Photojournalist captures iconic image of Filipino fishing boat eclipsed by Chinese Coast Guard vessel at the disputed Scarborough Shoal

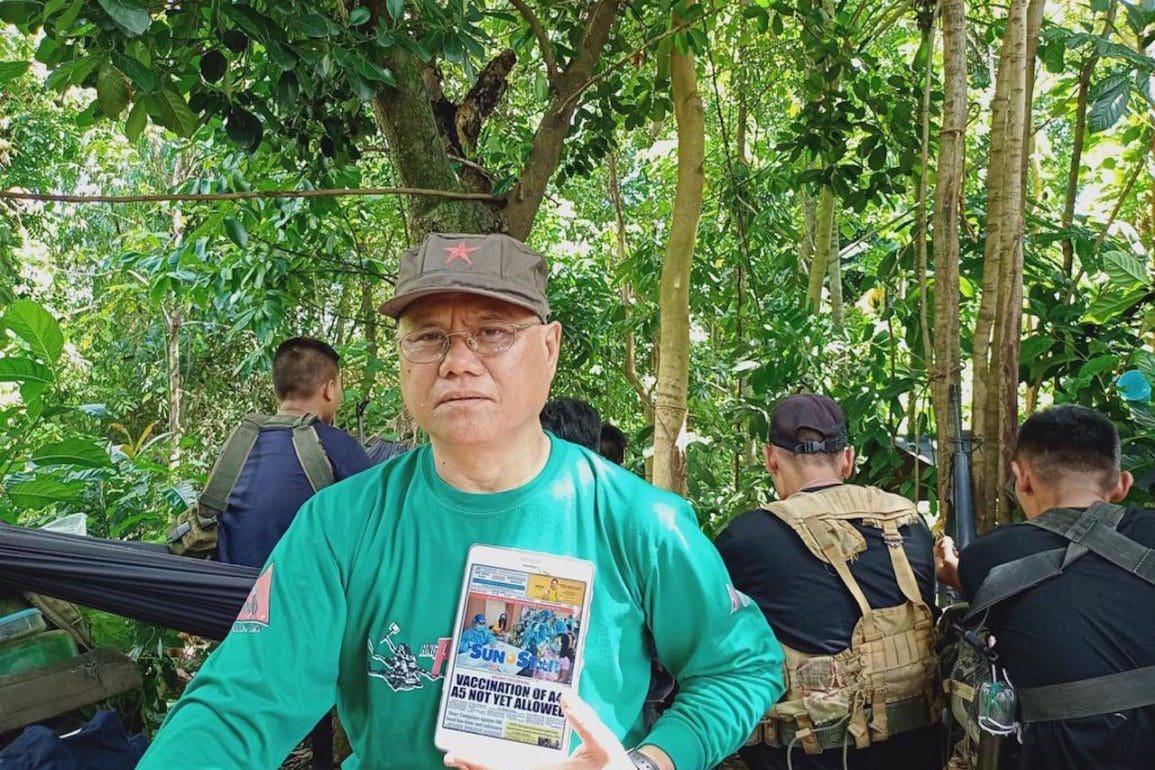

We climbed into the bangka or the small fisherman’s boats. We placed one reporter on each boat posing as a fisherman. Wearing a fisherman’s hat, we kept our cameras hidden in our cloaks. By the time we set out, it was late afternoon – 4:00 or 5:00 p.m. We approached the Scarborough Shoal at the vast open mouth of the lagoon.

- 1 year ago

September 17, 2024

WEST PHILIPPINE SEA, Philippines ꟷ From the moment the Chinese began occupying the West Philippine Sea (WPS), the region became a hot topic. Everyone saw and heard the footage on the news. Since then, however, the media coverage died down. As a photojournalist, I felt a strong urge to go there. I waited for months for the opportunity to arise. When the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR) invited me to join their resupply mission to the West Philippine Sea, along with other media representatives, I felt happy and excited.

Related story: Outlaw Ocean Project investigates murder and abuse on Chinese squid vessels

Photojournalist witnesses Chinese Coast Guard vessels stationed in the Scarborough Shoal 124 miles from the Philippines

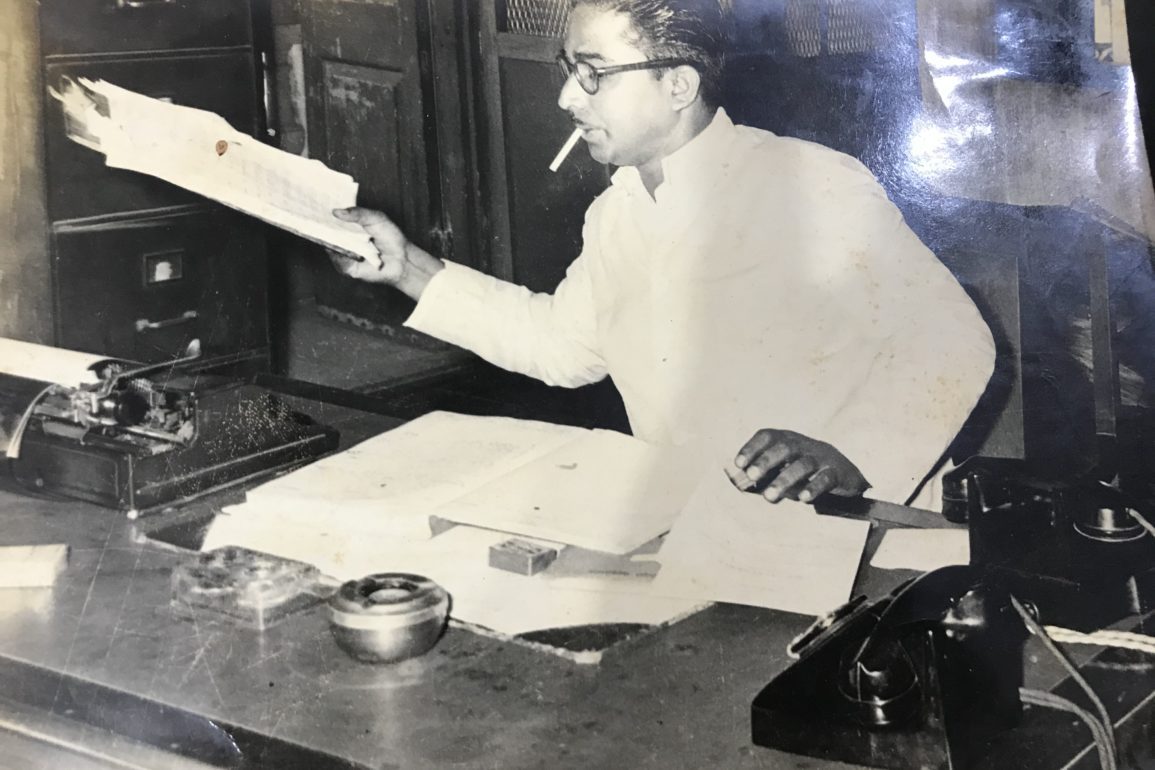

Typically, authorities limit the members of media who can cover and report on the situation in the West Philippine Sea. When an opportunity arises, they allow only a handful of journalists to go in. When I received the invitation to join BFAR, I finally had an opportunity to take photos. Telling a story through photojournalism, as opposed to traditional written journalism, produces very different results.

When we arrived at our departure location, I saw about 10 bangka [small wooden boats] for each mother boat. Approximately 40 mother boats gathered to make the trip to the infamous Scarborough Shoal.

[The Scarborough Shoal “is one of Asia’s most contested maritime features…” One hundred and twenty-four miles “off the Philippines and inside its exclusive economic zone, the shoal is coveted for its bountiful fish stocks…” A 2016 ruling by the Permanent Court of Arbitration largely favored the Philippines and ruled that China’s blockade violated international law. Yet, the problem persists.]

The 40 mother boats provided the necessary space to carry our gasoline supply and food packs. On the boats, as we neared our destination, everything felt normal and relaxed. At first, we did not see any Chinese Coast Guard ships on site. However, the moment they appeared, I felt the tension build. They began to radio us issuing challenges and the exchange went back and forth. Like a volley, they insisted on having the right to be in the shoal, and our people said the same. Suddenly, things took a turn when they began to tail us, leading to dangerous maneuvers.

Chinese Coast Guard sets floating barriers to prevent Filipino fisherman from entering the Scarborough Shoal

In the Philippines, there is a game where you block the runner from trying to cross to the other side. That day, in the Scarborough Shoal, it felt like a game of patintero. I felt safe during the commotion, but for an ordinary citizen, it would have felt very intense. The chasing, blocking, and evasive maneuvers played out, and we made it through the first morning in the shoal.

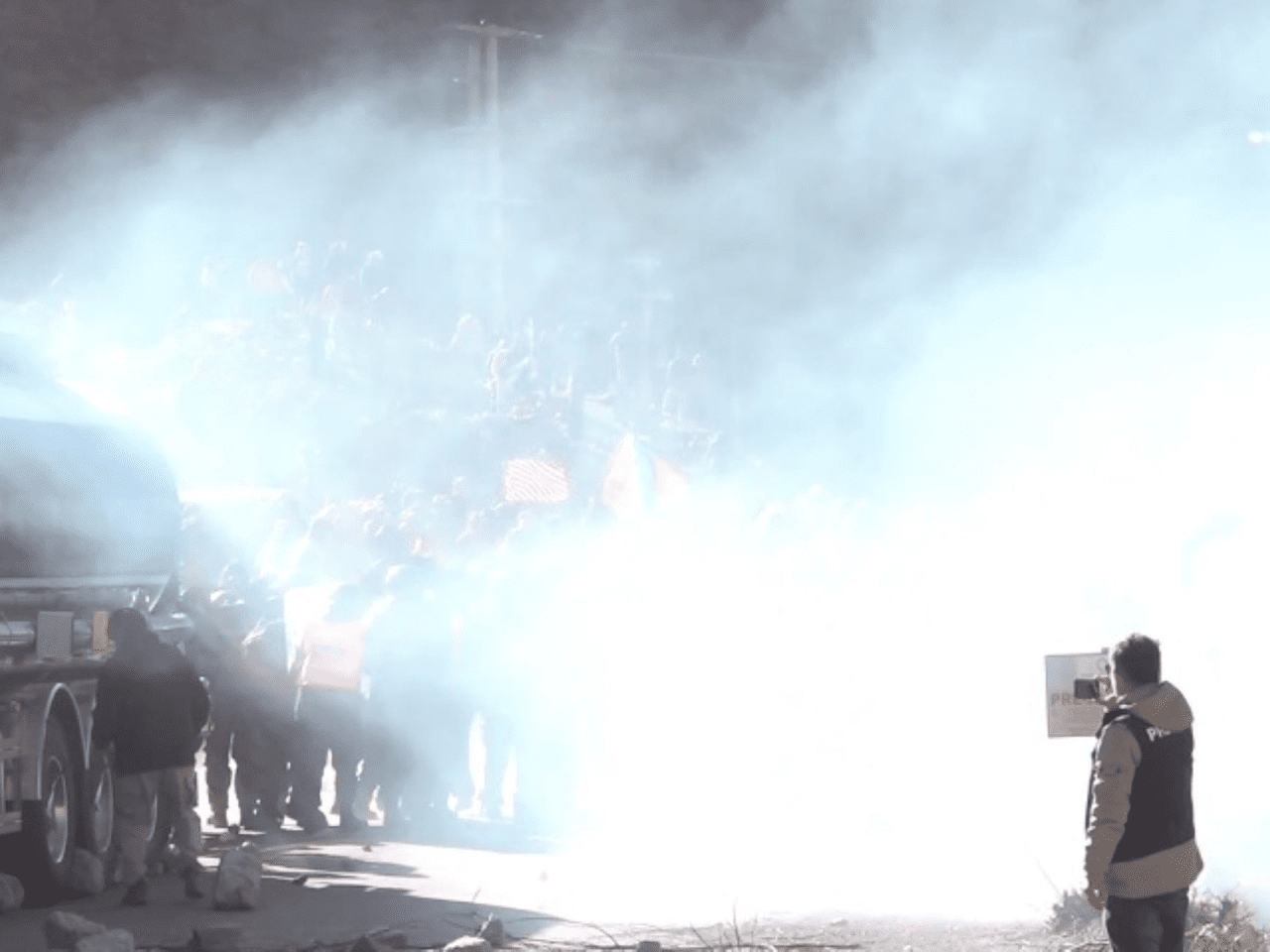

Videos exist where the CCG rams Filipino boats, but we experienced no physical contact. I took solace in the fact that if anything happened, the BFAR’s plane patrolled nearby and the Filipino authorities were a phone call away. By afternoon, the Chinese began placing floating barriers in the water. As a photojournalist, I felt the urge to get near it before it was too late. From far away, I feared taking poor pictures.

The situation proved risky. We faced the danger of the CCG seeing our Philippine Coast Guard boat. Instead, we climbed into the bangka or the small fisherman’s boats. We placed one reporter on each boat posing as a fisherman. Wearing a fisherman’s hat, we kept our cameras hidden in our cloaks. By the time we set out, it was late afternoon – 4:00 or 5:00 p.m. We approached the Scarborough Shoal at the vast open mouth of the lagoon. Seeing the floating barriers, I wanted to take as many pictures as possible. “This opportunity may not arise again,” I thought.

I snapped some pictures and wanted to take more but the CCG began showing up behind us. Once they see you, they can make it to your boat in a minute or less. I knew they could overcome us at any time. When we saw them for the second time, we hurriedly took photos, before stopping for the day.

Iconic photo of Chinese Coast Guard vessels eclipsing a Filipino fishing boat makes headlines

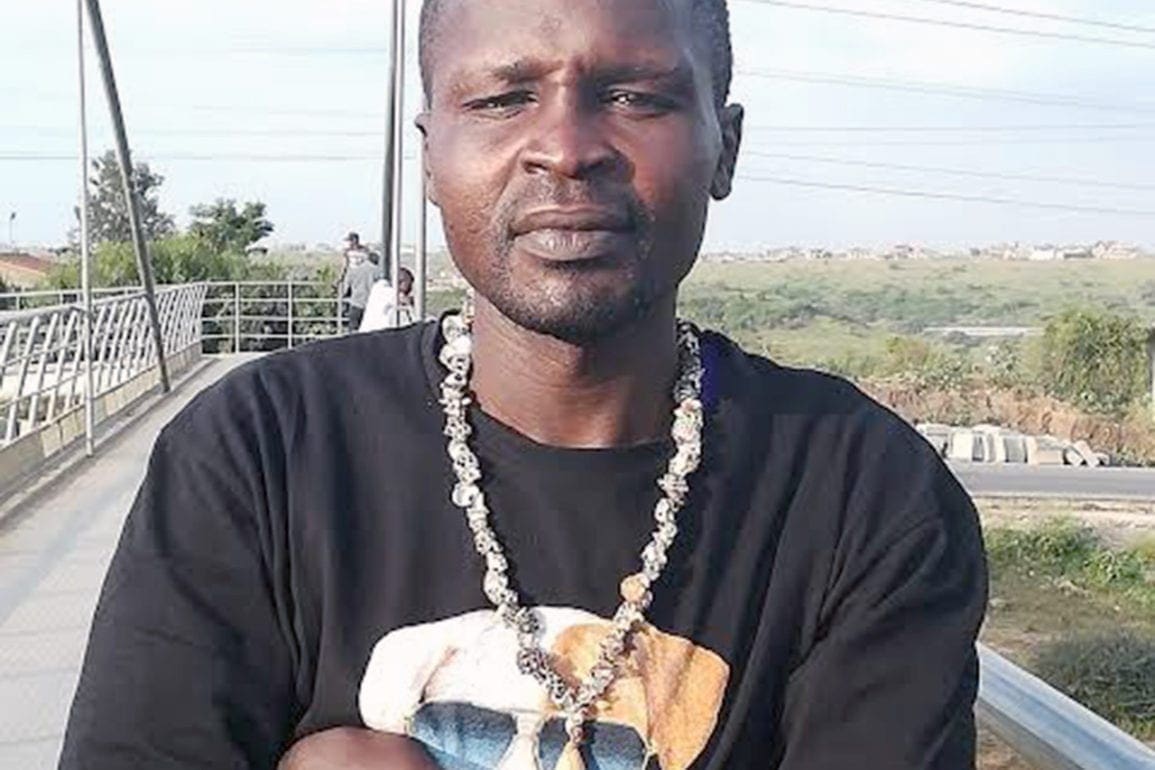

The next day, we returned to the shoal but for two nights, we could not get through. About to pack up and leave, on the last day, we approach the shoal. Heavily guarded by the CCG, a fisherman named Arnel Satam attempted to enter the lagoon as I sat on a fishing boat. Three CCG boats prevented his entrance and the atmosphere felt different somehow.

As the CCG attempted to near us, I felt a surge of patriotism. “This is our territory,” I thought. I felt the tension building and, in my mind, I said, “Let’s get it on.” I felt this vibe of wanting to defeat the ships coming toward us. The Chinese brought out their water cannons and in response, the PCG brought out theirs.

Everyone seemed ready to rock and roll when, suddenly, Arnel attempted to get through in his fishing boat. The chase was on. The CCG chased Arnel down. In that moment, I wished I had my drone. The action proved too good not to capture. Eventually, Arnel made his way back to us and the chase ended. Luckily, along the way, he passed by two big CCG boats, creating the perfect frame for my picture.

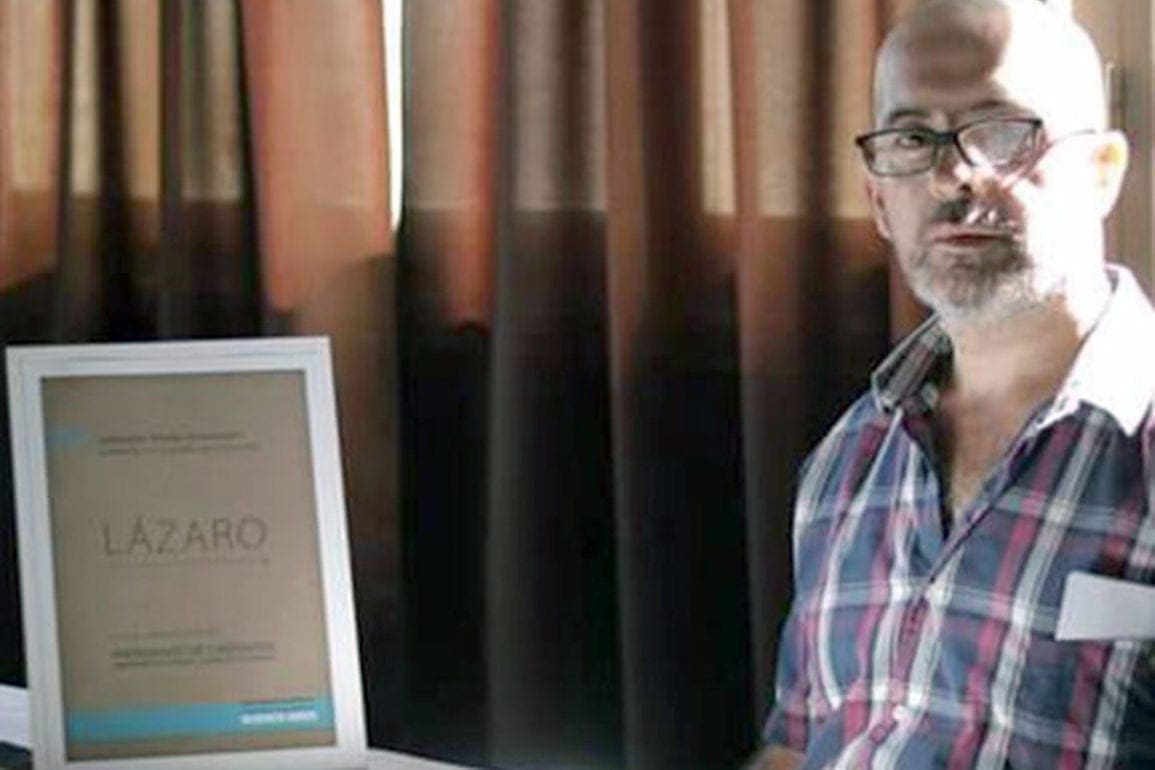

In that scene, you see the Filipino fishing boat in front of two massive Chinese Coast Guard boats. I hurried to the other side of my boat to catch the image. A camera crew did the same, but one of them tripped on the way. I made it to the edge and captured the symbolic shot. [Varcas’ project Battle for Sovereignty subsequently won a regional prize in the 2024 World Press Photo Contest.]

After winning world photo award, man thinks of the fishermen at the Scarborough Shoal

As a photojournalist, I give it my best, but the job remains challenging and economically taxing. In this age of social media where people’s attention spans shrink, it often steals the spotlight from mass media. Yet, the photos we take last forever. They go beyond the hot topic or current news headlines. These photos become part of history. They transcend the fleeting popularity of a particular platform.

In my profession, I attempt to make that point by doing my job right. Some think, these are just photos. They generate no income for the news company. I say we must place importance on these photographs. To the photographer, taking a great picture offers more than recognition. We take risks. We face injury and work hard for every photo we capture. For readers, audiences, and the public interest, I give of myself to my full capacity.

When I learned that I won the regional prize in the 2024 World Press Photo Contest, I felt overjoyed. The award had not been announced publicly yet, and some preparations needed to take place. I enjoyed the win for months before the announcement. When the news went public, my phone rang incessantly. Driving at the time of the announcement, I was enjoying the road when a wave of calls and messages came in.

In that moment, my hard work paid off and not just for personal recognition. I thought of the fisherman at the Scarborough Shoal. “This is for you,” I thought. “This is your story and we put a spotlight on it, so the world would know.” I feel happy I did it for them, and I can count this bonus as a landmark in my career. The Scarborough Shoal is our territory, and I did this for my country.