Exiled in silence: news correspondent suddenly departs Russia

As I entered the Ministry of the Interior building, the familiar face of the person who typically assisted me remained conspicuously absent. Instead, a man I never saw before summoned me to a different window. “You are on a list of people whose visas will not be renewed,” he stated bluntly. I felt taken aback. Though I had anticipated this moment, I never expected it so soon.

- 2 years ago

May 14, 2024

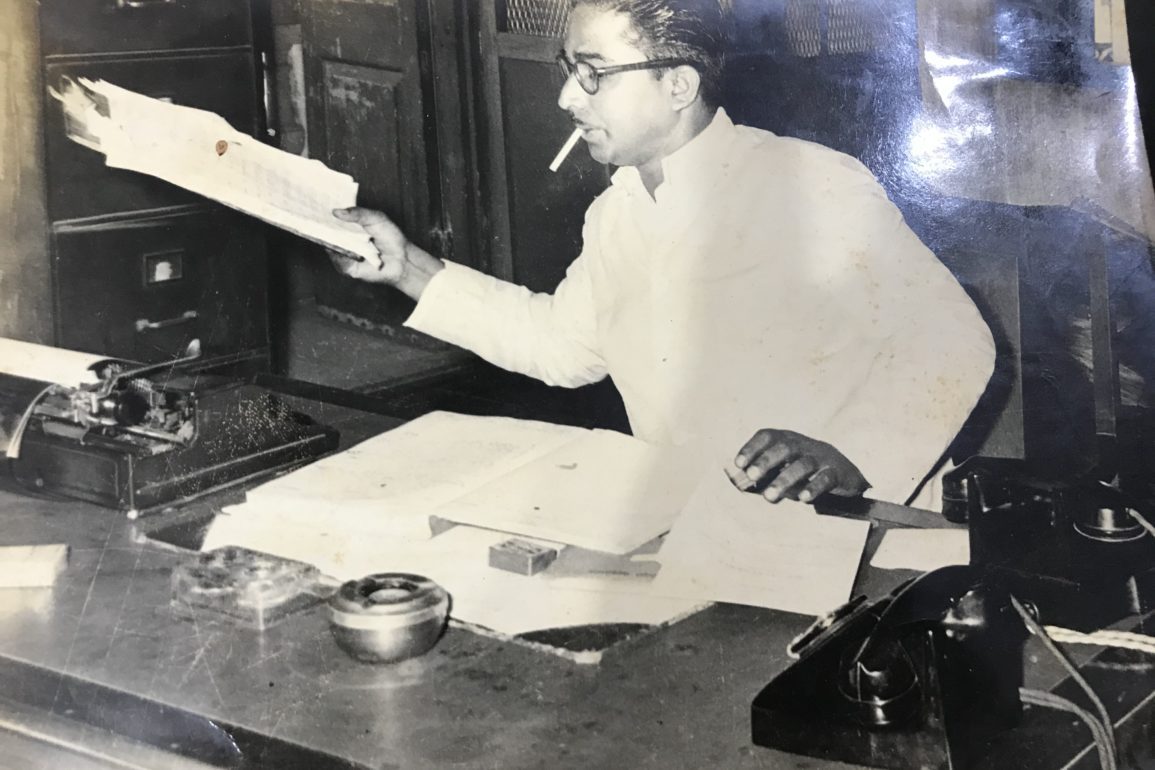

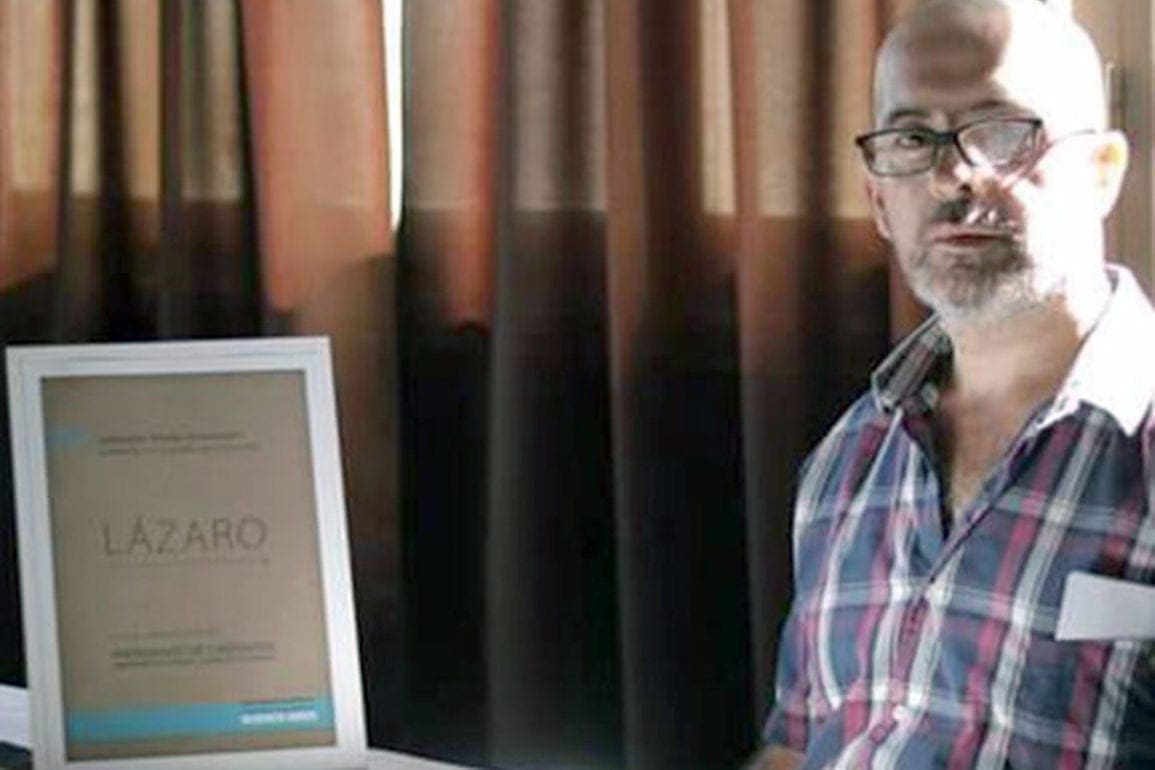

MOSCOW, Russia — I spent 12 years working as a news correspondent in Russia. From the moment I arrived in Moscow, it felt like home. Still, I knew my presence remained at the discretion of my host country. With a duty to my profession and to reporting the realities of society, I can be an uncomfortable guest, unwilling to conform to saying what is expected. This commitment led to my ultimate expulsion from an increasingly insular Russia.

Read more stories from Russia at Orato World Media.

Russian police visit correspondent’s home: “I felt I was under surveillance”

In January 2024, while on my way to Finland to cover the elections, my world took an unexpected turn. My phone rang and I heard a friend’s voice. “The police have visited your home looking for you,” he said. For a long time, I anticipated that message. I felt for some time I may be under surveillance. “It’s finally happening,” I thought, as a sense of vertigo set in. I wondered about the possibility of being detained at the border.

Approaching the immigration checkpoint with a mix of nerves, I calmed myself by reasoning that I wasn’t significant enough for an arrest warrant. I resolved to continue with my trip as planned. As I processed the news and contemplated my next steps, the thought of not returning to Russia briefly crossed my mind.

It felt like one of those moments when your brain goes into overdrive, sketching out various action plans. “Don’t let fear guide you,” I told myself, mustering the courage to go back home, despite friends advising against it.

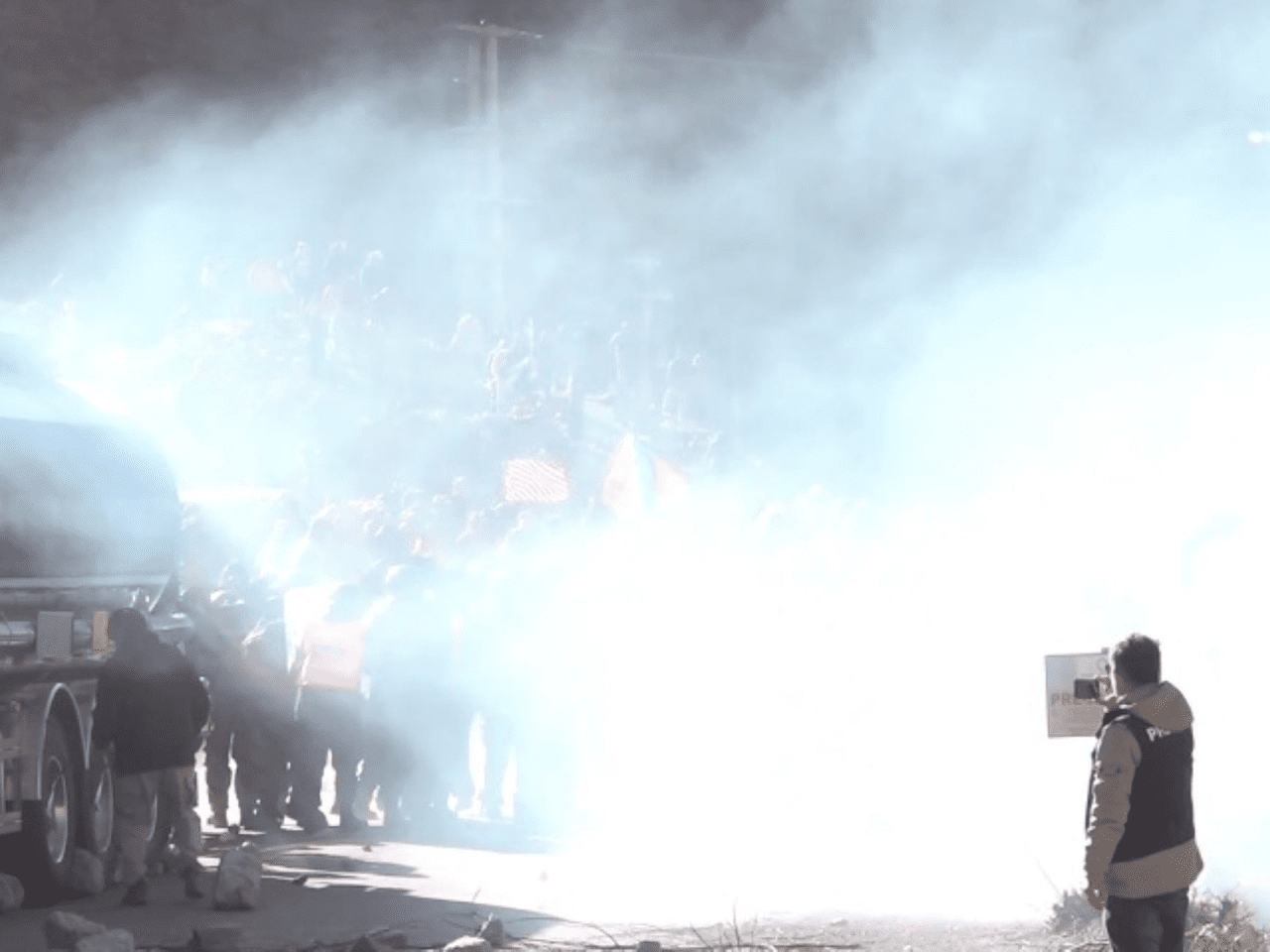

At that time, I was covering protests by the wives of Russian soldiers against the war in Ukraine. The Russian government, known for its swift crackdowns, opted not to detain these women to avoid public outcry, focusing instead on intimidating journalists like me. Since the war began, I renewed my visa every three months. Typically, the Russian government provided the necessary documents for renewal at the last minute.

On March 19, 2024, just one day before my visa expired, I received my accreditation from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. With the document in hand, I went for what should have been a routine bureaucratic procedure to continue my work. They instructed me to return in the afternoon, and I complied.

Russia will no longer renew correspondent’s visa: “We don’t owe you any explanation”

As I entered the Ministry of the Interior building, the familiar face of the person who typically assisted me remained conspicuously absent. Instead, a man I never saw before summoned me to a different window. “You are on a list of people whose visas will not be renewed,” he stated bluntly. I felt taken aback. Though I had anticipated this moment, I never expected it so soon.

I sought more information, but the man stonewalled me. “We don’t owe you any explanation. Your visa expires tomorrow, and I recommend you leave the country earlier to avoid problems,” he advised. With sweaty hands, I stepped back onto the street, contemplating the complexities of a quick departure from Russia. Flights remained scarce, especially with European skies closed to Russian flights. As I headed home, I reached out frantically to colleagues, friends, and my bosses at The World for support and advice.

Suddenly, I found myself living the kind of story I usually reported on from a distance. As the Russian state began drafting people for war, many Russians fled the country. They told me how they searched online for tickets, choosing the anywhere option as their destination. I never imagined I would be doing the same, hastily searching for a flight to an undefined location, desperate to leave what had been my home for over a decade.

Fortunately, I managed to secure a flight to Istanbul the next morning. I spent the ensuing hours shredding documents and organizing my belongings into categories. I sorted the essentials like my computer, iPad, and Kindle; items a friend would send later; and things to discard. Living as a correspondent taught me to keep possessions to a minimum, ready for moments like this. Twelve years of my life became compressed into three suitcases.

As the plane took off, I watched Russia fade into the distance, its vast, snowy landscapes shrinking in the distance

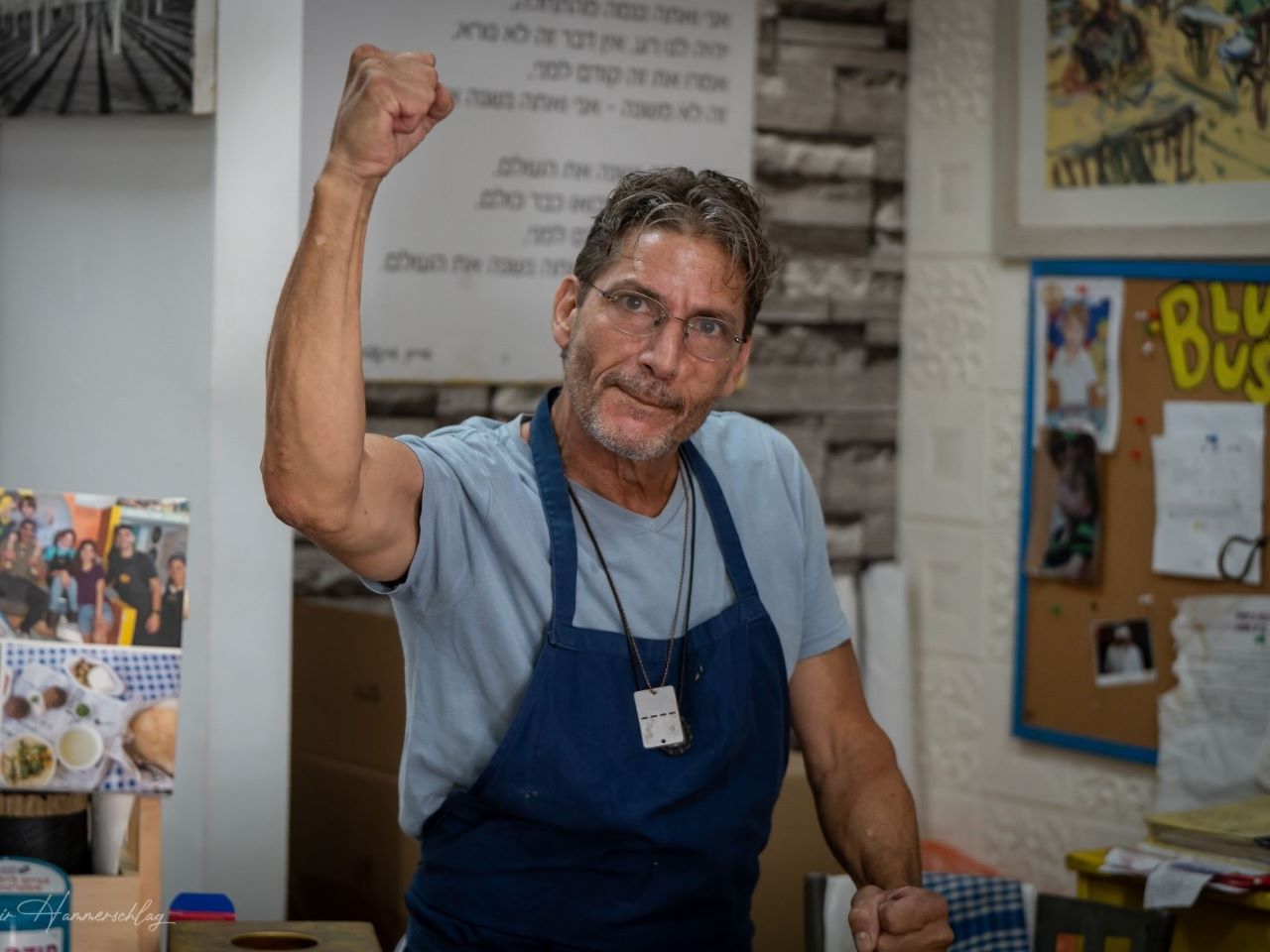

I invited colleagues to one last dinner and kept the bill as a memento of the life I could be leaving behind forever. The melancholic undertone, combined with the intense adrenaline and numerous tasks I faced, left me little time to dwell on my departure. After managing only three hours of sleep, I headed to the airport early in the morning.

At the check-in counter, my nerves kicked in as I presented my passport and proceeded to the gate. Once on board, I sighed in relief and sent messages to reassure loved ones that all was well. My final message to a friend who remained in Moscow felt like the hardest to send. I thanked him for his profound friendship as a lump formed in my throat. That painful moment marked the whirlwind I was caught in.

As the plane took off, I watched Russia fade into the distance, its vast, snowy landscapes shrinking behind me. While I felt the happiest in my life in Moscow, the region simultaneously presented the most challenging place I ever reported from. My life there included a blend of feeling at home, while always knowing I might have to leave.

When I first arrived in Russia in 2012, my foreign accent opened many doors. On my first day, someone offered me a job teaching Spanish, and I frequently received invitations to contribute to state media. That marked a time when the media was still known for journalism, not propaganda. I felt warmly welcomed, embraced by a culture vastly different from my own. This complex relationship with Russia shaped my years there, filled with enriching experiences and difficulties.

The knowledge that I have remained true to my journalistic duties comforts me, and I will continue to do so without regret

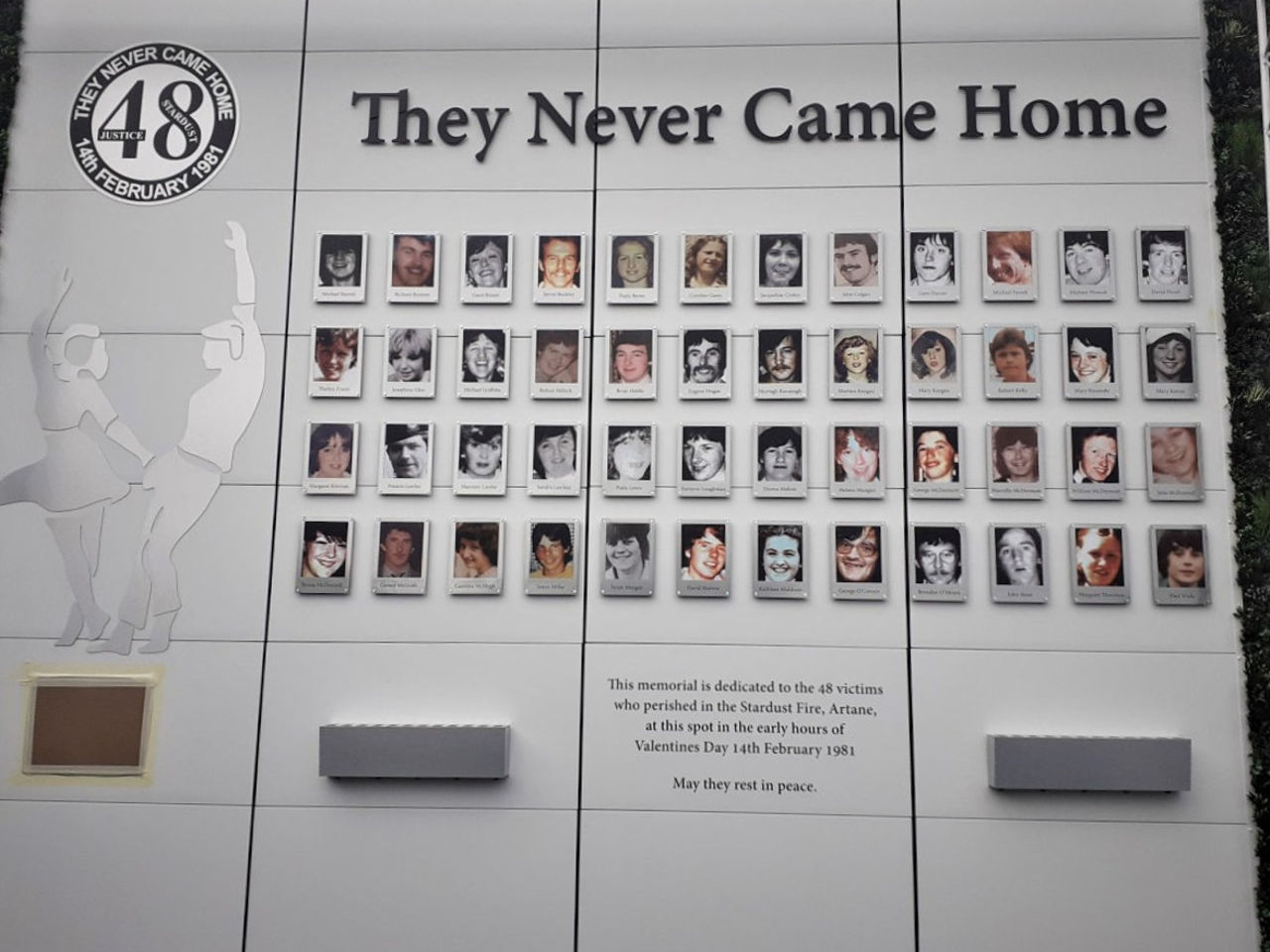

Two years after arriving in Russia, the war in Donbas altered everything. I considered Russian actions illegal, contrasting sharply with many locals who viewed them as a sacred duty. This polarized perspective fostered an “us versus them” division, with me squarely among “them.” Over time, a government-fostered fiction took root in society, gradually becoming an accepted reality.

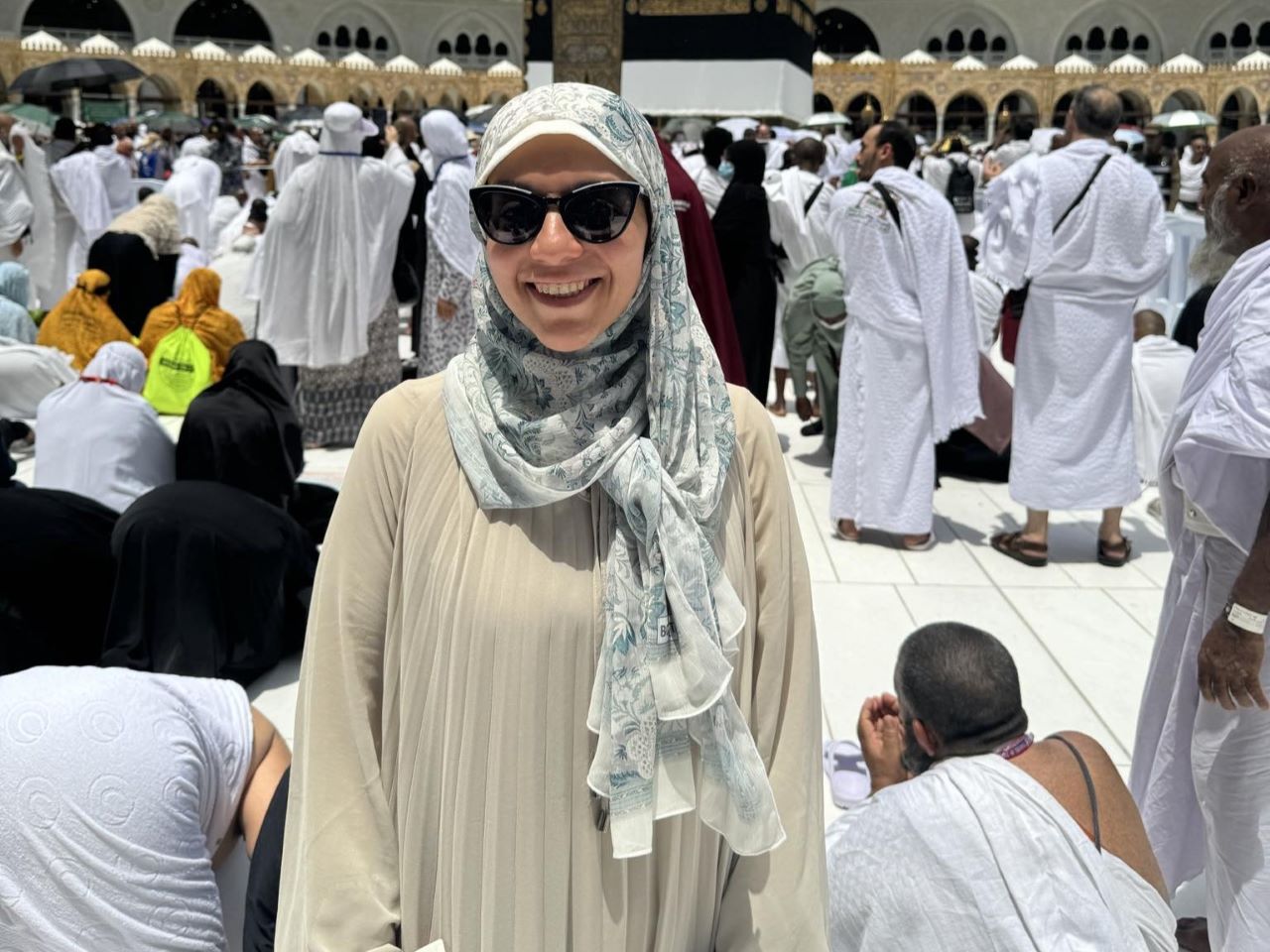

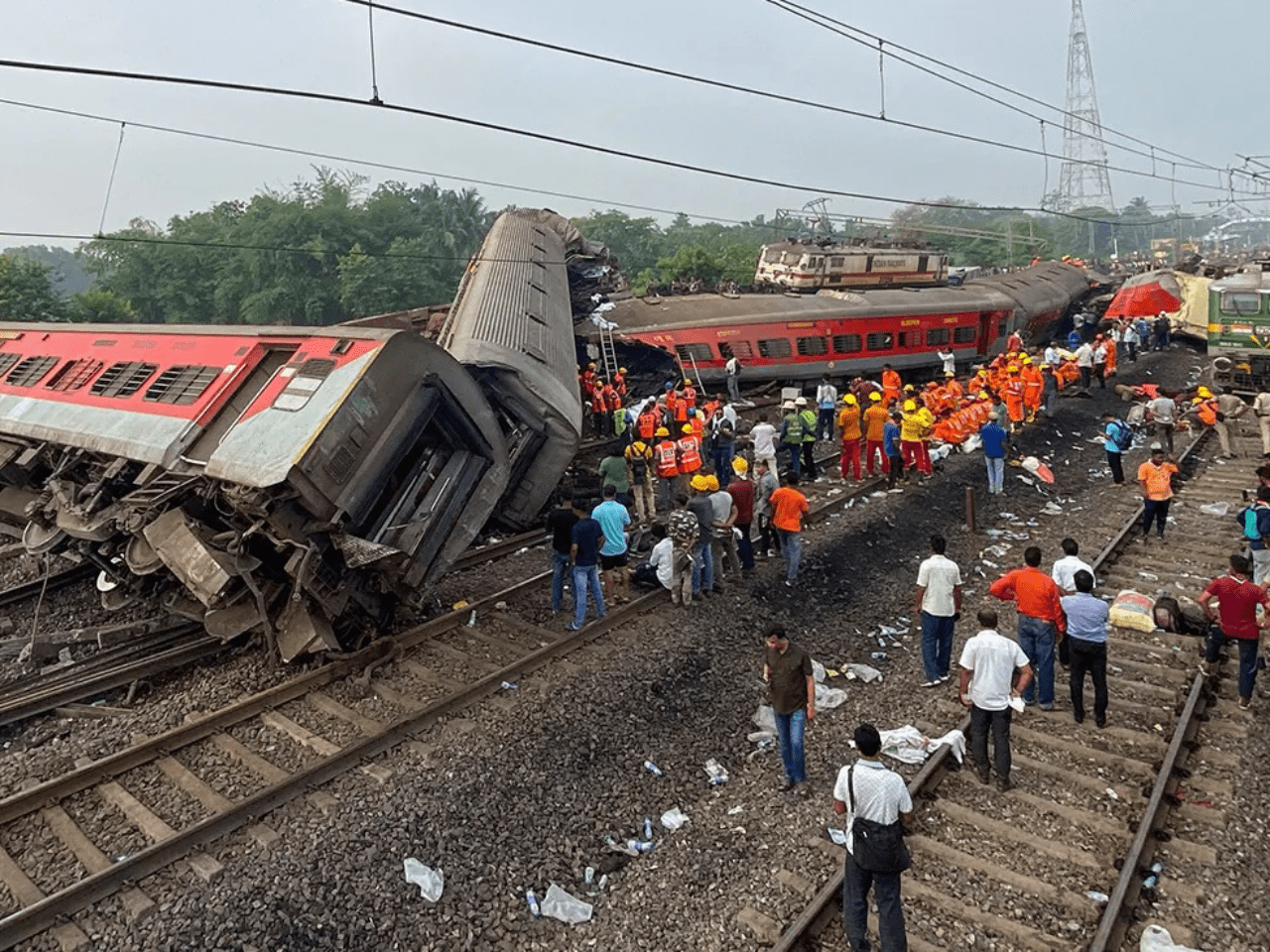

When the Russian invasion of Ukraine commenced, I was in Kyiv. The sound of distant shelling awoke me. With each lull in the shelling, I braced for closer impacts. Despite the danger, I engrossed myself in reporting, undistracted by the chaos. I felt more concerned with losing time and missing important stories than with running out of Wi-Fi or finding food and water. The urgency of reporting felt so compelling, like an exhilarating rush driving me from one task to the next.

That moment underscored Russia’s detachment not only from the Western world but from reality itself. The embrace of fanaticism and force normalized absurdities, a change starkly evident upon my return to Moscow. Friends posted pro-regime content, and others, previously indifferent to politics, fled to avoid conscription. It became a vivid illustration of how quickly politics can become unavoidable in our daily lives.

Reflecting on these events, I realize how profoundly history can touch us. We are all shaped by the narratives we consume, but it’s often not until we experience history personally that we fully understand its impact. This experience shifted my location and my life. Yet, through it all, the knowledge that I remained true to my journalistic duties comforts me, and I will continue to do so without regret.