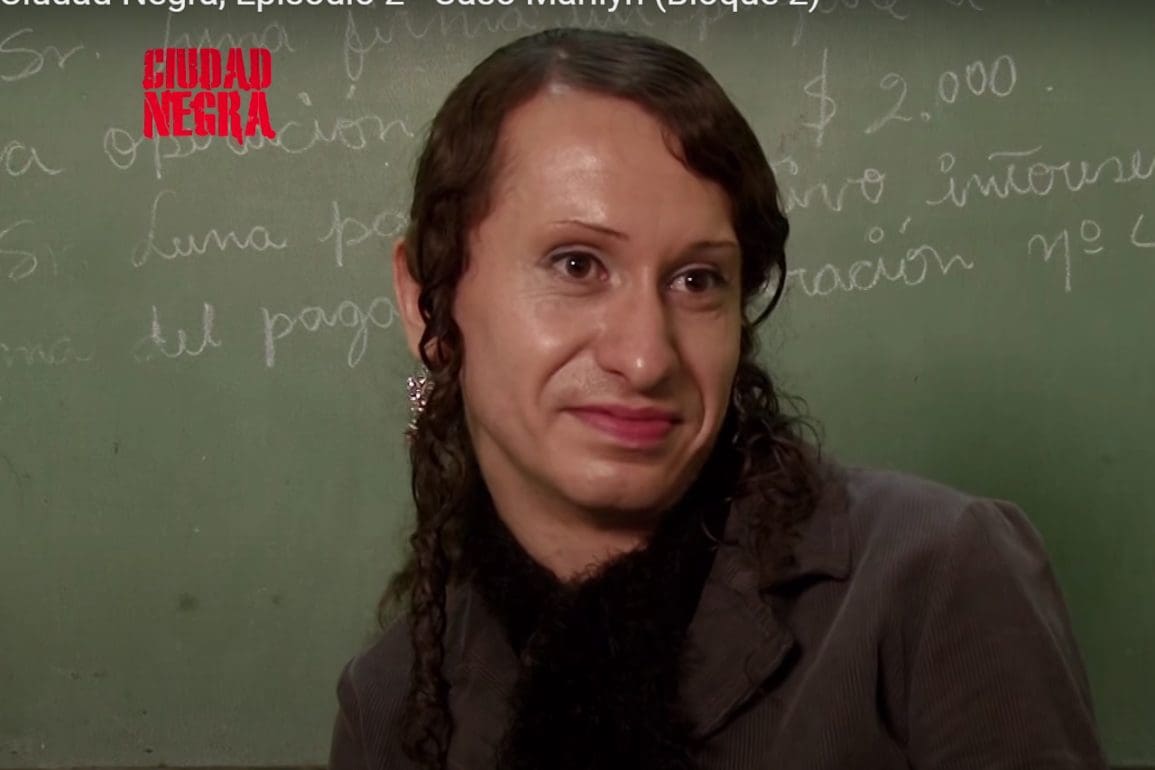

Wrongfully imprisoned mother becomes activist, denounces injustice in Mexico’s federal women’s prison

The authorities stripped us completely naked in front of federal police, forced us to do squats until we collapsed from exhaustion, and beat our bodies… Even then, I was one of the lucky ones. Others endured electrocution, their piercing screams echoing through the space.

- 1 year ago

August 22, 2024

TEPIC, Mexico — Prison marked the darkest period of my life. Women’s prisons in Mexico intend not to rehabilitate; they exist to break you, and they succeed. They locked me away for 24 hours a day, leaving me with nothing but a small, high window I could barely reach. It offered just enough to feel a sliver of air, which became my only connection to a world that seemed impossibly far away.

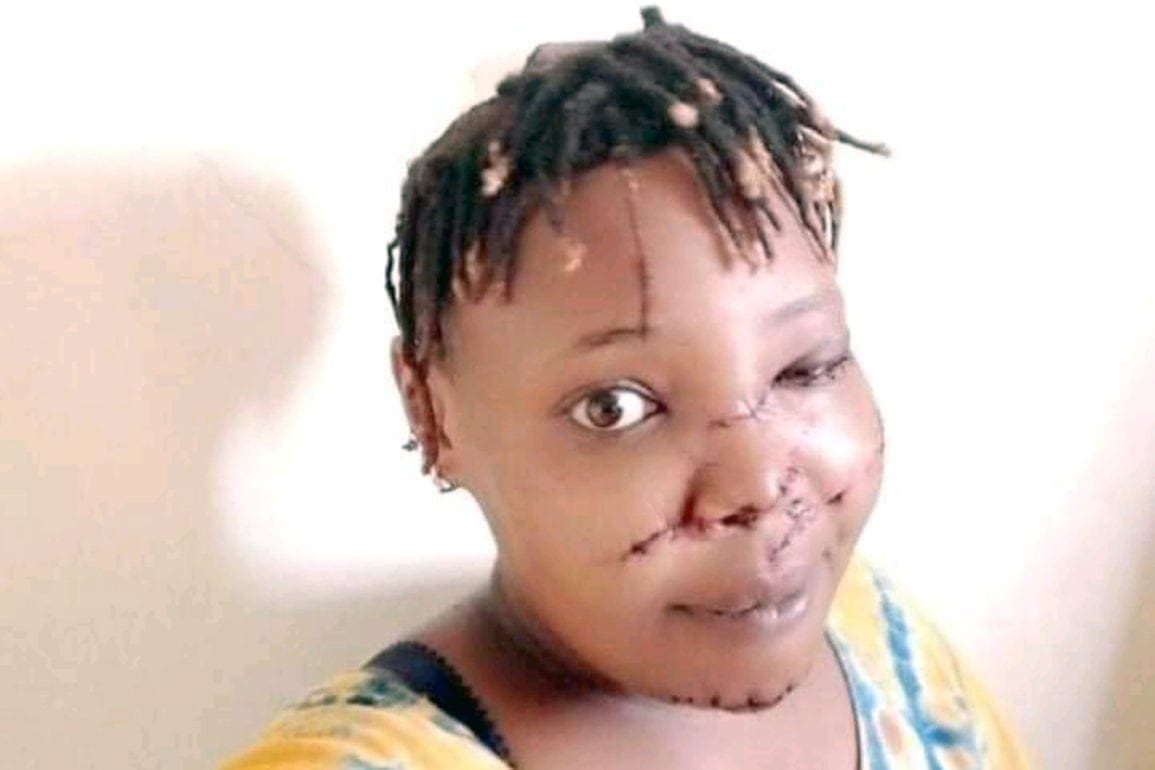

The desperation inside those walls ate away at me. The constant thought of ending it all became overwhelming and I felt a desperate urge to smash myself against the bars. The only thing keeping death at bay was the support of my fellow inmates, who held me back and calmed me down. Others ended their own lives. Now, on the outside, I carry the scars, and I fight for prisoners’ rights for those still trapped behind those walls, while I try to rebuild my own life.

Read more Crime & Corruption stories at Orato World Media.

The night everything changed: terror at my doorstep

In 2014, I lived with a man much older than me, whom I shared children with. Around 1:00 a.m. on August 22, I heard a loud and relentless banging sound on the front door. I froze at first, then checked the cameras. A group of hooded men stood outside, demanding I open the door. They never identified themselves as police, and my heart raced with fear. “Is this a kidnapping attempt,” I wondered.

I rushed to my children’s father’s room, shaking him desperately to wake him from his drunken stupor and give me the keys. He never budged and panic set in. The banging at the door grew louder, reverberating through the house like thunder. Instinctively, I locked myself in my room, shielding my children the best as I could.

From outside, these men shouted insults at me, demanding I let them in. I felt cornered and trapped in my own home. With no other option, I let them in. They stormed the room with their hoods pulled tightly over their faces, their eyes filled with hatred. “Where is he?” they demanded. They asked about someone by a name I didn’t even know. Then, a blow landed on my head, sending me sprawling to the side of the bed.

My vision blurred, but I still saw my children’s faces, wide-eyed with terror. I turned my head and saw the guns pointed at me, unable to understand what was happening. The men – who were officers – took me away to the police station and there, they accused me of crimes. I had no idea the father of my children had a record of trafficking undocumented immigrants.

A window to nowhere: surviving the isolation of Cefereso No. 4

The courts sent me to Cefereso No. 4 in Tepic. It felt as if hell swallowed me whole. They locked me up under a strict regime 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Completely cut off from the outside world, I had no idea where my children were. Breastfeeding at the time of my arrest, in prison the milk leaked out of me, and I cried thinking of my children. The closest I came to freedom was to stretch my hand toward the small window high up in my cell and let the air brush against my skin.

The guards ruled over us through fear with two, in particular, I dreaded the most. Every time they came near, my body trembled uncontrollably. They forced us to stand with our hands behind our backs, heads pressed against the wall, and eyes on the floor. In those moments, I silently prayed for the prison search to end quickly.

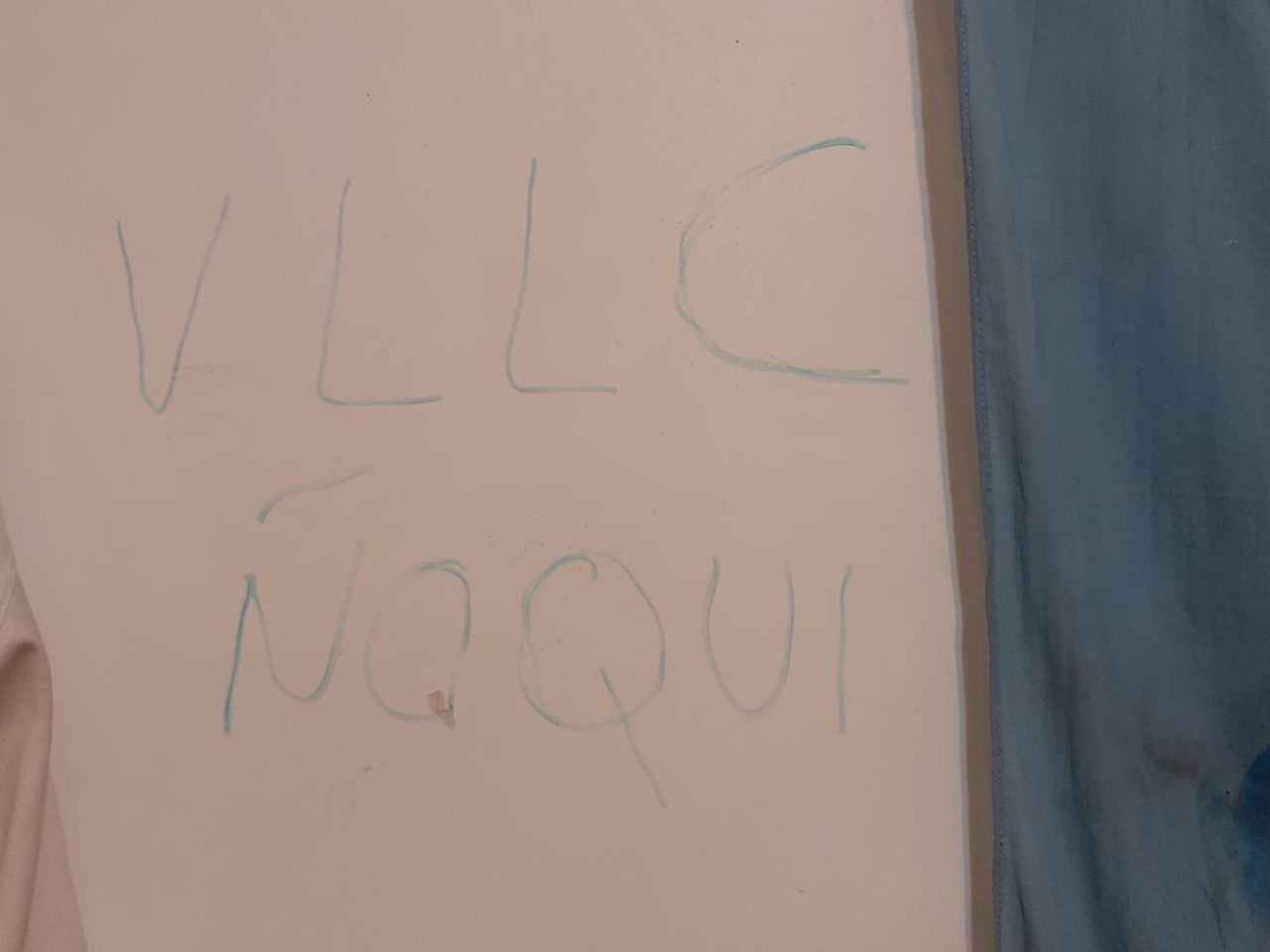

They tore through our few belongings, sweeping them into the black bags they carried. Every month, they took away the two or three sheets of paper and the pen they gave us. By taking the pen and paper away, they stripped us of our only means of communicating with our families, like messages tossed into the sea of uncertainty. We never knew if our words reached them, and no responses ever came.

When the paper ran out, they forbid us from borrowing from others. Breaking that rule meant severe punishment. For nearly two years, I lived cut off from any word of my children. Every day, I thought of ending my life. The despair in prison felt suffocating, like falling into a bottomless pit. You become so desperate, so trapped, life loses all meaning.

Transferred to hell: my harrowing experience from to Cefereso 16 prison

In moments of desperation, I clung to the bars, banging my head against them. My fellow inmates rushed over to calm me and gently remind me, “One day, the nightmare will end.” The officers, on the other hand, could care less if we hurt ourselves or died. Eventually, though, you adjust.

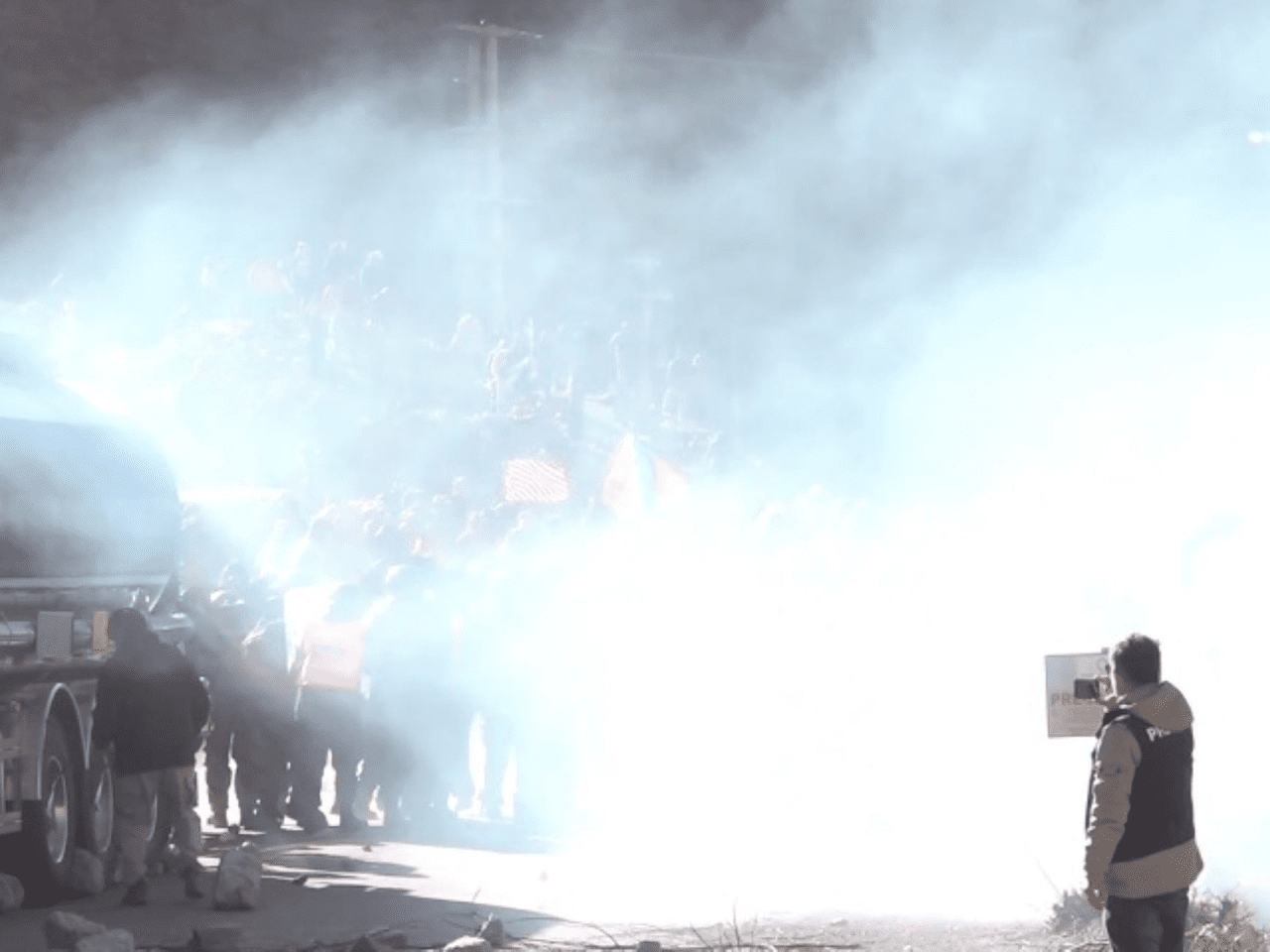

Despite everything, there comes a point when you get used to living like that. I stayed in Tepic until 2016 when they transferred me to Cefereso 16. The mass transfer proved one of the worst experiences of my life, forcing me to relive moments I wish to forget. The authorities stripped us completely naked in front of federal police, forced us to do squats until we collapsed from exhaustion, and beat our bodies.

I curled up in an onion-like position with my head bent down and my spine contorted until the pain became unbearable. Even then, I was one of the lucky ones. Others endured electrocution, their piercing screams echoing through the space.

Arriving at Cefereso 16 felt bleak. They offered no medical attention despite my severe bleeding. The gave me 15 wipes to clean myself up. Yet, in that misery, I discovered a sliver of hope. In Cefereso, I gained some basic freedoms.

I found myself imprisoned with 40 other women in an apartment-style space with a shared bathroom. Three toilets, three showers, and a common area with a television, though small, felt like a world apart from the isolation I knew previously. I could walk out of a cell again, and feel the sunlight on my skin. It brought a sense of calm I had not felt in years.

Near-death tragedy inspires prisoner into activism

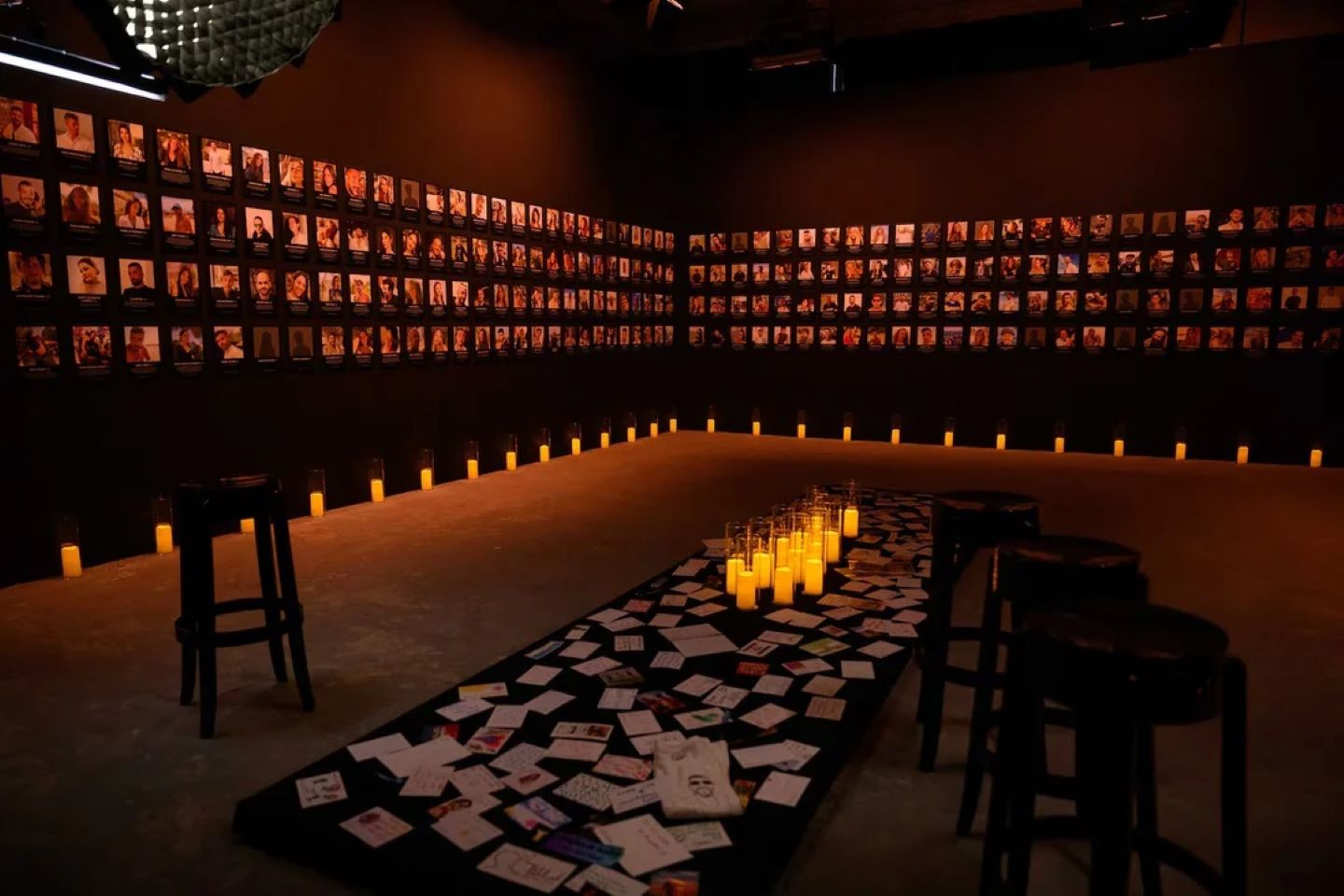

Nevertheless, being a prisoner always felt like an ordeal. The lack of emotional support, and the abandonment by family forces you to develop survival strategies, just to feel some semblance of security. In some cases, codependency develops between inmates. Couples form, and when that bond breaks, despair often leads to tragedy.

One day in December 2016, we rehearsed Christmas carols. I stepped out to use the bathroom when I heard strange moaning. I looked up and saw a friend hanging from the ceiling. My body moved on instinct. I rushed up the stairs, grabbed her feet, and tried to lift her up as best I could. I screamed for help as she began to fade, her strength nearly gone.

Several of my fellow inmates arrived, along with some officers. They stood there, watching us, telling us not to touch her, but we couldn’t just stand by. We managed to get her down. Though weakened, this woman survived. If I had not arrived at that exact moment, she would have died. That moment changed me. It pushed me into activism, to fight for better conditions for all female prisoners inside.

I spent three torturous years in that place. In 2019, they finally released me. While working in the prison’s podiatry area, treating the feet of my fellow inmates, I heard the call. “1371,” a guard shouted. Inside those walls, you are not a person; you’re just a file number.

I looked at my colleague and whispered, “I’m scared.” I had no idea why the authorities called me and I feared the worst. As I approached, they informed me of my release. I stood there frozen, uncertain how to process my time in prison coming to an end.

Out of prison: a world no longer familiar

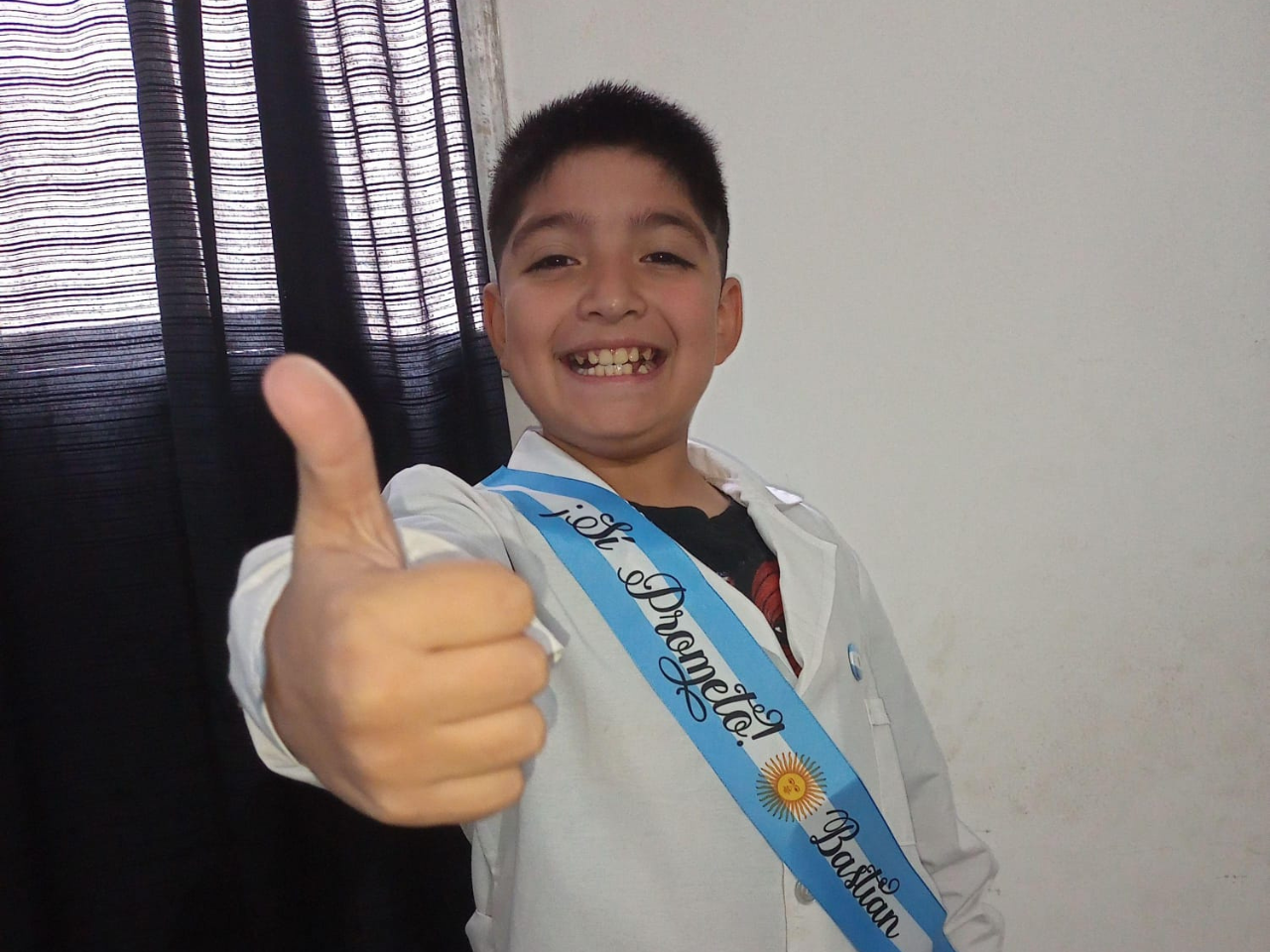

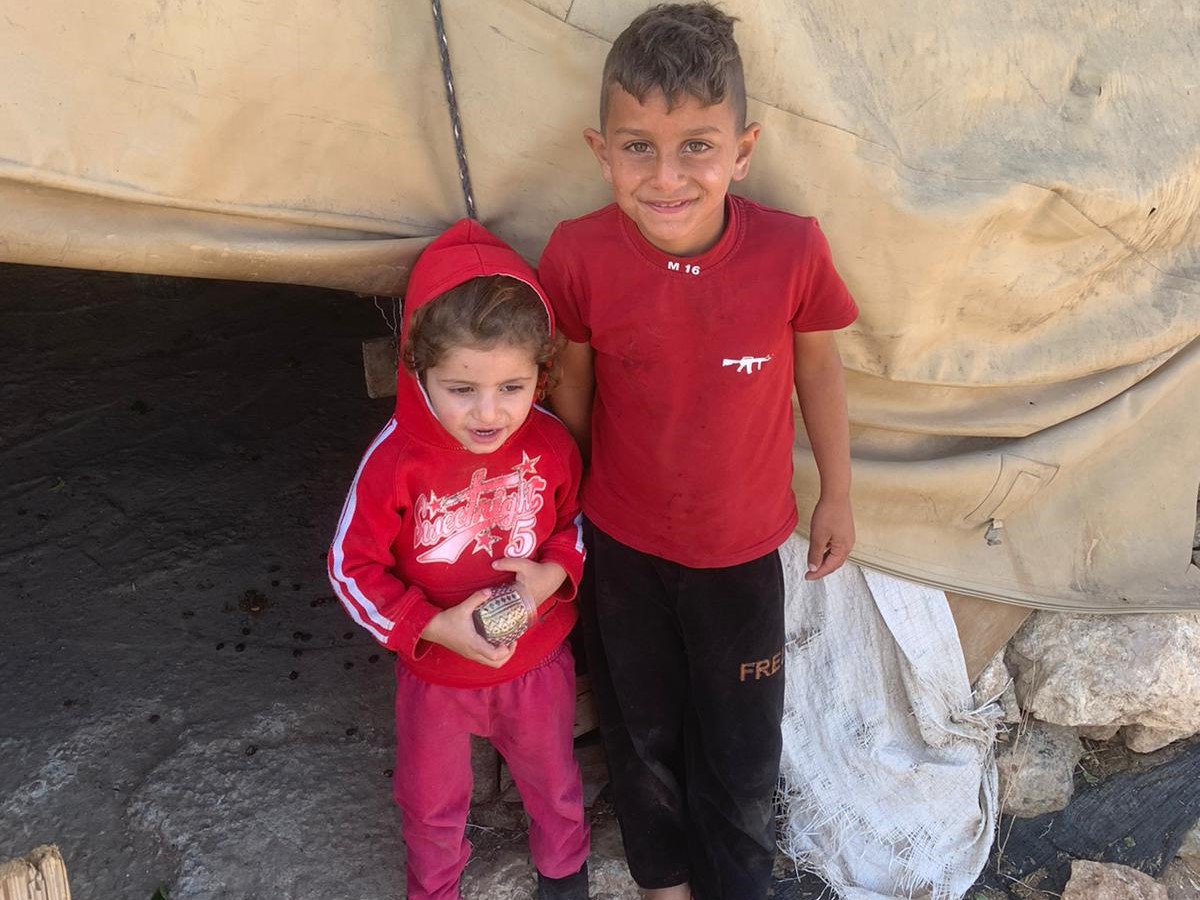

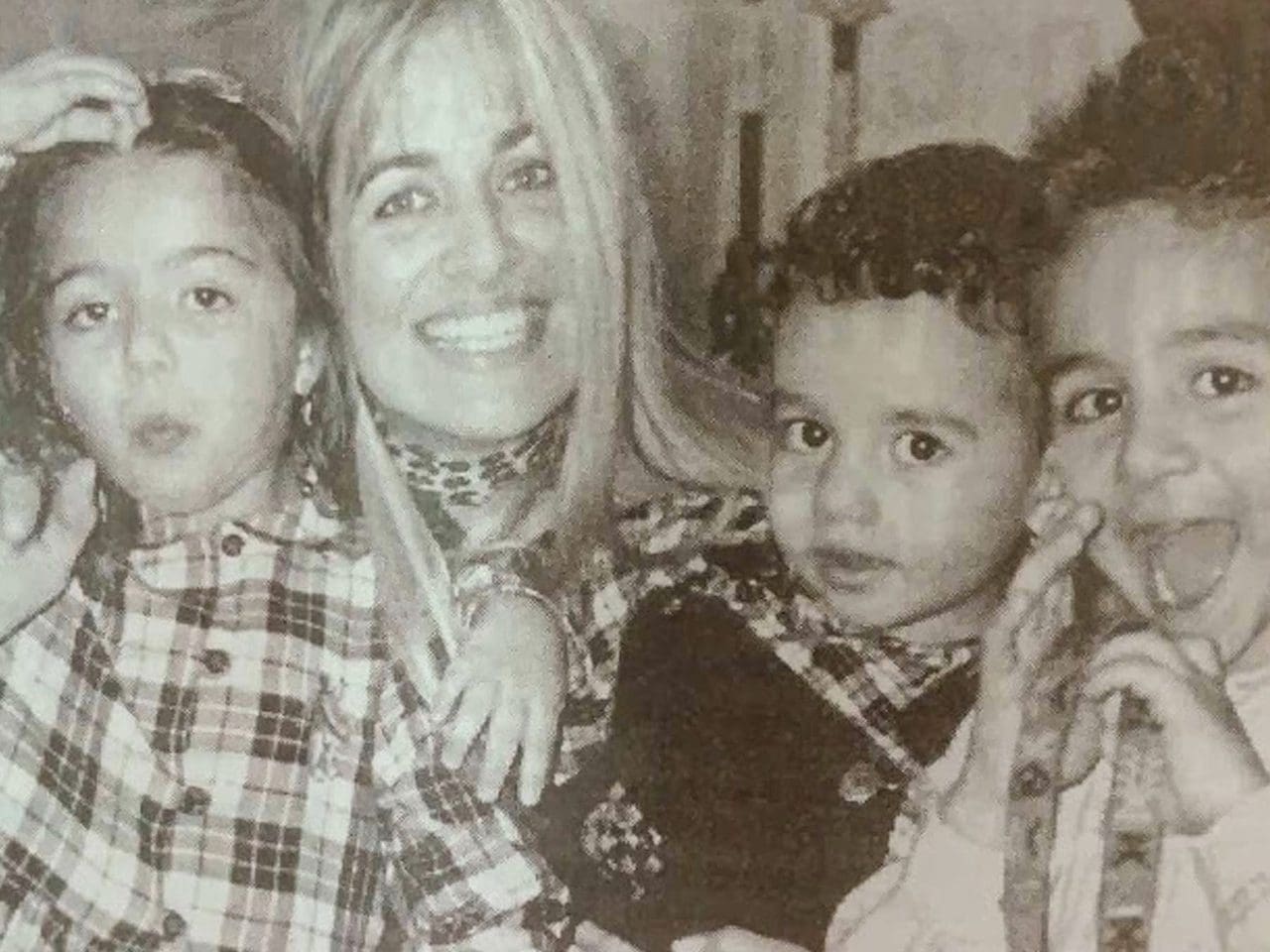

Instead of rushing out, I went back to work, tending to the feet of the 15 women awaiting their turn for care. I kept calm because deep down, I felt afraid. “What if no one awaits me on the other side,” I thought. When I finally walked out of prison, the world felt foreign. I stared at the trees like I saw them for the first time, questioning whether they were even real. Then I saw my children. They looked so different from the way I left them. Reality hit me hard.

“Are you my mom,” the children asked, “The one who used to talk to us on the phone?” The children grew used to having a mother represented by a voice on a phone. I told them yes, I am your mom, and you can come with me. Yet, I saw fear in their eyes. These children did know what to make of me – a stranger gone for so long.

Despite their hesitation, I hugged them tightly, pulling them close. That night, they slept beside me. I felt the crushing weight of all the time I lost in prison fall down upon me. I never felt it possible to return to normal life. Three days after my release from prison, the Public Prosecutor’s Office appealed, launching a new legal process to drag me back to prison.

They kept me under constant surveillance and flagged me as a risk. This prevented me from opening bank accounts or receiving money through any platform. People distanced themselves from me, and their trust in me shattered. No one seemed willing to help. The endless court hearings prevented me from keeping a regular job because I missed work too often.

Criminal proceedings came to an end, but there was no joy

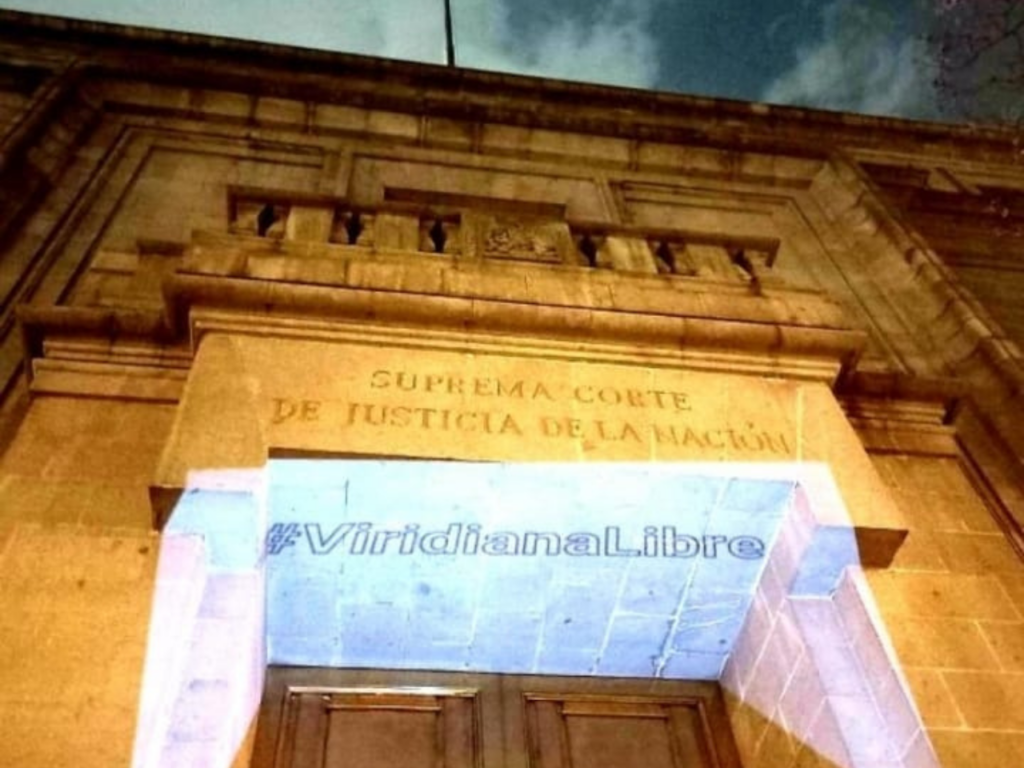

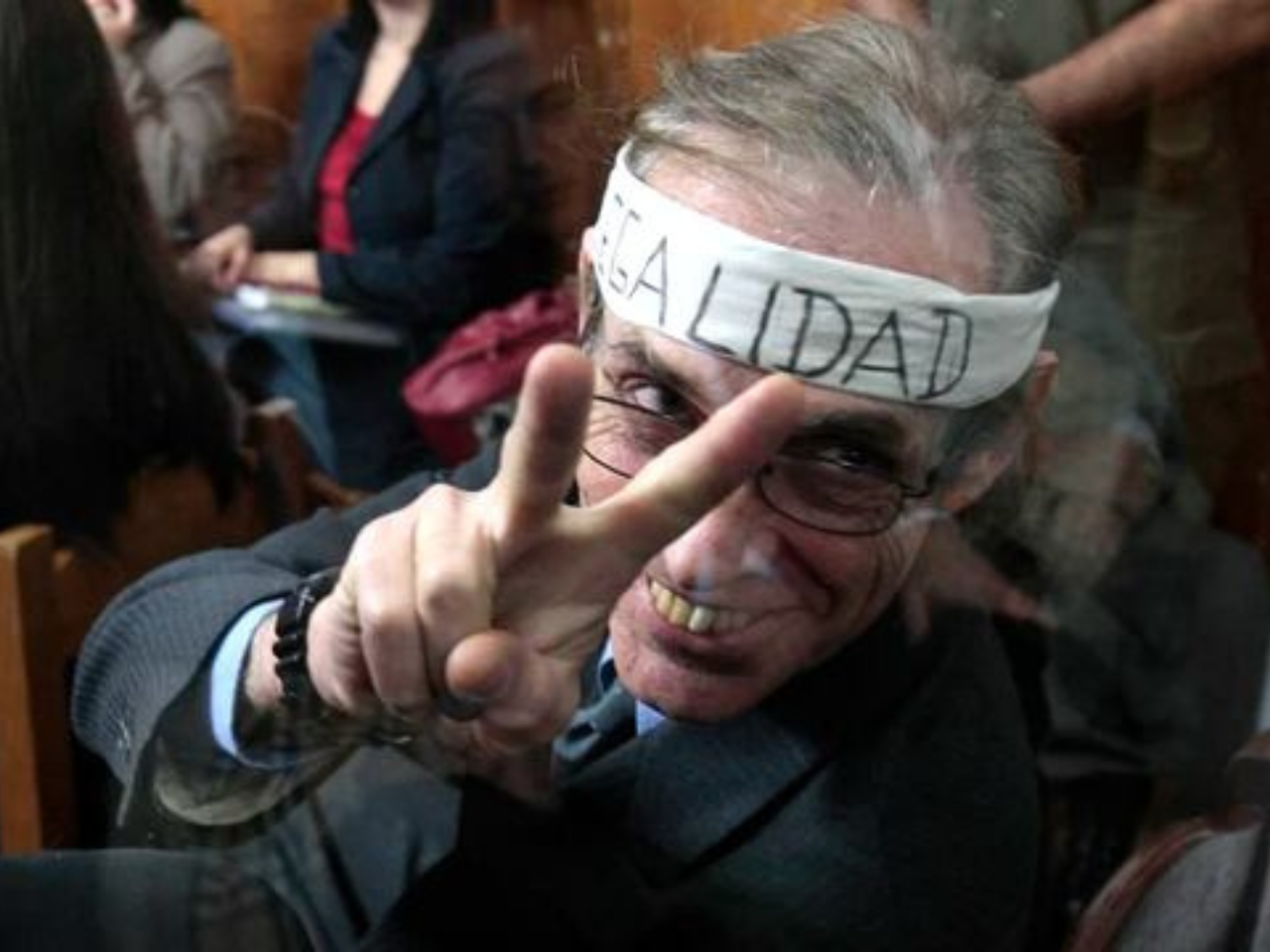

In 2021, my lawyer gave me two options: “Turn yourself in, or go on the run,” he said. By then, the authorities issued a warrant for my arrest. Yet, I refused to give in. I took control of my case, fighting the Supreme Court with the support of organizations I connected with during my activism.

While I fought to stay out, the conditions inside Cefereso 16 prison worsened drastically. A new director took over, and everything deteriorated. Intoxications became common, and deaths multiplied. Neglect and medical negligence ran rampant. I couldn’t stand by silently any longer, and I began to denounce what was happening.

At first, I felt like no one listened. Organizations with more resources, those with a privileged standing, received the attention over the individual activists. It felt like shouting into the void. The experience broke me, as a woman and a human being. The constant battle, the injustice, made me hate my country.

Just a few months ago, I received the news that the criminal proceedings against me were finally over. Relief washed over me, but there was no joy. I couldn’t resume my life, at least not the one I had before. I lost my children. They decided to live with their father because I offered nothing to them.

Today, I accept this and while I feel vulnerable, I also feel strong. Somehow, through it all, I found a deep well of motivation and energy. I feel ready to start anew. What’s lost is lost. I cannot ask my children to come with me. I have no home to bring them to. Yet, I remain here for them, walking beside them in whatever way I can.