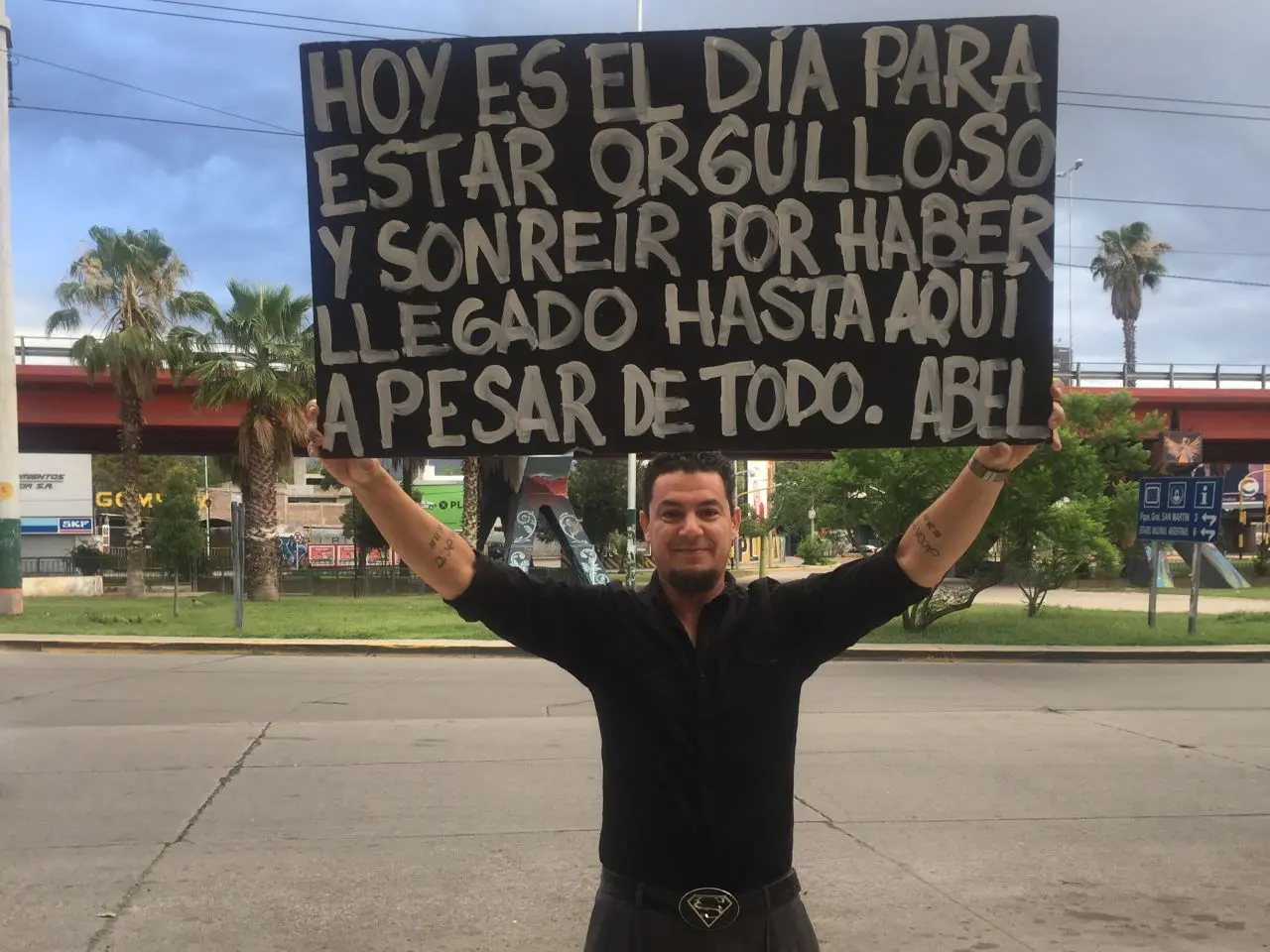

The face of the water crisis decimating Uruguayan civilians

The desperation feels like a palpable presence in the air. Jugs disappear from supermarkets and their absence spreads. Now a two-hour drive out of the city yields no supply. We come up empty handed. Long lines form and a spark of hope ensues. “There must be supply,” we think. Then the dream shatters in minutes. The limit of two free jugs barely even covers drinking and cooking.

- 3 years ago

July 18, 2023

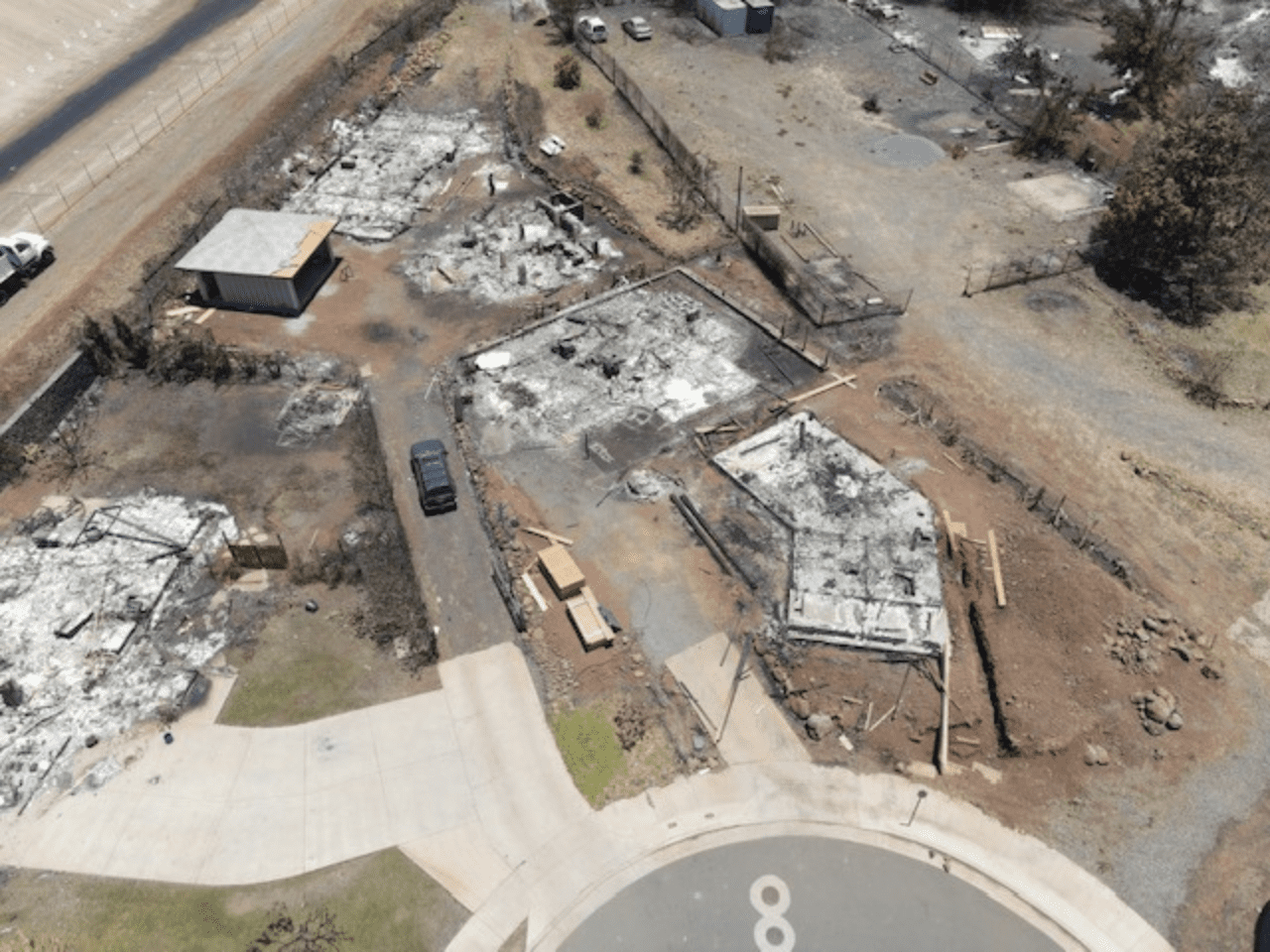

MONTEVIDEO, Uruguay ꟷ As the city and surrounding region face an unprecedented decline in freshwater reserves, the evidence of the water crisis in Uruguay unfolds before my eyes. Shelves sit empty where water jugs used to be. Our main source of freshwater – the Paso Severino Dam – hovers on the brink of exhaustion. In a desperate attempt, authorities mix water from the Santa Lucía River with water from the Río de la Plata to meet the people’s daily needs. Now, saltwater flows from the taps.

If the rain does not come soon, or if aid does not arrive, we face little respite. Any escalation of this crisis will make it the worst water shortage in our history. The relentless drought takes its toll as fear escalates. “What if the water from the taps ceases,” we worry.

Read more environmental stories from Orato World Media.

Strained budgets and lack of supply leaves us desperate

In the face of this crisis, uncertainty looms large. I feel the effect of the physical and emotional hardship as I watch my neighbors struggle to secure safe water. The solution – utilizing saltwater containing alarming levels of chloride and sodium – has health professionals sounding alarm bells.

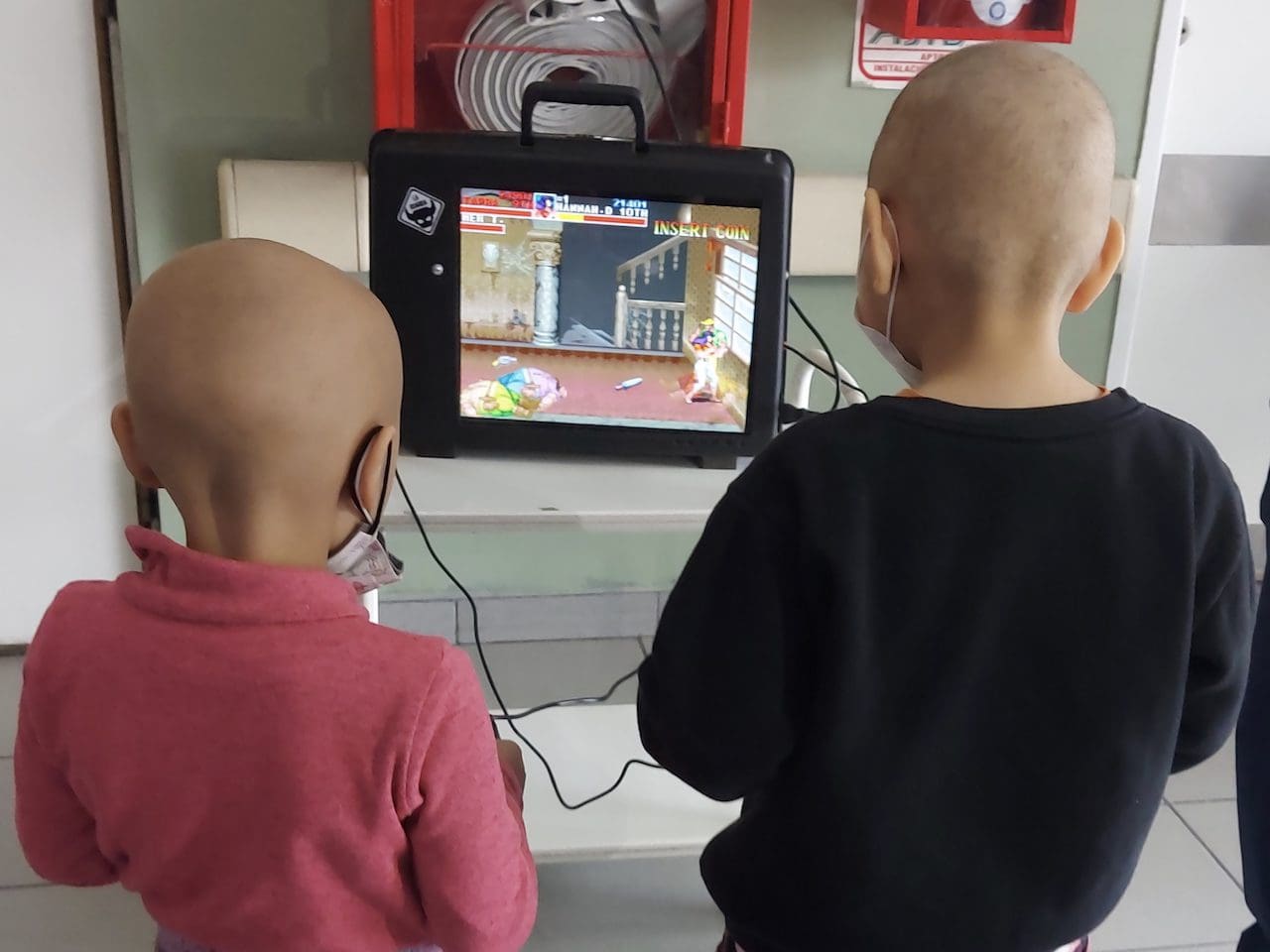

To make matters worse, studies reveal an increase in trihalomethane – a compound that forms when water is disinfected. Some studies say it causes cancer. The consequences become evident. I hear the reports of escalating health issues like hypertension, kidney problems, and other effects of consuming brackish water. We feel nothing short of desperation.

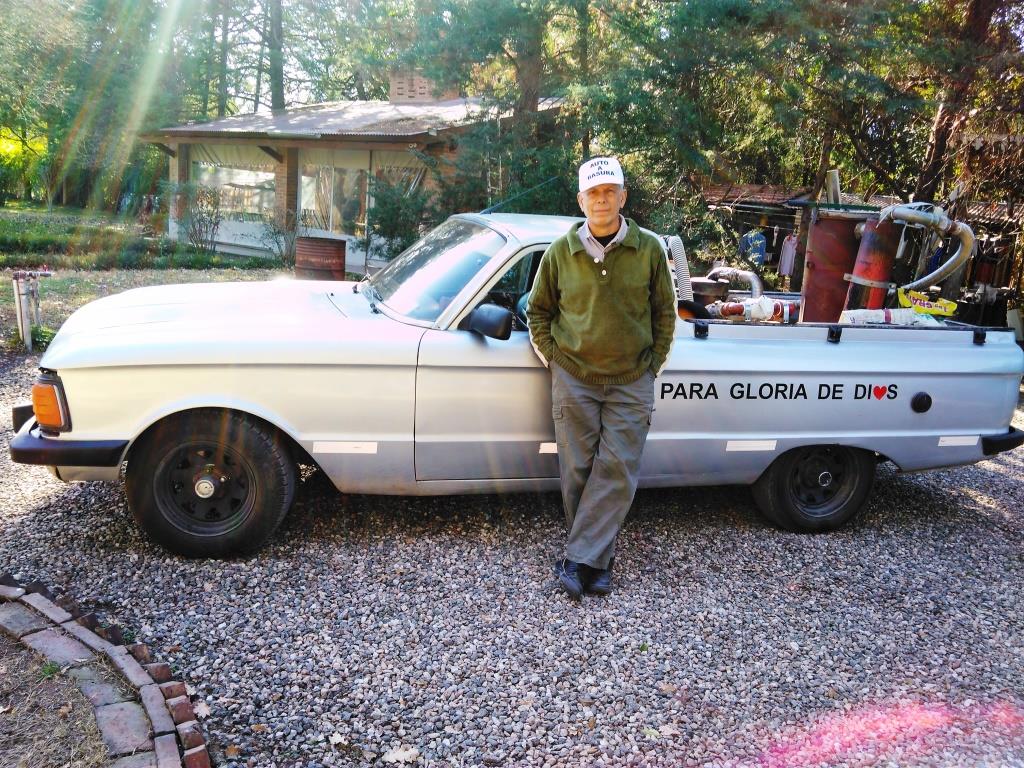

As I walk through the streets of the city center, I see people carrying barrels. They become the embodiment of struggle. Restricted to purchasing a maximum of two six-liter bottles per person compels us to rely on barrels. While tax cuts reduced the price of bottled water, a jerrycan [typically five gallons] can cost up to 89 pesos [just over two dollars]. Paying for water like this to meet every need of the family strains already stretched budgets.

The desperation feels like a palpable presence in the air. Jugs disappear from supermarkets and their absence spreads. Now a two-hour drive out of the city yields no supply. We come up empty handed. Long lines form and a spark of hope ensues. “There must be supply,” we think. Then the dream shatters in minutes. The limit of two free jugs barely even covers drinking and cooking.

Despite last month’s announcement of a Water Emergency Fund, aid fails to reach the most underprivileged and hope grows dim.

When will we have a voice? The system is failing

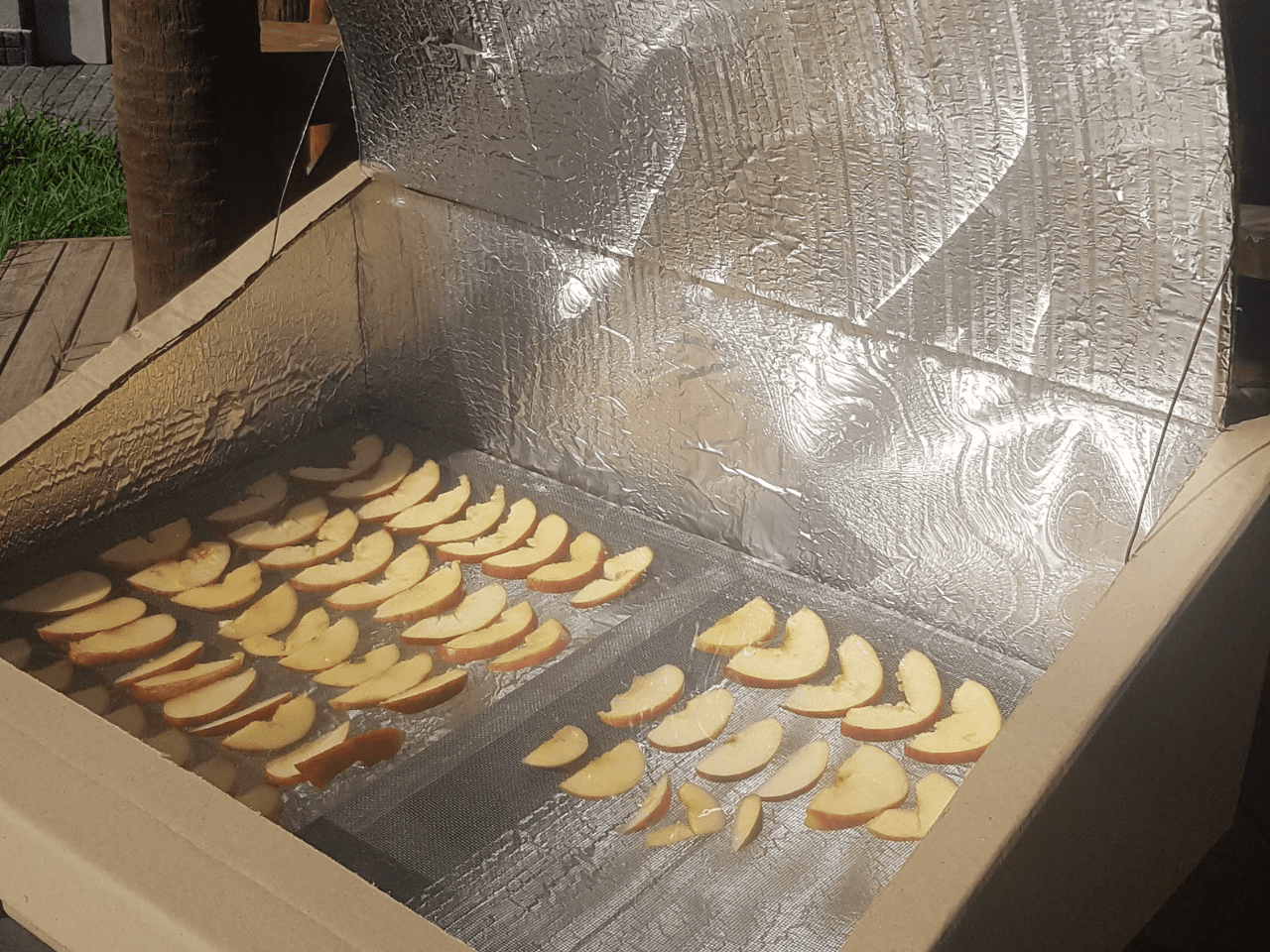

I fear using tap water, and like so many around me, restrict its use. With known contaminants, I don’t want to cook with or bathe in it. We fear killing our plants and harming our pets, so some of us rely on mineral water. Every single day, I go out and purchase four or five liters of mineral water to try and meet my needs.

As I bleed money purchasing water, I continue to receive regular water bills with no cost reduction. It feels terrible. My heart aches as I stand in long lines only to get to the front and see no water left on the shelves. What must this be like for pregnant women, marginalized people, and individuals with no transportation?

The saltwater flowing through our taps eats away at everything, corroding electrical appliances. Water heaters and hot water tanks fail all around us. I notice the diminishing supply of fruits and vegetables and the rising prices as farmers struggle with the same problem we have in the cities. The message from the authorities reaches my ears: Do not shower. Limit water for bathing. My mind wanders to the children and the babies.

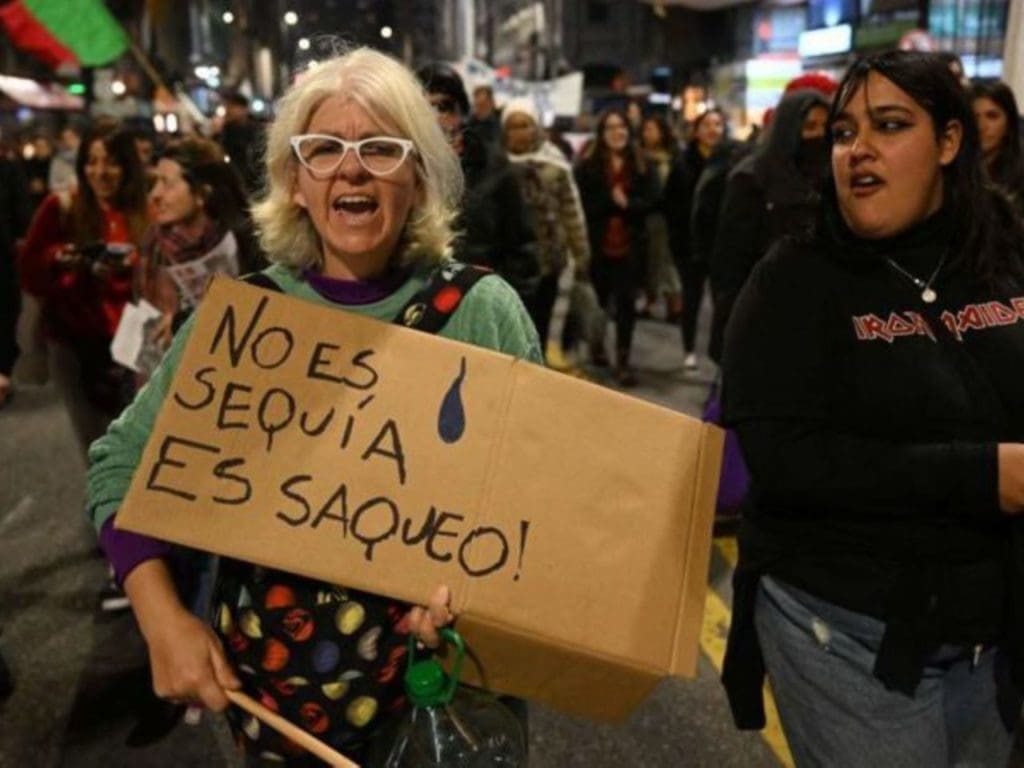

I wonder when I might have a chance to speak out. Perhaps it will only be with my vote in the next election. This goes beyond a lack of rain. It reflects a lack of preparation, a poor model of production, and the consequence of political decision making.