Displaced indigenous community living in Bogotá park demand basic rights, security

We have endured many days eating only lentils and rice. To evade the cold, we sleep piled up, like pigs, under plastic. The children often wake up crying.

- 4 years ago

April 6, 2022

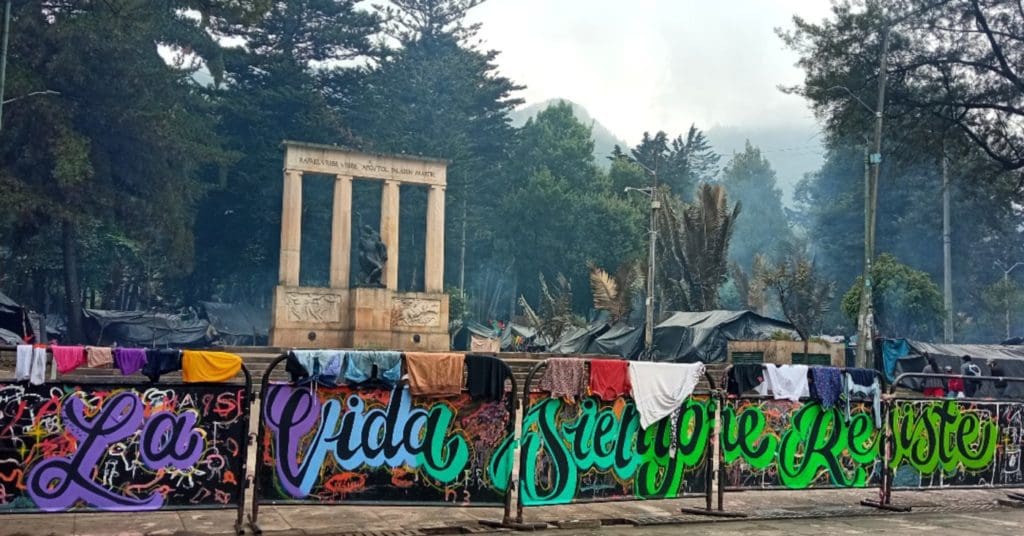

BOGOTÁ, Colombia—I left my land six years ago, threatened by the armed groups there. I cannot return—they will kill me. There are no safety guarantees, even after all these years. Now, my family and I live in makeshift shelters in Bogotá National Park, waiting for the government to provide the protections we need to return to our homes.

We left our territories due to armed conflict and violence between the government and guerrillas and paramilitary groups and will not withdraw from this park until the national government fulfills its promises of security, housing, employment, education, and health. We are not going to vacate until they guarantee us decent living conditions.

The national government and the mayor of Bogotá have to understand that the danger still persists. We have nowhere else to go until we can return and live secure lives where we came from.

One more displaced person in a country of displaced people

Prior to moving into the park in September 2021, I lived in the Santa Fé neighborhood, one of the most dangerous in Bogotá. We lived in a room in what is known as pagadiarios: old, abandoned mansions that are in crumbling and unsanitary conditions. However, I sometimes couldn’t raise the money to pay for the room, and that’s why we came to the park.

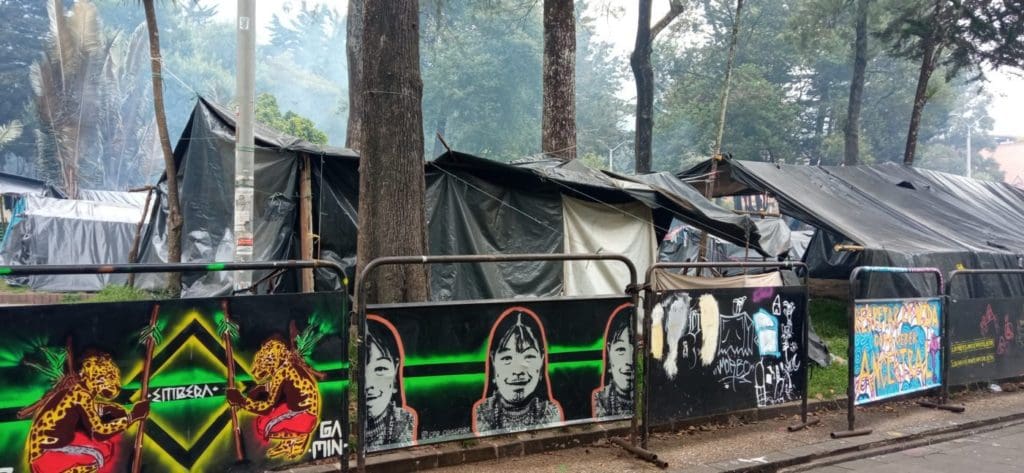

More than 1,300 of us live in the park; about half are children. We live in informal tent-like shelters, or cambuches, in the park, and some do not even have that for protection.

It is so cold here, with temperatures that dip below freezing in the mornings, and it rains a lot—we struggle to protect our families from the elements. The climate is harsh and hard to endure as an adult, and even harder for children and babies. Some of them have been hospitalized due to the harsh weather conditions.

Those of us who belonging to a permanent minga, or a group collectively advocating for their communities and indigenous rights, belong to 13 indigenous peoples, with 13 different languages. Most of them do not speak Spanish and none of them have anywhere else to go, nor the money to obtain more permanent or healthier housing.

Without food, housing, and decent conditions

We have endured many days with only lentils and rice to eat, and many others with rice alone. Adults and children are losing weight. Some passers-by and neighbors give us clothes and food, but it’s not enough. The government gives us nothing.

Too many days, we can’t find a market for our handicrafts or opportunities to work, and that’s when we have to beg on the street.

Each family cooks in their cambuche and collects firewood and water. To evade the cold, we sleep piled up, like pigs, under plastic. The children often wake up crying.

The Colombian Family Welfare Institute comes almost daily to weigh the children and give those who are underweight flour as a food supplement. Sometimes the Ministry of Health arrives with ambulances. That’s the only institutional support we receive.

Seeking a dignified life

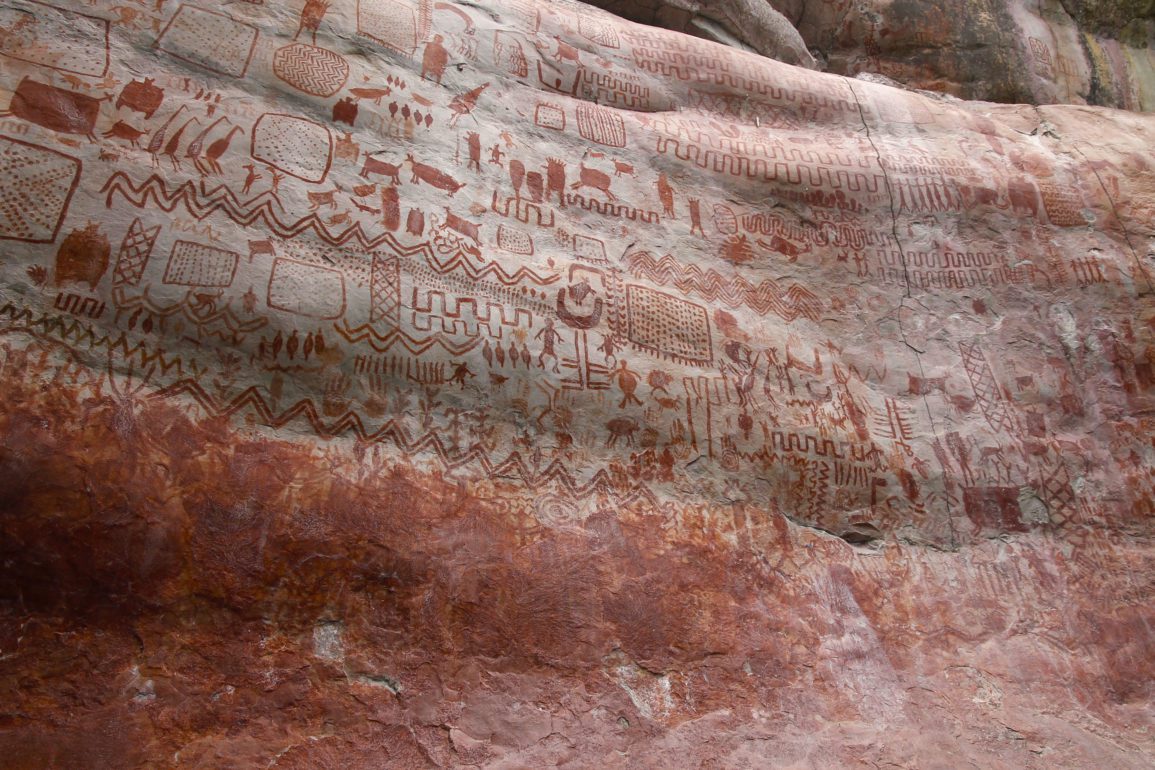

The government discriminates against us, a prejudice we have experienced since colonial times when the Spanish came to loot us. Nothing has changed since then; we are second-class citizens. They have killed us, stolen our gold, and taken our land. We even feel discriminated against by other indigenous people and indigenous organizations.

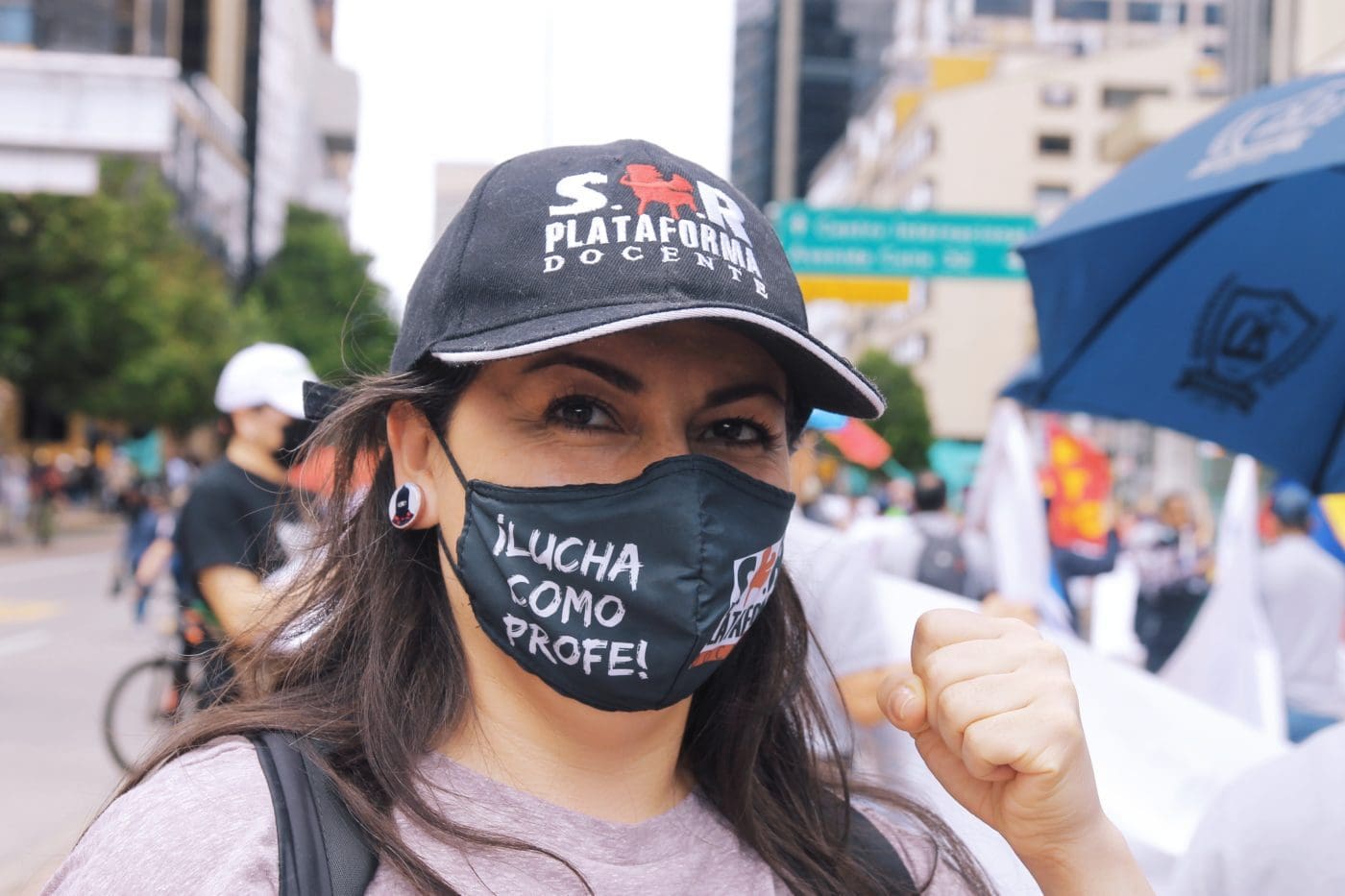

We are going to continue pressing the government until it fulfills our right to a dignified life.

Our group has requested several times for the mayor of Bogotá, Claudia López, to give us an audience, but she has not shown her face—instead, she sends us to uninformed delegates who cannot establish commitments or the Mobile Anti-Riot Squad (ESMAD). We have not received anything from the district administration, only pressure to return to our reservations.

However, we do not want more massacres, more violence, more discrimination. We cannot return until our safety and ability to provide for ourselves is guaranteed.