Political prisoner recalls two years in the dungeon of a solitary cell at a maximum-security prison in Zimbabwe

After the search, I ate my Sadza and within minutes, my stomach burned and became irritated. That night, sleep alluded me and I began vomiting. Blood appeared in my stool, so I called the prison officers, but no one responded.

- 2 years ago

April 20, 2024

HARARE, Zimbabwe — For nearly two years, I endured confinement in a solitary cell, a mere two-by-one meters in size. Alone in that cramped space, I felt cut off from the outside world, deliberately isolated and discriminated against by the authorities in Zimbabwe. They threw me into prison, not for a crime I committed, but for political reasons.

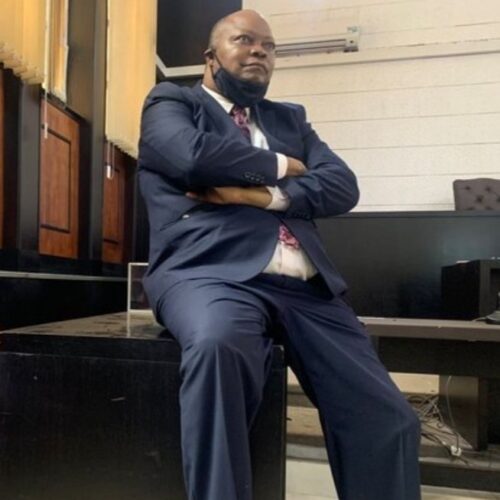

As a lawyer representing a victim of a politically motivated murder, I suddenly became a target of the very people I opposed. My arrest and detention became part of a broader agenda to eliminate me from the electoral process in Zimbabwe last year [which has been documented by the media]. Those in power sought to sideline key players like me to prevent a free and fair election. My imprisonment serves political interests, not justice. It feels like complete disregard for the legal standards governing imprisonment in Zimbabwe.

Read more stories out of Zimbabwe at Orato World Media.

Denied visitors, man fears for his safety

Like anyone placed in the hands of strangers, during my imprisonment, I made every effort to remain completely alert. As the days passed, friends and relatives came to see me, only to be turned away by the authorities. The prison staff refused to allow my relatives to bring me food [a benefit other prisoners enjoyed].

When it came time for court appearances, the officers forbade me from greeting friends and relatives in the courtroom, creating a bizarre atmosphere. When one prison guard treated me in a friendly manner, I asked him, “Why do I receive no visitors except for my wife?” After all, I held a senior position in my political party and had friends around the country.

The officer told me that the authorities dismissed people who came to see me, and that around 10 to 12 people came every day. A week later, my lawyers finally received access. They told me they experienced the same thing. While my lawyers worked on the issue of receiving visitors, the prison continued to permit few people in.

As a result, I could not rely on interactions with others to escape my thoughts. I needed to endure my time in prison and learn survival tactics. All the while, despite having contact with my legal team, I feared my government’s ill intentions and suspected an attempted poisoning twice after cell searches.

Prisoner suspects attempted poisoning

One day, the guards came and opened my cell. They took me outside while a team of officers began searching my room. When I inquired about the reason for the search, they offered no satisfactory answer, saying only that they were “looking for something.” Being held in solitary confinement, I had no ability to bring anything in from the outside without their knowledge.

Therefore, when my wife brought food one day, they allowed it. I ate some and left the rest to eat later. After the search, I ate my Sadza and within minutes, my stomach burned and became irritated. That night, sleep alluded me and I began vomiting. Blood appeared in my stool, so I called the prison officers, but no one responded.

The following day, they denied me a visit to the clinic. When my lawyer visited, I explained the circumstances. After a struggle to see the prison doctor, the guards finally allowed it. The process seemed flawed, and I felt they would deny me a truthful diagnosis, so we insisted on seeing a private doctor. To this day, I remain concerned about my health condition, as I never received a true medical examination. Locked inside my cell for 17 hours a day, I enjoyed limited outdoor time. When electricity became available, I read, and when I could, I exercised to maintain my fitness.

Thousands of people wait for political prisoner at his home

After 585 days of pre-trial imprisonment, the authorities finally released me. I walked out feeling abused, unaware of a valid reason for my incarceration since the beginning. It seemed those against me achieved their ends through the abuse and use of national institutions.

“These institutions should never be the forum to solve political disputes,” I thought. By then, I became used to the prison walls and courtrooms. Each time I went to court, the gallery remained packed with hundreds of people singing songs of encouragement and calling for my release.

On the day I finally walked out, once again, I saw a packed gallery but could not imagine what awaited me two hours later. At home, a huge mass of thousands of people gathered, awaiting my arrival. I could hardly get inside. As I made my way in, I greeted leaders active in the struggle for Zimbabwe’s democracy and shook hands. I wanted to cry but felt an inner strength calling me to speak.

I felt the masses of people needed some consolation from me. After being in prison, it felt as if I found my real self again in the joy of meeting people and breathing fresh air. It was a good night. That day, one of the prison officers said to me, “We don’t want to see you anymore. Please move out.” I believe they felt some pressure, since the courts required my immediate release, yet they still needed me to meet their ends.

After release, political prisoner faces loss of work and rebuilding his practice

When the final judgement came, the courts convicted me and sentenced me to three years in prison, wholly suspended for five years, leaving me with a two-year sentence. Under the Prison Act, when an accused person is convicted and given a sentence, there is remission where about one-third of an individual’s prison sentence is reduced. This means I had 13 months serve, but I’d already been in prison for 20 months.

It felt strange to know that I served more time than my actually sentencing in the case – a complete violation of my rights. In that moment, I felt a deep pain inside of me. I considered the precious moments I lost while in prison. It became impossible not to shed a tear.

Reuniting with my family and my community proves challenging since my release. As a lawyer, I enjoyed a thriving practice before I went to jail. I came home to find everything at a standstill. Throughout my imprisonment, my family relied on the support of friends and well-wishers. This would have been an unthinkable situation before.

Today, we are starting from scratch in an attempt to rebuild what we lost.