uncles, and cousins. The location never mattered; we felt like neighbors from neighboring lands. I treasured every moment.

When people ask me to pick a side, I think of my grandma from Moscow and my grandpa who is Polish and Ukrainian. How can I claim one place when my uncle in Moscow may end up fighting my uncle in Ukraine? How can my mother choose when her kids come from all over these two countries, which are now at war?

Brothers avoid forced military service, thousands of Ukrainian-Russian households struggle with conflict

In 1998, to keep my brothers from forced military service, my family considered moving to another country. First, we considered Canada, but a problem with our paperwork stopped us. Then, through friends, we heard about a place called Argentina. They described it as a stunning country with a good dollar value and hummingbirds everywhere.

Curious, we began looking into this paradise. We knew about Brazil from the “Do Brazil” fruits. Yet, unlike now, I couldn’t just Google Argentina from my grandma’s house in Kyiv. When we learned of the opportunity to become citizens in five years, we decided Argentina sounded like a good temporary option. If we disliked it, at least we made our way closer to America and Canada.

In 2000, we moved to Buenos Aires without speaking the language and three suitcases in our hands, right after the Menem era. I give my mother credit for her vision. My brothers avoided the military, and we all got a fresh start in a new country.

If we had not moved, my two brothers would be forced to fight each other in the Ukraine war today. This story plays out in thousands of Russian-Ukrainian households around the world. This war is absurd. I don’t belong to any side. I’m from the old Soviet Union, and I love my homeland, feeling pain for both sides. It tears my soul apart.

Family remains scattered from Kyiv to Moscow

Right now, in the area where my grandma lives, only women and children can evacuate. The men must stay and serve their country. My “babulia,” as I lovingly call my grandma in Russian, remains in the conflict zone. At her age, she has little strength to run away. It breaks my heart to think of her living through another war. She survived World War II as a child. Similarly, my father, like many other Ukrainians, stayed to protect what little they have left.

Our whole family remains scattered across the affected areas, some in Kyiv and others in Moscow. Our conversations remain brief. They think carefully about what they say, afraid of facing persecution. When I talk to my dad, I ask, “Do you want to send me a photo or tell me something?” He always replies, “No.” He lacks trust in the situation and kindly reminds me, “Better not to talk because things are so uncertain.”

They remain, even now, in fear and shock. Often, when I show them photos from television here, they say, “Imagine what we are going through.” Living in Buenos Aires, I feel haunted by the constant fear of not knowing whether my family in Ukraine will be alive when I wake up. If my uncle Dima, who lives in Moscow with his Russian wife and kids, wanted to go back to Kyiv today, he would have to do it alone in the face of danger.

Children should not be learning war tactics, they should play and go to school

My best friend escaped from Bucha to France after hiding for over a month in a basement with her five- and six-year-old children. She told me they learned to differentiate the sounds of gunfire and determine its distance from their hiding place.

As a mom, it breaks my heart these kids learn war tactics instead of attending school or playing. Every morning, as I prepare my own daughter for class, I feel grateful to be safe and far from the conflict. This stark contrast to the reality so many others face weighs heavily on me every day.

These thoughts elicit flashbacks. I remember training for war in school during my childhood. We had military preparation and first aid classes once or twice a week. They taught us how to move in coordinated groups, find our way through dark places like forests, light fires, and other survival skills. It became a required part of our school curriculum.

The bombings in Kyiv hit me hard, tearing away pieces of me with each place Russia destroyed. Memories and stories vanish. It feels like I am being slowly dissected. Yet, I know I am better off than those in Ukraine, with my normal routine in Argentina. Still, I cannot blot out the news pouring forth from my origins in Eastern Europe. Even while standing in the hair salon with the music playing from the television, my heart and mind remain on the front line. The unfolding humanitarian tragedy exceeds words.