Over 1,300 people died in Saudi Arabia’s Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca: eye witness recounts events

On my first day at the camp, an elderly woman and I spent two hours walking back to the site after completing our rituals. With limited transportation and overpriced taxis, we found ourselves walking everywhere. The absence of nearby shopping facilities only compounded our difficulties, and the heat magnified the problem.

- 2 years ago

July 15, 2024

MECCA, Saudi Arabia ꟷ I attended my first Hajj pilgrimage to the Holy City of Mecca in Saudi Arabia in June 2024, where more than 1,300 people died. I saved my money and instead of buying a car as planned, I applied for a lottery to attend Hajj through a tourism company. [Several years ago], Saudi Arabian officials announced women under 45 could apply for Hajj, so at 38, I decided to attend.

While the price offered by the Ministry of Tourism in Egypt remained significantly higher than previous years due to the devaluation of local currency, I felt fortunate my name appeared in the lottery. I selected the most economical package, including three days in five-star hotels followed by rented accommodations. In the hotels overlooking Haram, I felt good about the situation, but everything changed when we moved into residential buildings and camps.

Suddenly, I found myself with 135 women, crammed into one building

On my first day at the residential building in Mecca’s Al Zaher area, an elderly woman and I spent two hours walking back to the site after completing our rituals. With limited transportation and overpriced taxis, we found ourselves walking everywhere. The absence of nearby shopping facilities only compounded our difficulties, and the heat magnified the problem.

We shared one tiny refrigerator and meals consisted of rice and protein. They offered no vegetables or alternative options. Food availability and delivery became monotonous and irregular, and the bathroom conditions deteriorated with overcrowding. The building resembled female student housing, with five beds crammed into one room. The extremely cramped space lacked even a table on which to place our belongings.

Next, the Egyptian Tourism Company I patronized rented a building in Mina, east of Mecca, far from the ritual sites. The space quickly became overcrowded. One hundred and thirty-five of us shared the accommodation. A Saudi Mutawaf, [an individual appointed by the Ministry of Hajj to act as a guide for pilgrims], claimed the services provided met the standards requested by Egyptian tourism companies.

In the buildings, each Egyptian pilgrim had less than one meter of sleeping space, while Kuwaiti pilgrims had one and a half meters. The tourism company responded that it didn’t expect this deteriorating level of service. At times, I could only use the facility once a day. The infrastructure fell apart and medical facilities failed to handle the crowds. People began showing signs of dehydration and heat exhaustion. We had nowhere to turn for help.

I watched as a woman at Hajj slipped into a diabetic coma

On Arafah, [the second day of the Hajj pilgrimage], the people who paid for the low-cost Hajj like me stood in Arafat amid severe overcrowding as temperatures soared. One of the pilgrims we knew got lost in Arafat. An elderly man, we grew worried, but found no one to help us search. We turned to social media until we located him.

Meanwhile, we saw people sitting under trees in Mina and Arafat. With no proper crowd management, things began spiraling out of hand. I couldn’t tell if the people underneath the trees were alive or dead. Yet, more difficulty would arise when my neighbor, a 50-year-old diabetic woman, collapsed in Mina. I frantically sought help from the tour guide, pleading with him to contact Saudi employees at the camp, to no avail.

The camp lacked basic medical equipment like glucose meters, blood pressure monitors, or oxygen supplies. With no sign of a medical convoy, I desperately searched for a doctor in the nearby men’s camp. When the doctor arrived, he attempted first aid but turned to me with devastating news.

“She is in God’s hands. She has passed away,” he said. I fell to my knees, uncertain what to do next. I felt completely helpless. Not a single ambulance was available to transport the woman’s body, and we waited hours before they moved her.

It seemed as if human life held no value. Each person was left to their fate. Many people died like this woman, with most of the deceased being elderly. It appeared to me that only young people could endure the severe conditions.

Faith dictates Muslims must make the pilgrimage to Mecca once in their lifetime

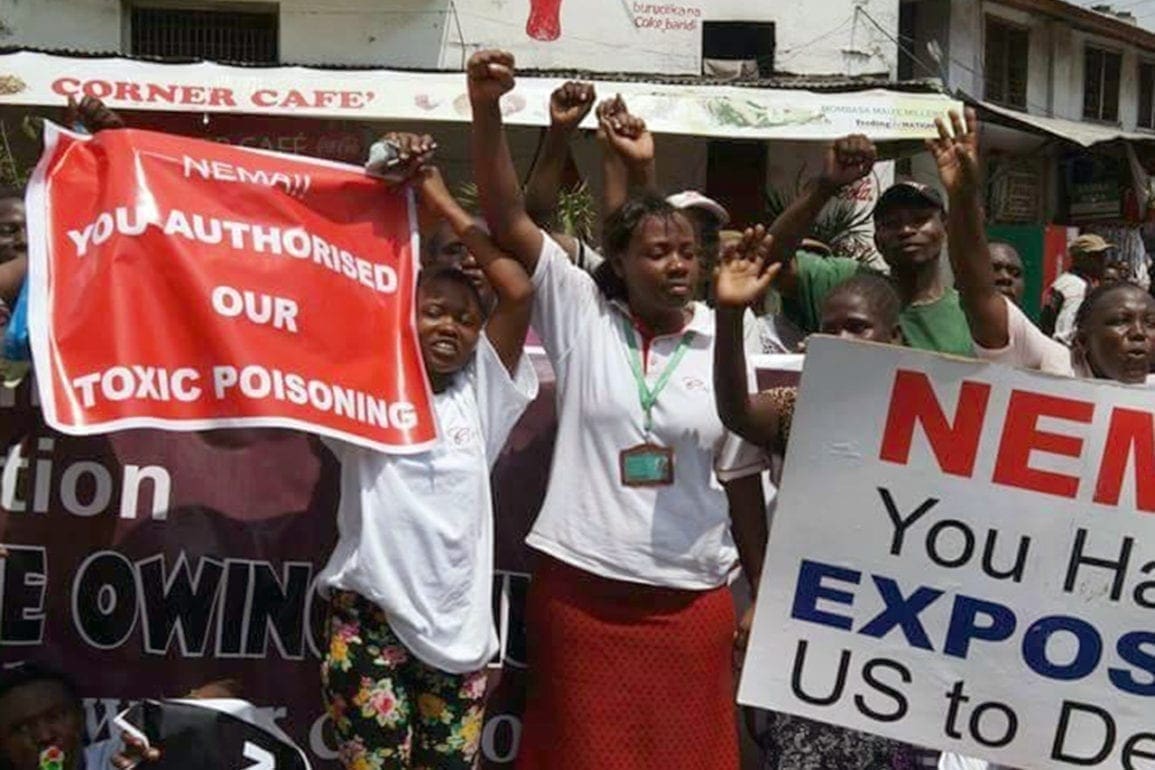

As I reflect on the aftermath of the tragedy at Hajj in Saudi Arabia that took over 1,300 lives, it appears to be a case of trading accusations. One of my fellow pilgrims there told me the Saudi Arabian Mutawaf who accompanied us indicated the accommodations met the requirements of the Egyptian tourist companies. The tourist companies claimed they did not expect the situation to deteriorate as it did.

[According to news reports, Saudi Health Minister Fahd bin Abdurrahman Al-Jalajel said that 83 percent of the deaths were unauthorized pilgrims who had walked long distances in the heat.” Soon after, “Egyptian Prime Minister Mostafa Madbouly stripped 16 tourism companies of their licenses and referred their managers to prosecutors for enabling illegal pilgrimages to Mecca.”]

I suggest that failure to provide camps for pilgrims performing unofficial, unplanned, or unauthorized Hajj became a major contributing factor. The Saudi authorities also exacerbated the crisis by granting visit visas during Hajj season when they should have refrained from doing so. Most of these people traveled two weeks before Hajj.

I hope in the future, decision makers allow people to attend Hajj based on health rather than financial means. [This is important because one of the five pillars of Islam central to Muslim belief is that every Muslim must make the pilgrimage to Mecca once in their lifetime.]

Place people in good health in remote places and offer comfort to the elderly, those with health problems, and families with children. There should be no caste distinction while performing God’s rituals. Not just Egyptians, but many nationalities suffered in this situation.