Guatemalan environmental journalist persecuted for seven years finally free, escapes to Europe

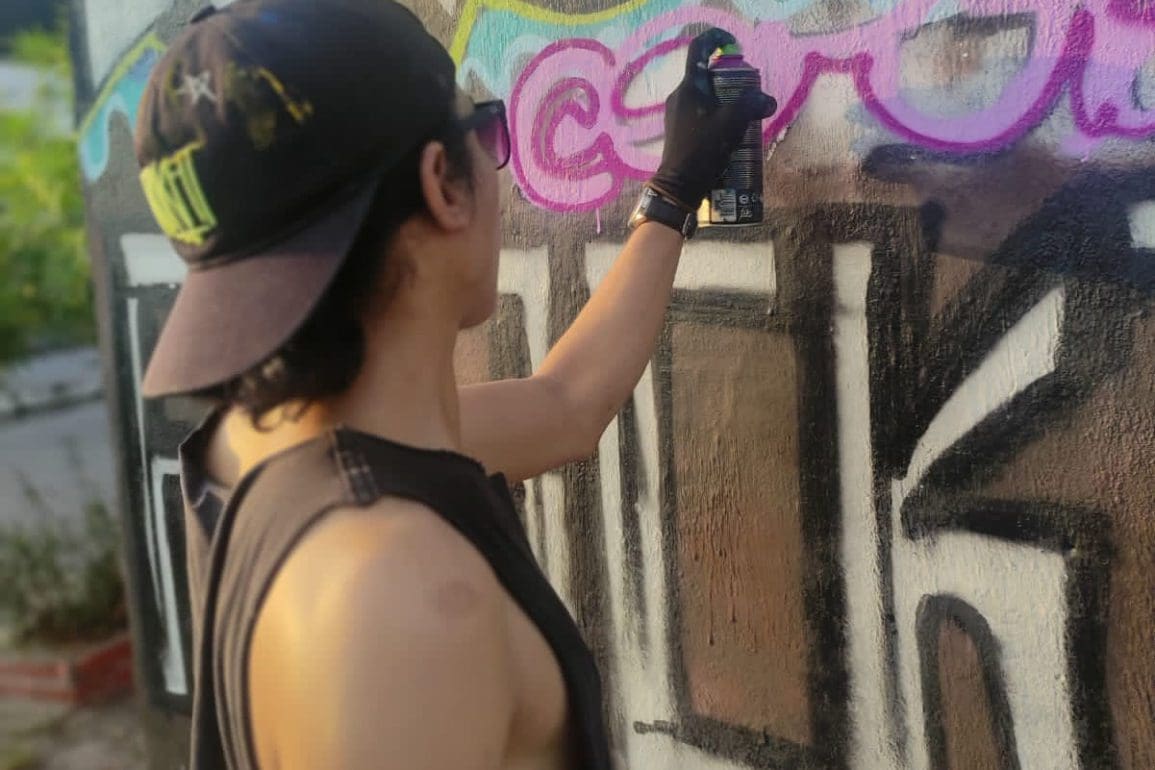

I felt like a prisoner but also recognized the power of my role as a journalist. I needed to tell the stories of contamination, murder, and persecution happening in my region. Some colleagues doubted me, seeing me as an activist rather than a journalist. Online harassment and accusations often plunged me into despair.

- 2 years ago

August 13, 2024

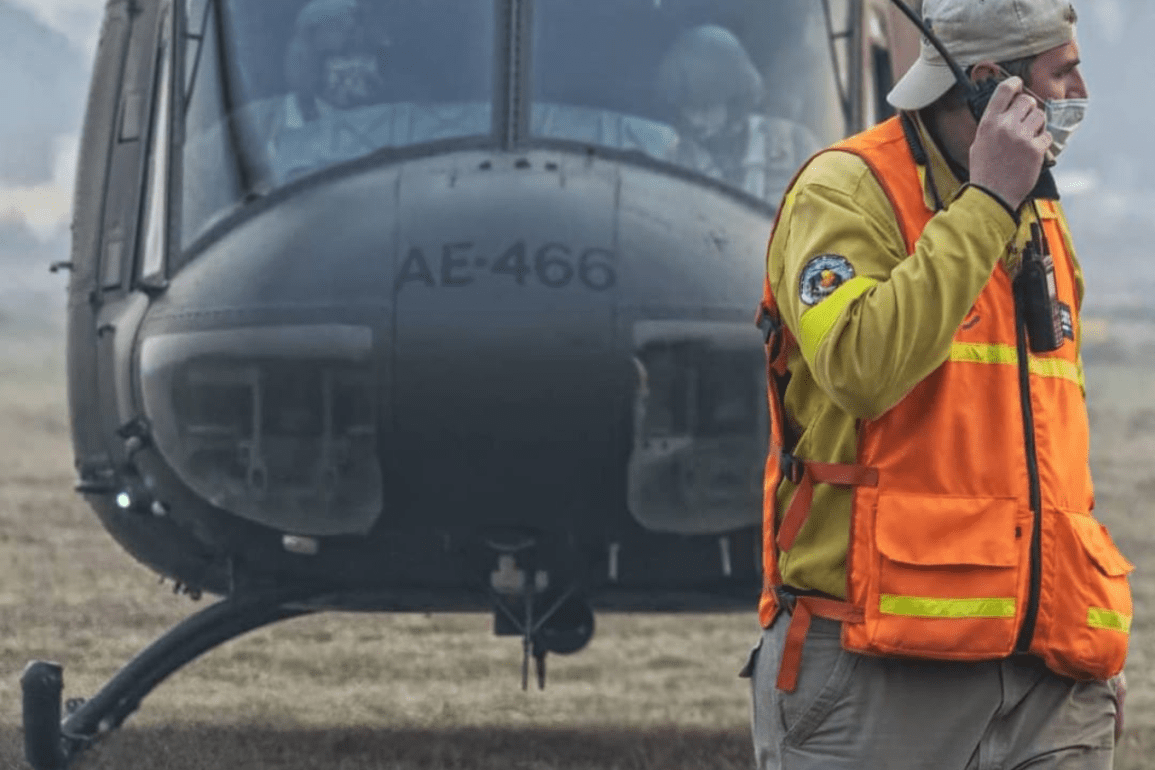

EL ESTOR, Guatemala — For nearly seven years, I endured judicial harassment and threats for exposing companies causing pollution in my town. As an environmental journalist in Guatemala, such challenges remain common, but I never anticipated the full consequences of my persecution.

It was not until January of this year that I began to feel free to walk the streets again. These experiences leave deep scars and have strained my relationships, leading to estrangement from part of my family.

Read more environment stories at Orato world Media.

Exposing police violence: “My legs went weak; I knew I was in trouble”

In May 2017, while working as a freelance journalist and for the environmental management office in the town of El Estor in Guatemala, a group of fishermen came to me at work and at home. They urged me to visit the nearby lake. I saw the concern on their faces, but never foreshadowed what awaited me.

When I arrived at the site, I felt stunned. A large stain crossed the lake, turning it red. I began taking photos and documenting the scene, trying to comprehend what happened. “We’ve never seen anything like it,” some of the elders told me. Their words touched my heart and underscored the seriousness of the situation. I felt compelled to investigate, thinking, “If I don’t do it, who will?” I committed to the process, unaware of the severe consequences ahead.

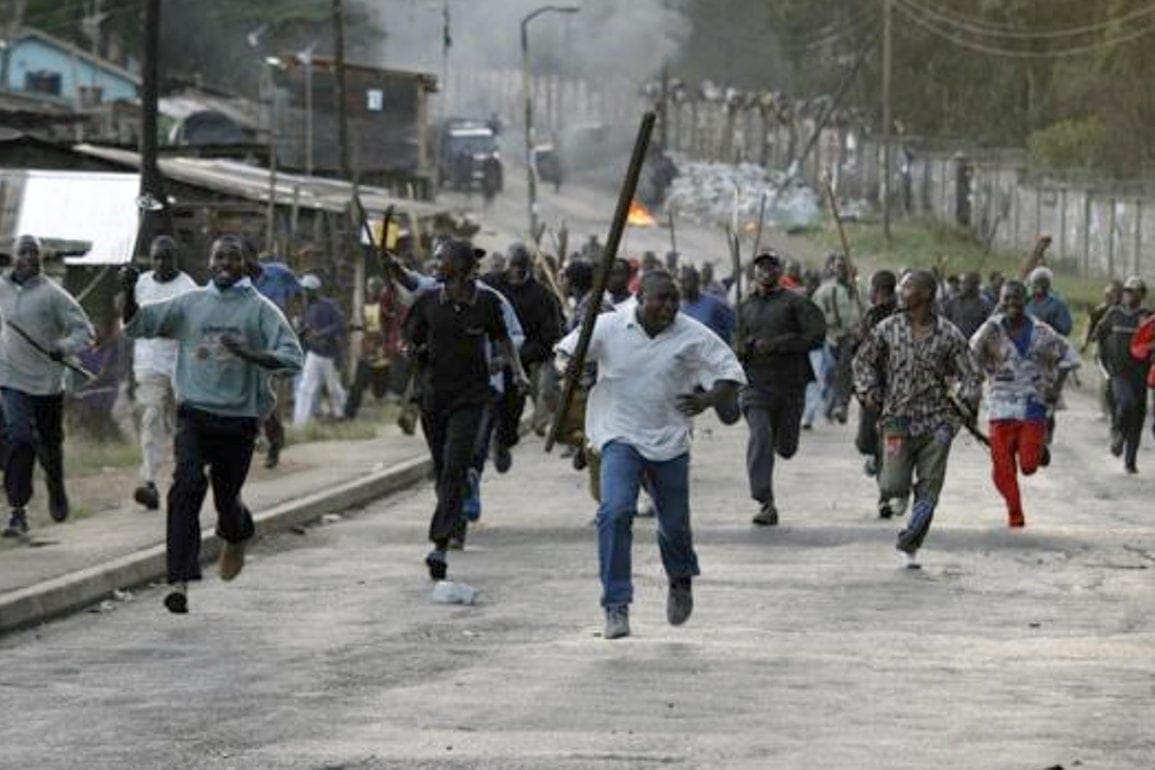

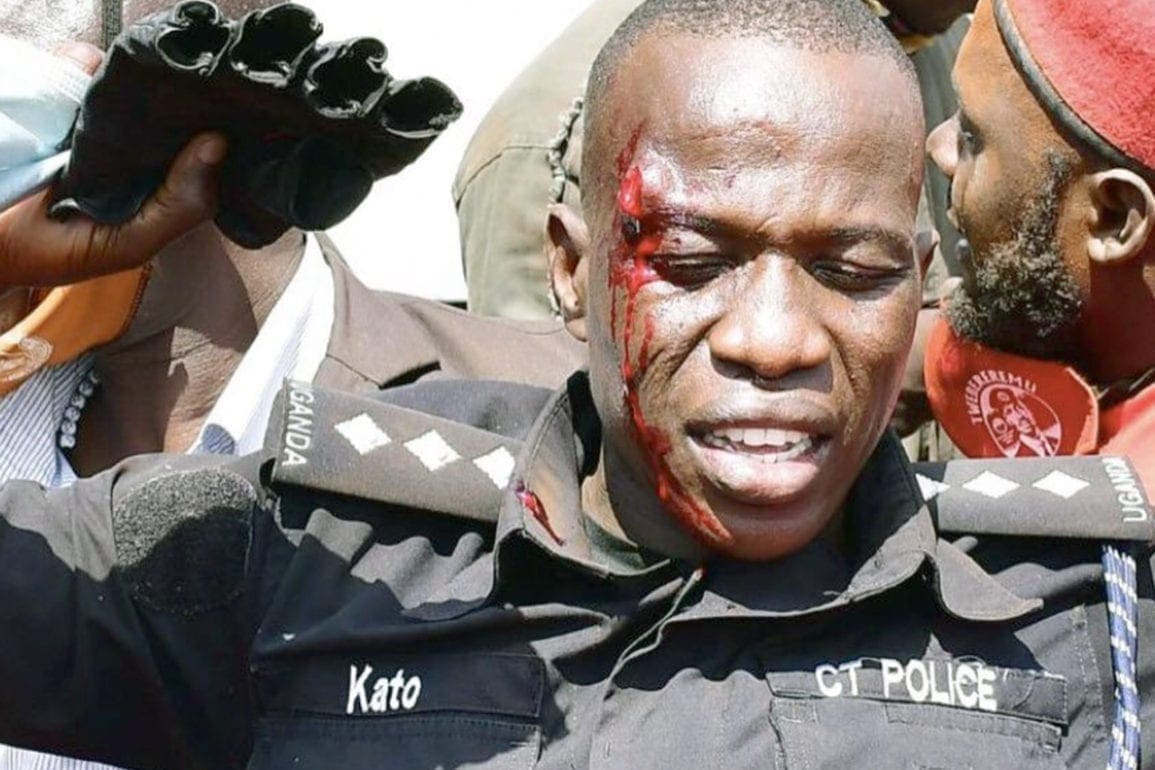

A few days later, I covered a protest against the polluting company. During the demonstration, fisherman Carlos Maaz was murdered. I captured photos and videos, not realizing who shot him. While the police denied any injuries or fatalities, I gave interviews confirming what I witnessed with my own eyes.

That night, I arrived home and reviewed the photographs. I saw that the shot which killed the fisherman appeared to come from the police. I had irrefutable evidence. My legs went weak; I knew I was in trouble. Then the phone rang, and I listened to the first of the threats. That same night, I received several calls. The last one warned, “We know where you live, we know your neighbors, and we’re coming for you.” Part of me hoped it was a joke, so I kept quiet.

Warrant for my arrest: facing familial, community, and social disintegration

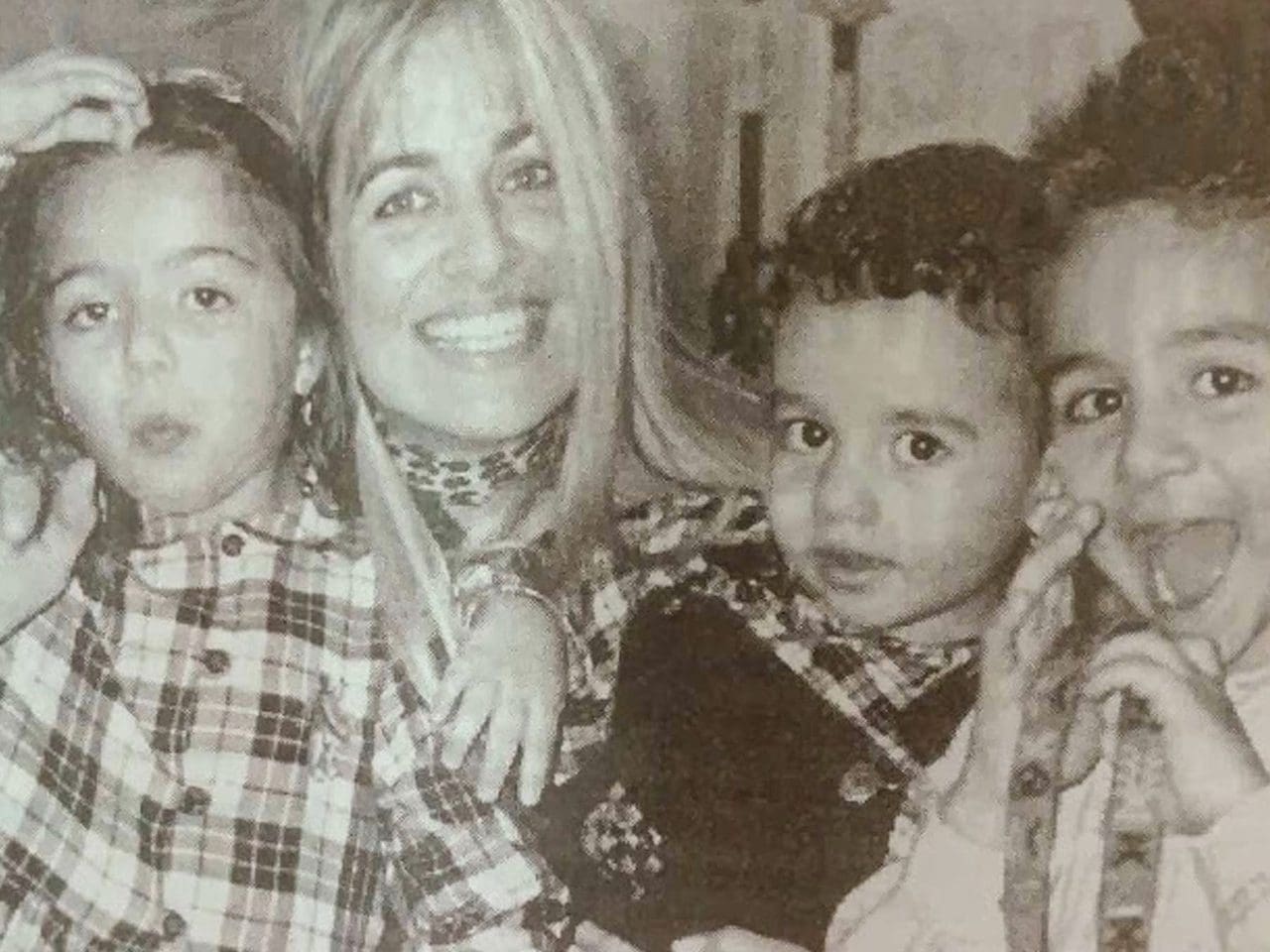

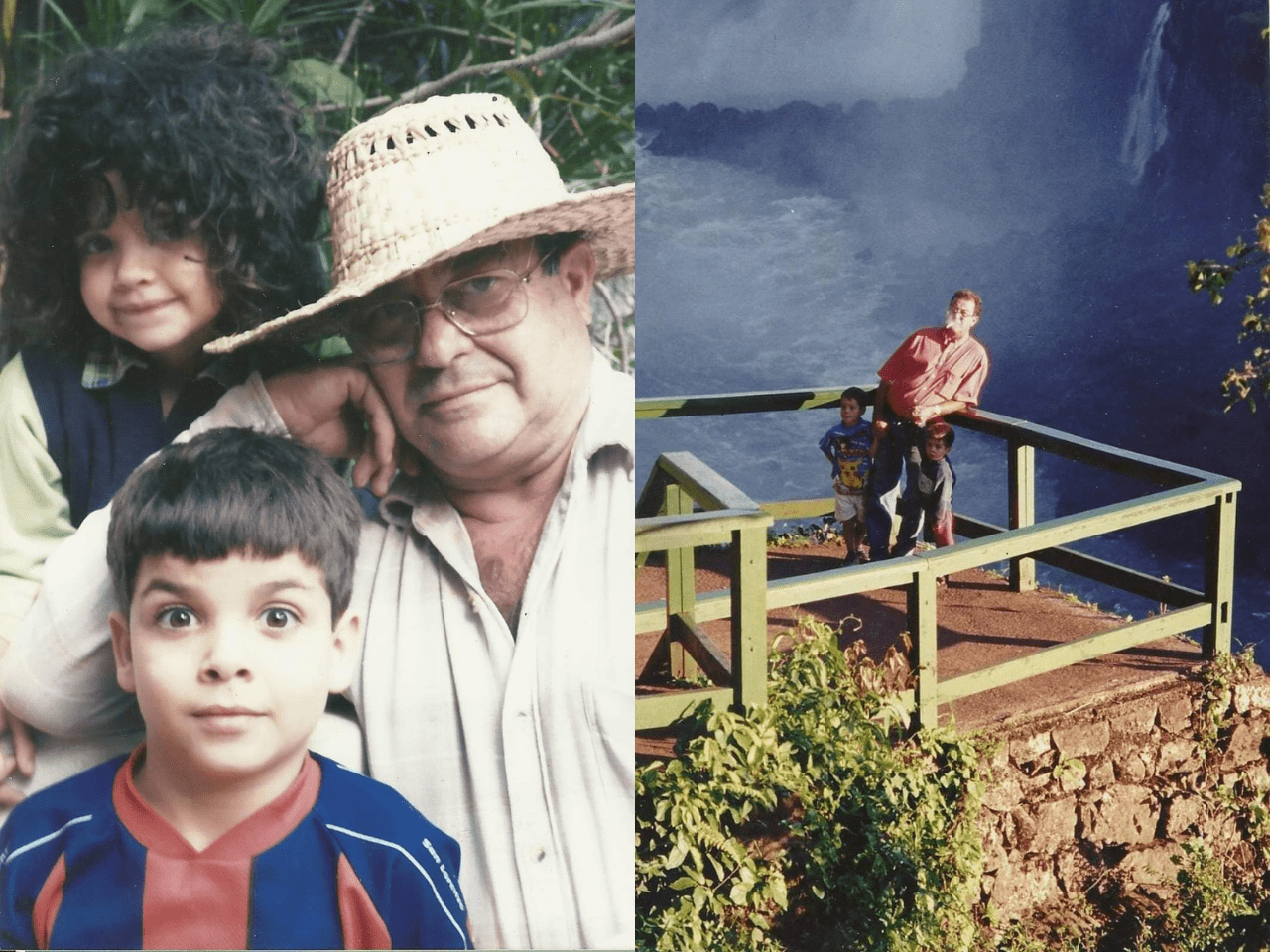

Three days later, I saw armed individuals near my house. I lived with my son and daughter, then eight and nine years old. At the same time, the fishermen called to tell me the authorities issued a warrant for my arrest. I looked at my children and, without giving them too much information, told them we needed to leave immediately.

They looked at me with fear but also trusted me. For a while, I left them with my sister, and I left town. “Take good care of yourselves, I’ll be back soon,” I told them, fighting tears. My lawyers requested a hearing, but it took a year and a half to materialize. Though I did not face prison, I remained under house arrest and had to report monthly to the Public Prosecutor’s Office to prove I had not absconded.

I faced the disintegration of family, community, and my social connections. The company hired my children’s mother and her partner to work in the mine and she sued me for custody, claiming I was a criminal. They also hired some of my uncles and brothers, leaving me isolated. Only one sister knew my whereabouts and helped me see my children.

They launched a defamation campaign against me, turning many people hostile. I had to leave my community. Though I continued my work, I felt like a ghost, living in fear and isolation. Venturing outside, I noticed possible police drones tracking me, which only fueled my determination to investigate further.

I felt like a prisoner but also recognized the power of my role as a journalist. I needed to tell the stories of contamination, murder, and persecution happening in my region. Some colleagues doubted me, seeing me as an activist rather than a journalist. Online harassment and accusations often plunged me into despair.

Enduring threats:”I found myself under surveillance by those co-opted by the mine”

Sitting in my chair, staring at the wall, I often wondered, “Why did I get into this?” Yet, an inner strength surged within me, urging me to continue. I deeply identify with my Mayan heritage. In Mayan philosophy, we are never alone. The energies and wisdom of our ancestors, the grandmothers and grandfathers, are always with us, along with a guardian spirit, the Nahuatl. Suddenly, I began to feel those energies, reassuring me I was not alone and remained on the right path.

However, I started smoking again. I previously managed to quit but began using cigarettes again to calm my nerves and alleviate stress. I spent long hours reading poetry, escaping my seclusion and problems, letting my thoughts take flight. In 2019, I returned to El Estor, hoping to carry on, but I found myself under surveillance by those co-opted by the mine.

One night, strangers entered my home and threatened me. I remained calm as they took my camera, cell phones, flash drives, and even a broken tripod. Thankfully, my computer remained with a friend. I had to leave again, devastated. On January 31, 2024, fellow journalists in Europe demanded action on my case.

Several members of the European Parliament spoke out in my favor, and I finally obtained an audience with the mine’s lawyer. Initially, she sent a document indicating her withdrawal from the case, but the judge did not validate it because she wasn’t present. It felt tense as my lawyers negotiated her attendance. After agreeing to no photos or videos, she arrived, and the nightmare finally ended.

After seven years, persecuted journalist is finally free

I felt ecstatic when the persecution against me came to a conclusion, and I barely believed it. After so many years, I was finally free. The judge dropped all charges against me. It felt hard to comprehend I could now live without reporting to the Public Prosecutor’s Office every month. For seven years, I could not have a beer with friends, legally prohibited from such activities.

Being able to return to life felt like being reborn. I could laugh with those close to me once more—I was truly living. Despite my freedom, the psychological after-effects linger. When I ride my bike, I often tense up, fearing the police or others might be following me.

I also deeply miss my daughter, who chose to live with her mother amidst this turmoil. Returning to who I was before remains difficult. I see it as a process. Due to the political crisis in my country, I relocated to Europe. Journalists covering environmental damage and human rights violations in Guatemala becomes targeted as enemies of the Public Prosecutor’s Office. Press freedom becomes increasingly restricted in such an environment. For security reasons, I left my country for a few months. Yet, I hope to experience many more sunsets and achieve goals and investigations that remain dear to my heart.