People with albinism denied medical care

COVID-19 hampering access to medical care for people with albinism in East Africa

- 5 years ago

December 22, 2020

NAIROBI, Kenya — As I enjoy the view of the sun setting from my tiny balcony, memories from March strike me again.

The month that Kenya reported it’s first COVID-19 case was also the month I was denied medical attention due to my skin condition.

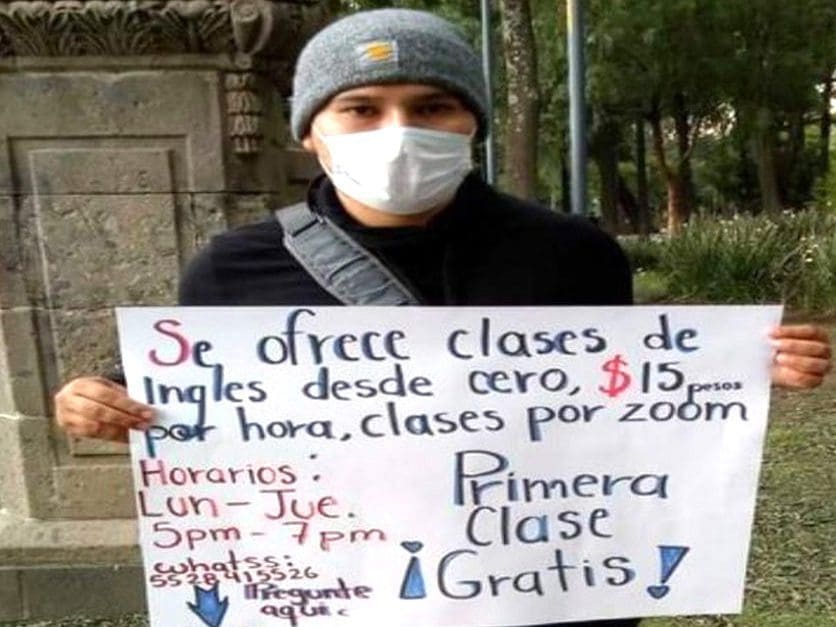

A few days after the first case, I felt unwell and went for a medical check-up. Upon arriving at the facility on the outskirts of the central business district in Nairobi, I went straight to the waiting bay. It wasn’t long before everyone stared at me.

The clock kept ticking and the line moving until it was my turn to see the doctor. I entered the room, and before I could say hello, the young nurse left.

I waited for her in that room, but she was gone. Suddenly, I was told to leave the office and not return until COVID-19 was contained.

Shock and surprise gripped me.

“Why?” I asked

Their answer was simple: They believed I was a carrier of COVID-19 due to my skin pigmentation. I tried to explain my skin condition, but all was in vain. They had already made their decision not to attend to someone with albinism.

RELATED: Zimbabwe albino community faces rituals, oppression

RELATED: Maasai women ‘break tradition’ to flatten COVID curve

I was so heartbroken and shattered as I left the hospital. In my mind, I questioned myself many times why I had to be born with this condition. In a country where universal healthcare is one of four main agendas, I could not imagine why someone’s skin pigmentation is a barrier to accessing medical care.

My experience reopened the scars in my heart — scars born from a life of fear and prejudice.

It’s been more than nine months since I was denied medical access. Since then, reports have emerged highlighting the medical neglect of people with albinism.

A life with albinism

My story is one of agony that few will understand.

I have suffered at the hands of those who sought to kill me and use my body for rituals. I have escaped multiple life-threatening situations aimed at ending my life. These terrible fights chronicle my drive to be who I am today.

As a kid on the border of Tanzania and Kenya — a region where people living with albinism are often killed — I taught myself to survive.

I was raised by a single mother who recently told me my father abandoned us due to my condition. He blamed her for giving birth to a child with albinism. I have seen my mother do unimaginable things just to protect me.

After escaping several attempted kidnaps, my mother decided we should leave the area and start a new life in Nairobi. Life was totally different in the city. I even started school despite my advanced age. Even though I still faced discrimination, it wasn’t the same as what I experienced back in my village.

But the discrimination continued, so I took things into my own hands.

I enlisted witchdoctors to protect my life. My mother, believing that witchcraft is wrong, was unaware of these efforts. She would never condone my plans. Though I realized what I did was wrong, it helped me protect my life and that of my mother. Many who oppressed me found their lives turned upside down.

Deep down, I knew it couldn’t continue. Ruining the lives of others made me no better than those who oppressed me. I decided to stop and instead focus on the positive in my life. I never wanted to hurt other innocent people.

Harsh reality in Africa

Being white in a black population is considered a curse with elements of fear, ridicule, negativity, and social exclusion.

Though we have made positive steps in championing our rights, the COVID-19 pandemic is slowly reverting our progress to the days when we lived in fear.

People with albinism face bullying at school and more extreme manifestations such as kidnappings, grave desecrations, and physical attacks that are often fatal and lead to dismembered bodies. These acts have been promulgated by myths and superstitions purporting that our body parts hold magical powers.

Women and children are particularly vulnerable as myths claim that sex with a woman with albinism can cure HIV/AIDS. These claims make us targets of sexual assault. Others claim that children’s body parts yield more potent potions.

Mothers are ostracised if their child is albinistic. It’s seen as the result of a curse, a bad omen, or infidelity. Albinism is no more a choice than it is the result of a curse. All we can do is request acceptance in society.

Kenya is taking steps forward in protecting and supporting people with albinism. But it isn’t enough. We need justice for victims of attacks and socio-economic support for victims and their families.