Me hice mundialmente famoso pintando al legendario futbolista Diego Maradona

Cuando veo una pared enorme, me dan muchas ganas de pintarla. Tantas que superan el miedo que genera colgarse tan alto para hacerlo. Cuando estoy arriba, me pongo música relajante para calmarme, y pienso en las medidas de seguridad, en los arneses y sogas que me sostienen. Después, me concentro en pintar.

- 3 años ago

enero 5, 2023

CANNING, Argentina — Many believe Diego Maradona is the best soccer player who ever lived. He died in 2020 at 60 years old, and I painted a massive mural in his honor in Canning, Argentina.

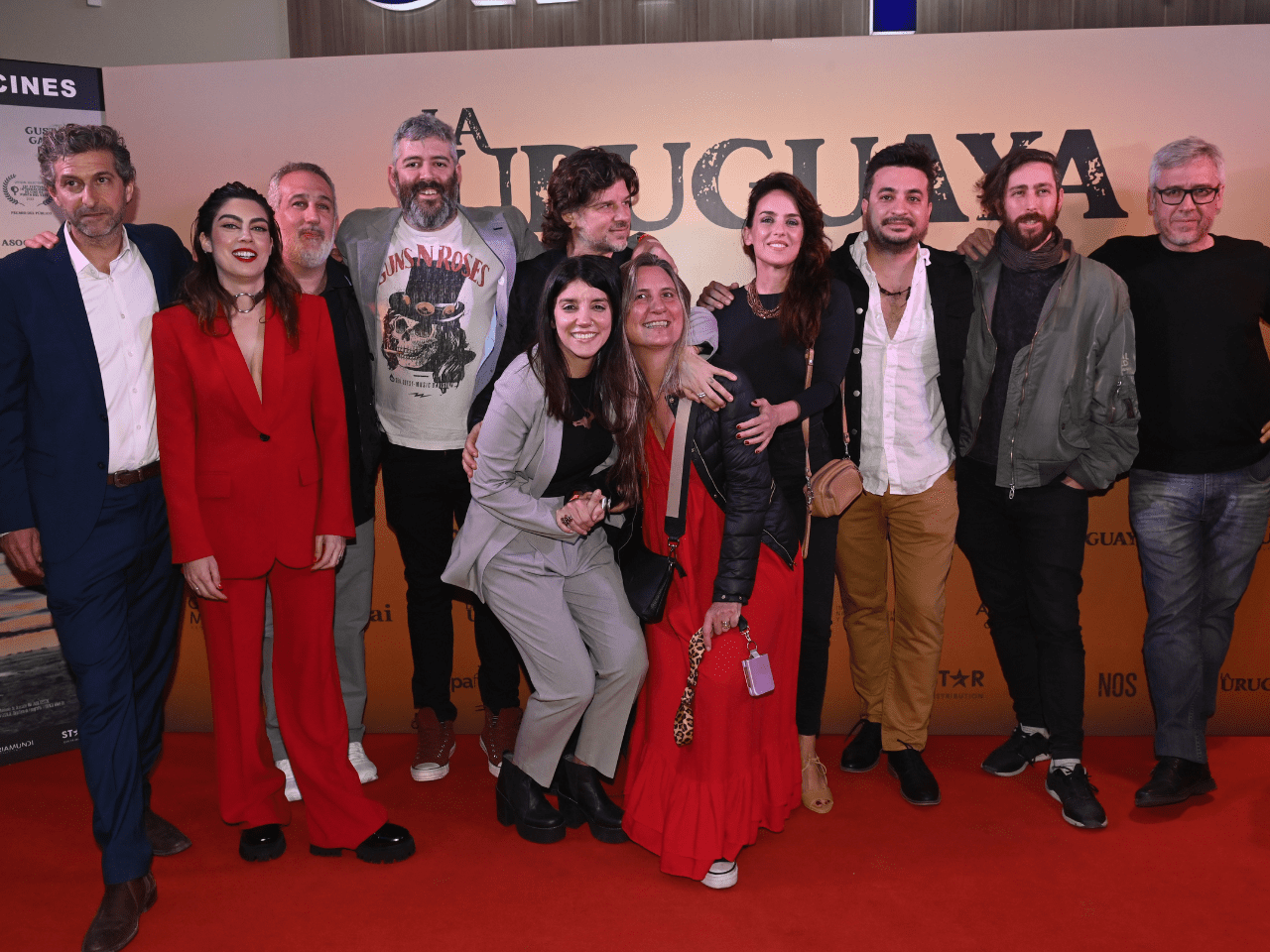

The artwork spans 131 feet high and 39 feet wide. On the day of its inauguration, a hymn played gently in the background. Maradona’s wife Claudia Villafañe, and his daughter Giannina, showed their emotions as they looked at him up in the sky, so close to heaven.

That day, it felt like Diego was with us. As the crowds and the buildings surrounded me, I thought to myself, «I am here. I made this image – this artwork his loved ones came to see.» Emotions overwhelmed me.

Hanging from a tall building as bees buzz about

When I see a huge wall, I want to paint it. In fact, the urge to paint helps me overcome the fear of hanging so high to do it. When I’m up there, I put on some relaxing music to calm my nerves. I think about the safety measures, the harnesses, and the ropes that hold me up. Then, I focus on painting.

Read more stories from Argentina at Orato World Media.

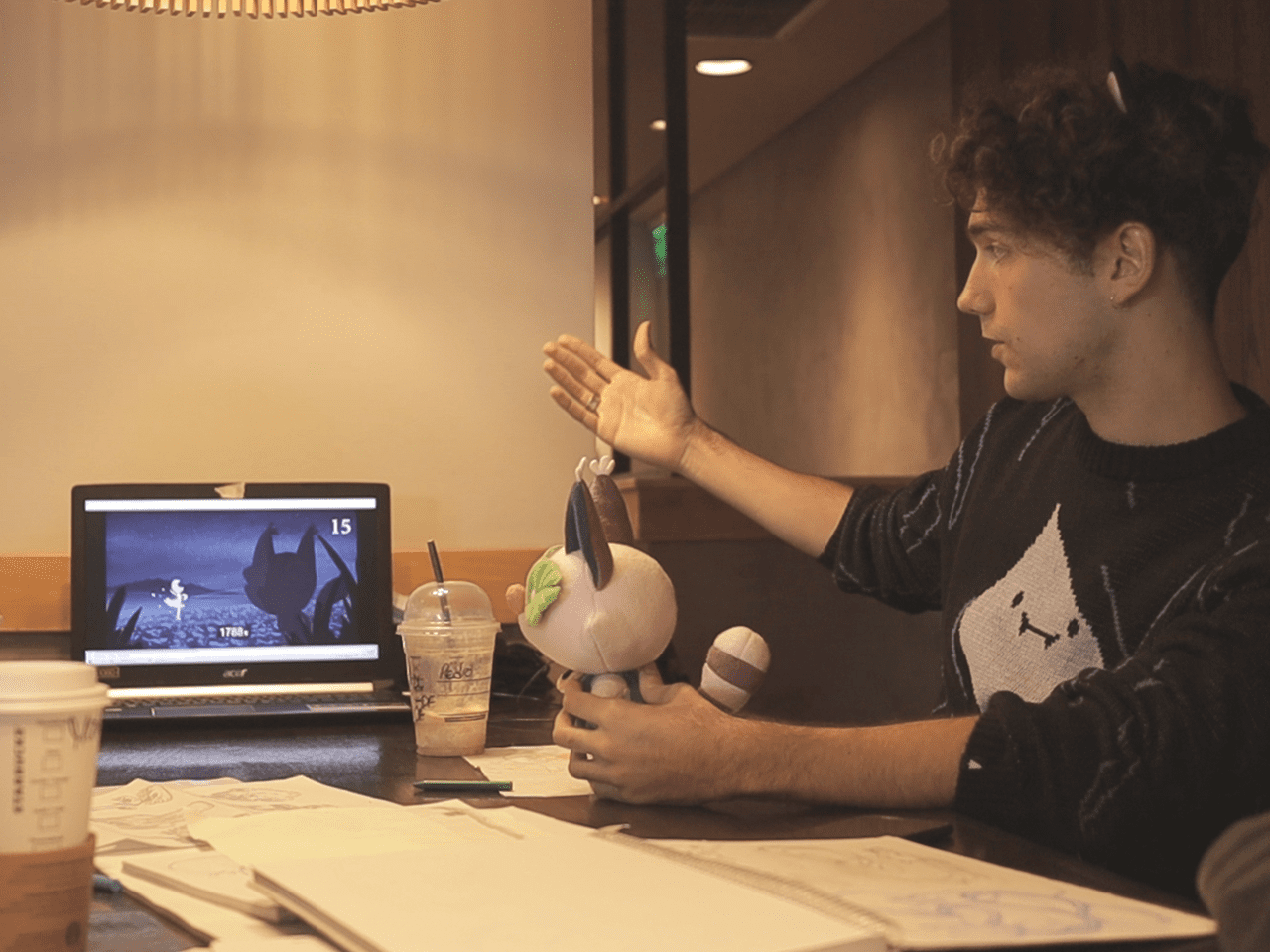

I painted the Maradona mural in Canning with my assistant, Nico. We started on a very windy day. The rockers’ arms moved heavily, and the ladder kept falling off. On top of it all, bees swarmed around us. I played music by the group Above & Beyond to relax.

I always start a job by sketching on the wall – a task that helps me think about proportions. On that first day, after scribbling different shapes, the image of Diego came to life. Getting down and seeing it there, in giant proportions, motivated me and Nico to continue.

The first time I painted Diego was on the day he died. On seeing the news, I went through different television channels to confirm it was true. My first thought was, «Now I’m not going to be able to meet him anymore,» which is something I always dreamed of. In Argentina, most of us believed Diego would be around forever.

One drawing leads to an art career painting Maradona

On November 25, 2020, saddened by Maradona’s death, I went into my workshop to do what I do best: communicate through art. That day, I painted a close-up image of Diego in black and white. It showed him holding his gaze, a half-smile on his face.

I added an effect that made it seem as if he were vanishing into a light blue and white background. After uploading the image to my social media accounts, notifications and comments flooded in.

From that moment forward, I began to paint the iconic player often. A television show summoned me to paint Maradona, and the president of Argentinos Juniors asked me to paint my first Maradona mural in the club where he played. With the mural in place, it became like a sanctuary.

I created an exhibition with drawings of Diego at different stages of his life. I painted him fat, skinny, blonde-haired, young, playing soccer, and even wearing a fur coat with a glass of champagne in his hand. People started asking me to paint him, and I never stopped. Any Maradona fan know my work. His entire family took me in. I think if Diego could see these works today, he would like them.

The immensity of murals must be seen in person

I cannot blame myself for failing to show my work to Maradona while he lived. At that time, I was developing my style and had not started painting murals yet. While I believe things happen for a reason, I also urge people to do what they dream of. Do not wait. Tomorrow is not always guaranteed.

While I never met Maradona, through painting, I have gotten to know him deeply. Anytime I meet someone who knew him, I ask questions. What was he like? How did it feel to be close to him? I can then insert their experiences and feelings into the images I create.

Seeing murals in photos does not compare to seeing them in real life. When you look upon my mural of Maradona in Canning, you feel his immensity. You raise your head to see him, and he is there, in the sky. I watch people visit and cry when they look at him.

The experience is not exclusive to Argentina. In Italy, I painted a mural of Maradona and the people reacted so strongly that the mayor changed the name of the street to Vía Diego Armando Maradona. In Russia, we transformed a whole town named Solnechnodol’sk into art.

I worked alongside other artists, and we painted murals all over. Today, it serves as a tourist destination. The same thing happened in Wynwood, Miami, where we added color to the entire region with murals. Nobody went there before, but today, it remains a central tourist location. Art attracts people.

Murals become a social venture where we engage the public

When I started doing art, I began with illustrations then cartoons. Later, I began painting pictures and giving classes. I taught tattoo artists and muralists. They began organizing outings to paint, and I enjoyed the discovery process. Today, I have painted murals around the world. My distinct painting technique stands out. I apply the paint to the walls with realistic detail.

Murals change culture. When you paint one in front of a bar, the bar becomes known for its murals. Our art becomes part of people’s biographies. After painting a tunnel in homage to Argentinian comedian and producer Jorge Guinzburg, my work appeared on his Wikipedia page. I find it amusing.

Paintings generally stay in someone’s home, but murals leave something for all people. This is what attracts me to the medium. It gives color to the streets. When muralists come together we share in a social venture as a team, performing in the open air. We share moments with people nearby, rather than being confined to a studio.

While you have to watch the weather and take extra precautions, you also witness people’s reactions and engage with the public.