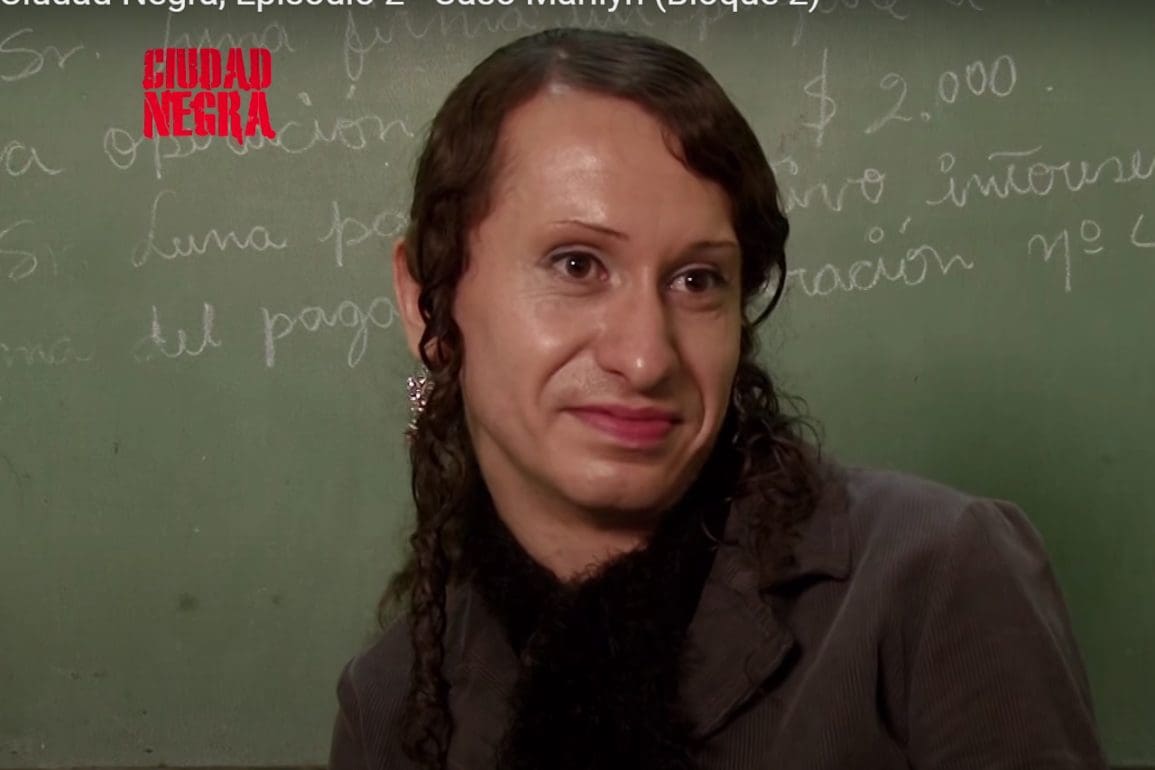

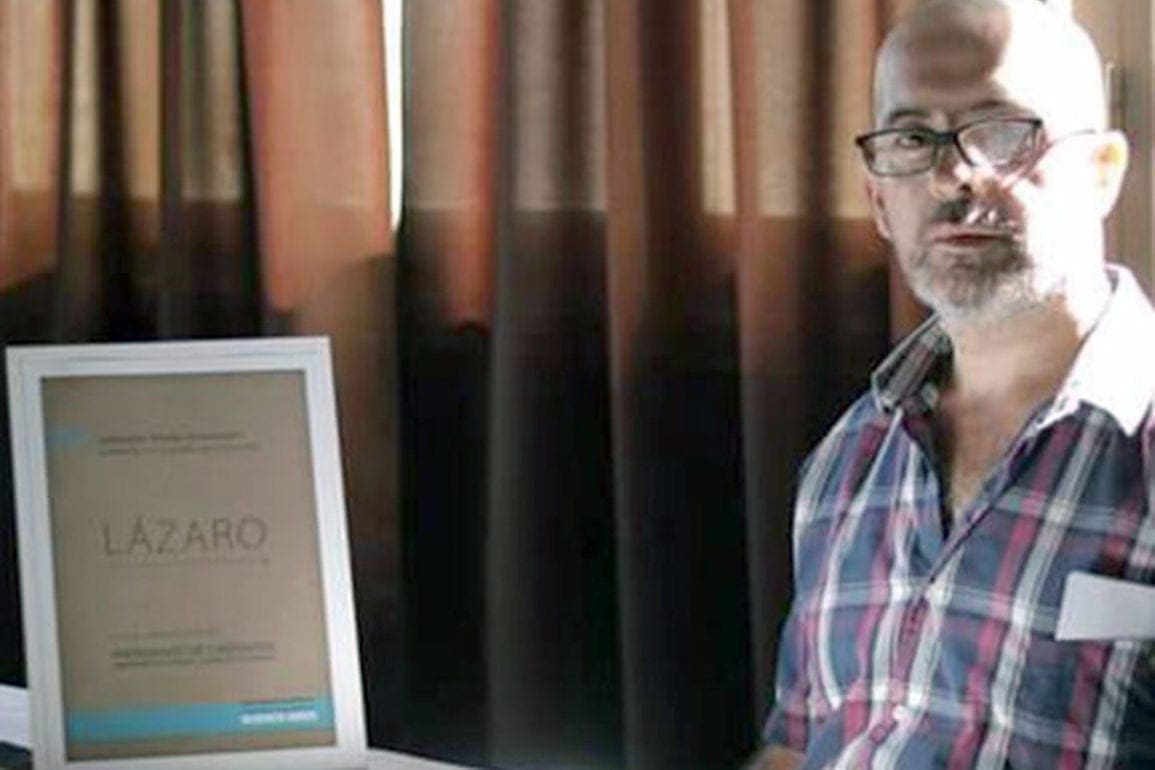

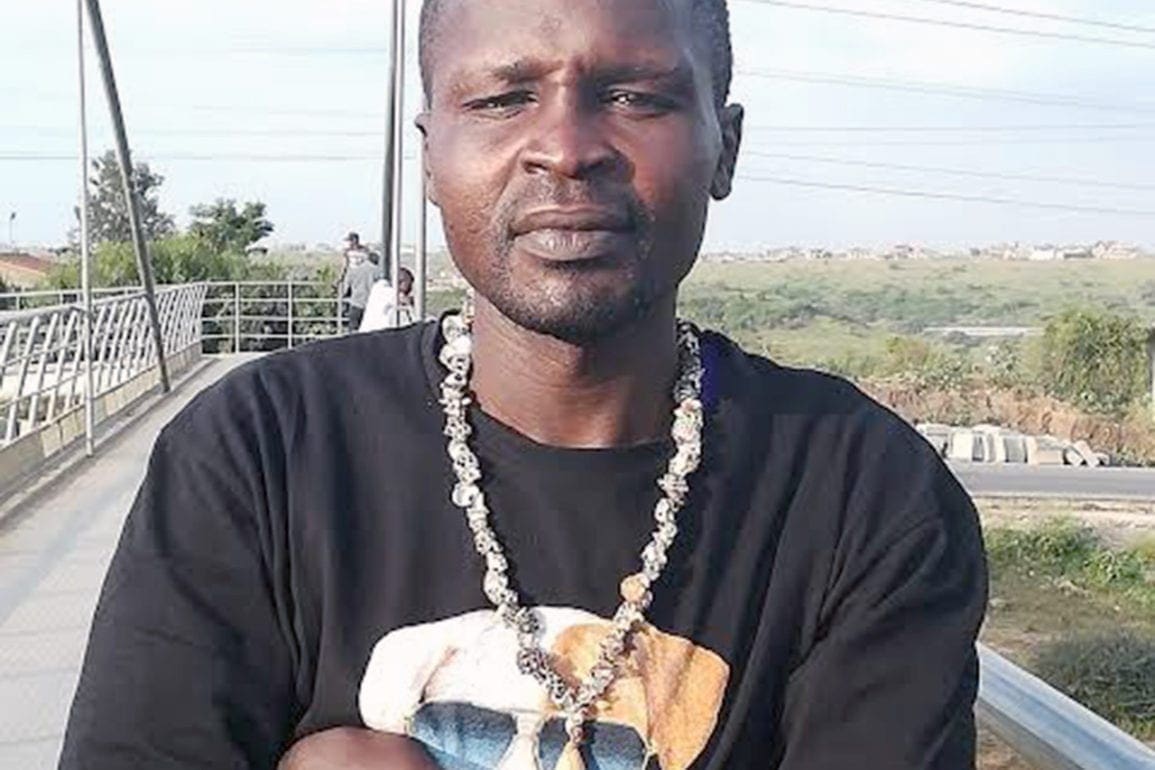

He became the face of the 33: speaks out on police raid of gay bar in Venezuela

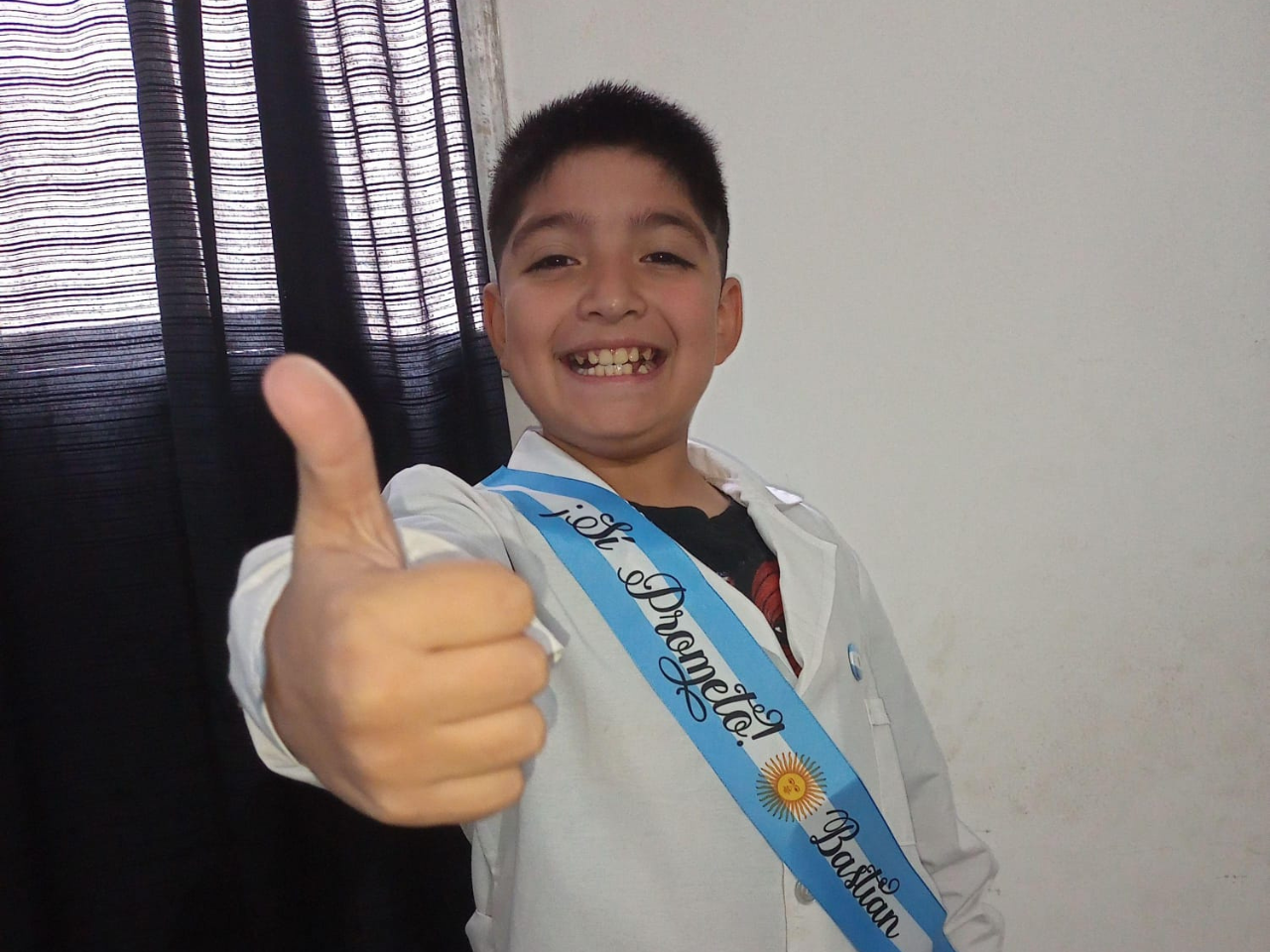

I have a 10-year-old son who, until recently, dreamed of being a policeman. The uniform, the power, and the promise of taking care of people attracted him. After this incident, seeing how it affected me, he changed his mind. One day, he came to me and said, “Dad, I don’t want to be a policeman anymore. I don’t want to be bad.”

- 2 years ago

September 13, 2023

VALENCIA, Venezuela — On a Sunday afternoon after work, I joined some friends to have a drink at Avalon Spa & Bar, a local LGBTQ+ establishment. For the first 20 minutes everything seemed find, then we heard a shout from the door. “Comando de la Policía Nacional Bolivariana,” they shouted, announcing themselves. “Hands up, stay where you are!”

I ignored the shouts at first, thinking it was a bad joke, but seconds later uniformed officers forced their way in holding weapons. Extreme stress flooded my body as I struggled to understand. Everyone around me appeared confused. The officers herded us to a locker area beneath the spa’s steam room. “Nothing will happen to us,” I thought. “We didn’t break any rules. We were simply having a drink.”

Unease and restlessness made its way through the crowd as they demanded our documents and let some people leave. Those with important contacts or who worked for the government could go. The rest of remained hostage without explanation. I began to fear what was next.

Read more LGBTQ+ related stories at Orato World Media

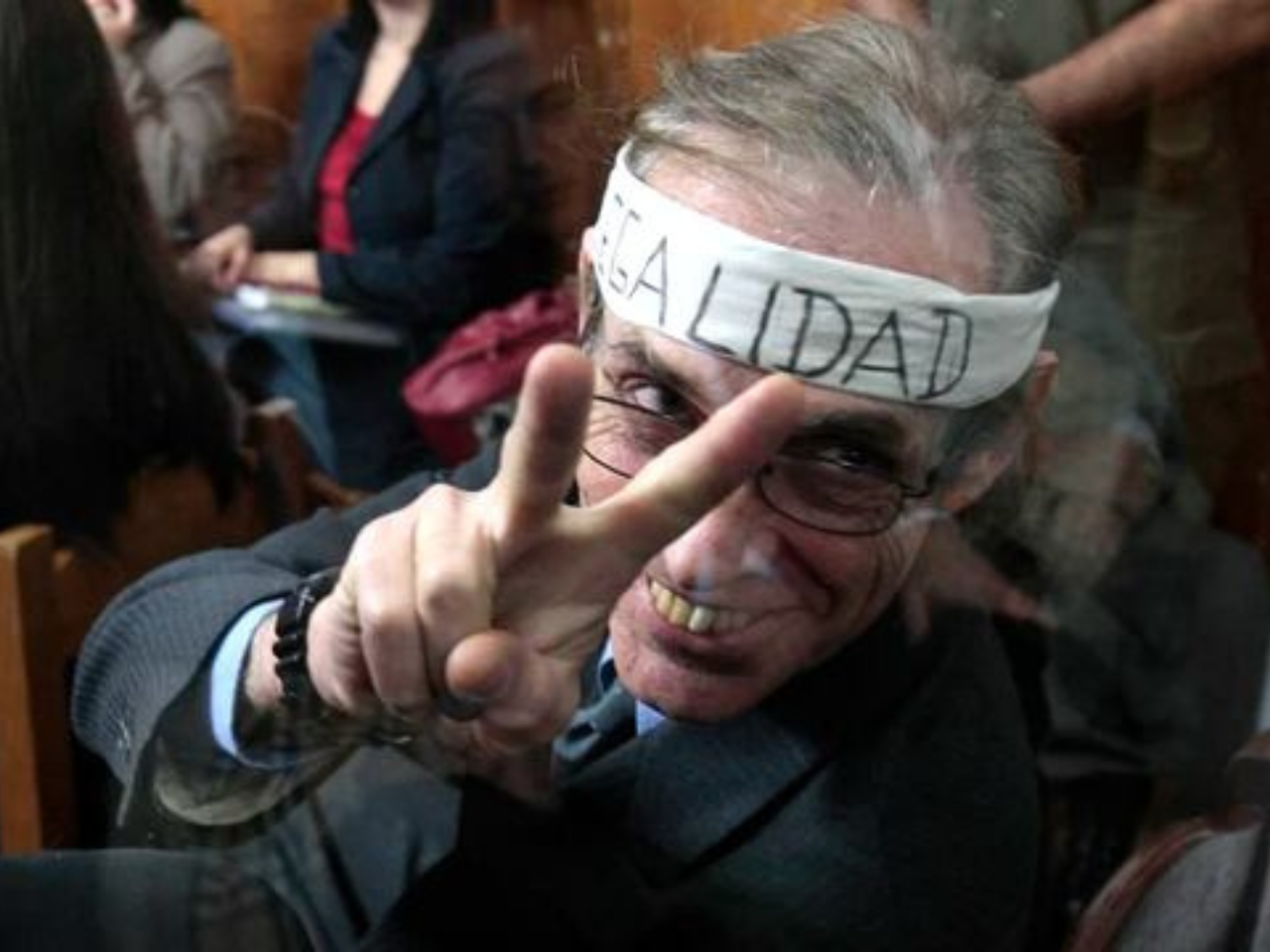

Detained, humiliated and taunted

We looked around the room for reassurance, unable to grasp the gravity of the situation. The police indicated we would be transferred to a command far from the spa and bar; that we were witnesses and this was a routine procedure.

“Get in the vehicle,” they ordered, and started driving. The ride felt strange, despite the friendliness and jokes from the officer behind the wheel. As the station drew near, our tension level escalated. The minute we arrived; the situation took a sharp turn for the worse.

The friendliness from the officers ended immediately. They seated us in a large office, preventing us from talking to one another or leaning against the wall. I saw fear in the eyes of the detainees and I felt scared and nervous. I tried my best to remain calm so I could support the rest of the group.

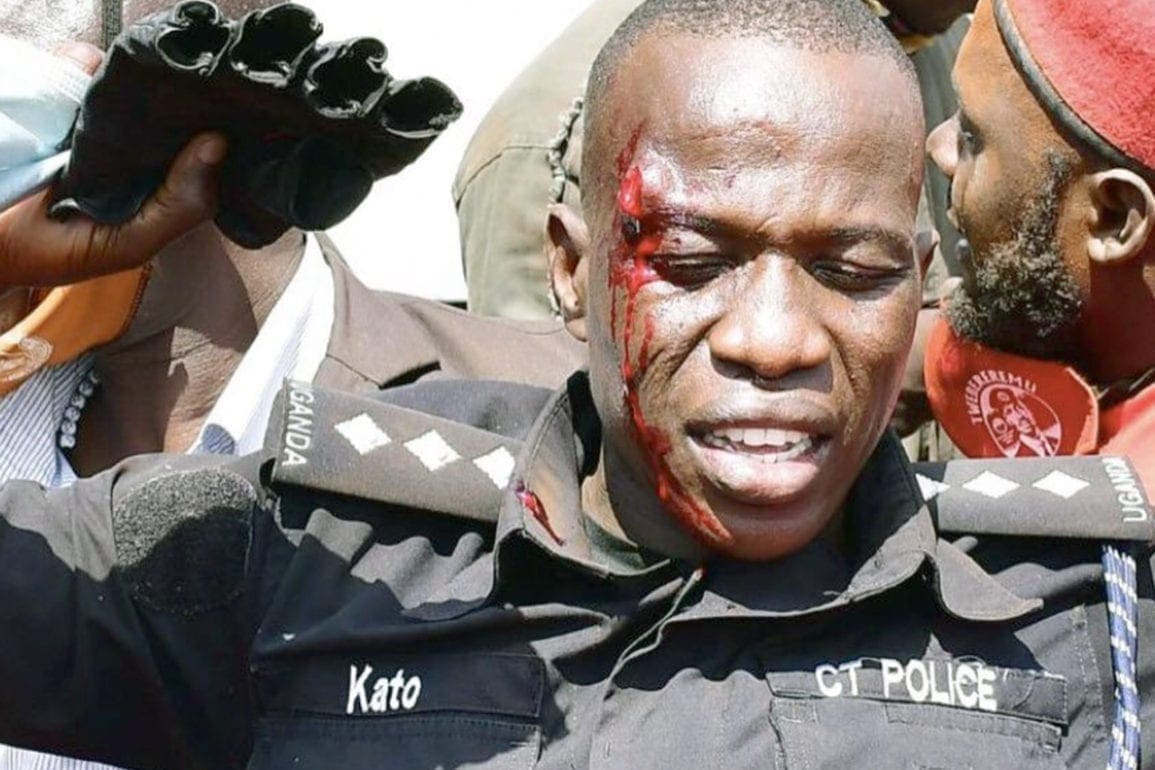

No one expects something like this to happen to them, but these kinds of incidents have become more frequent in my country. Police officers here do what they want without accountability, taking bribes in exchange for your freedom. It feels like kidnapping.

During the wait, I started thinking maybe this was one of those situations, and we would soon be free. Moments later, they marched toward us and took away our cell phones. The other detainees started sweating and hyperventilating. The atmosphere became hostile.

Feeling overwhelming, I fought hard to hide my fear. To be gay in Venezuela means you are constantly subjected to homophobia. An officer asked us to unlock our phones and rifled through our private photos and videos, commenting on them out loud and laughing with her colleagues. Some of the detainees, broken by the stress, began to cry or nearly fainted.

They wrongfully charged us and spread lies on social media

I focused on watching everything carefully, recording the scenes in my head so I could talk about it in detail later, if I had the chance. The unbearable stress gave me an intense, stabbing stomachache. I asked several times to use the bathroom. They eventually allowed it, under one condition: an officer watched me the whole time. Sitting on the toilet with the door open, the policeman laughed and pointed. The humiliation burned inside of me.

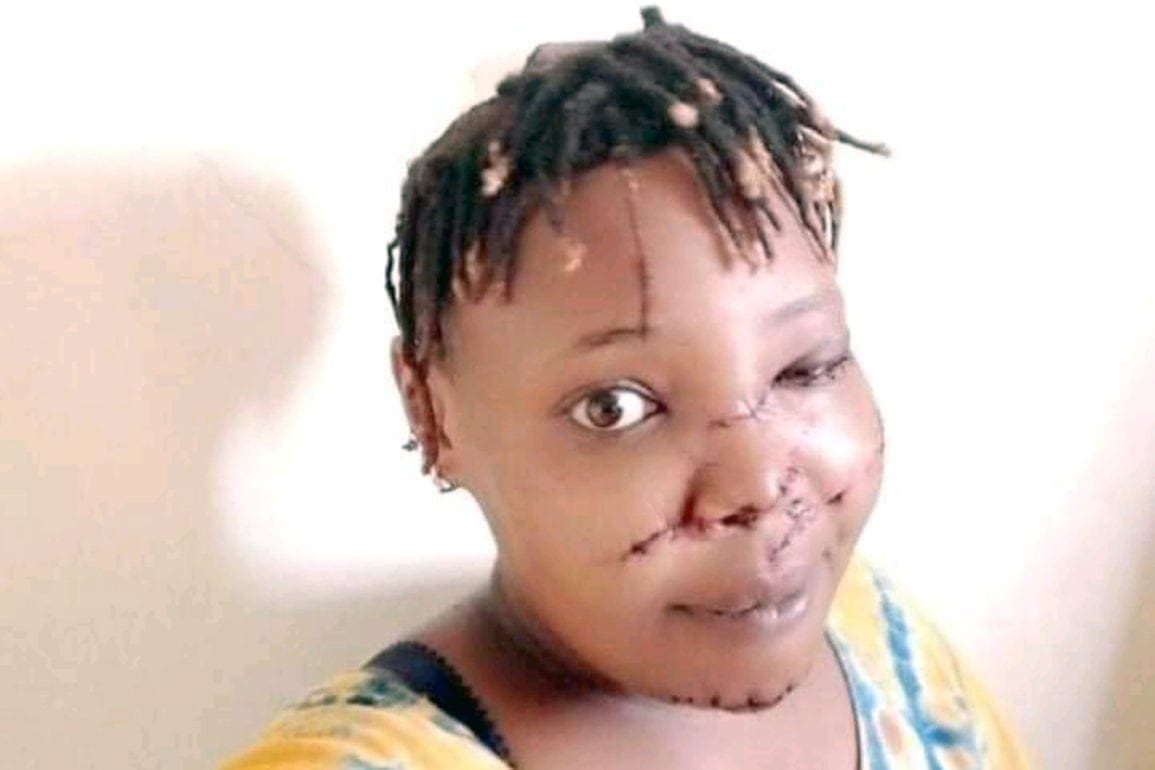

Afterwards, they returned me to the group and continued to make fun of us. I felt ashamed. Although we didn’t know it yet, they already plastered our faces on social media. The posts went viral, claiming an alleged orgy that never happened. They even accused us of having minors present. It made me sick. We spent that night in jail, charged for crimes not communicated to us. Some of the men were married or in the closet and began talking about suicide.

The hours seemed to last forever. No one slept and we felt the effects of fatigue, fear, and hunger. The next day, they finally gave us food but kept us imprisoned until Wednesday. Upon our release, we faced charges of indecent assault, illegal gathering, and noise pollution. Though we regained our freedom, we felt violated and dehumanized. The false accusations made against us circulated social media networks adding to our embarrassment.

Our everyday lives changed drastically

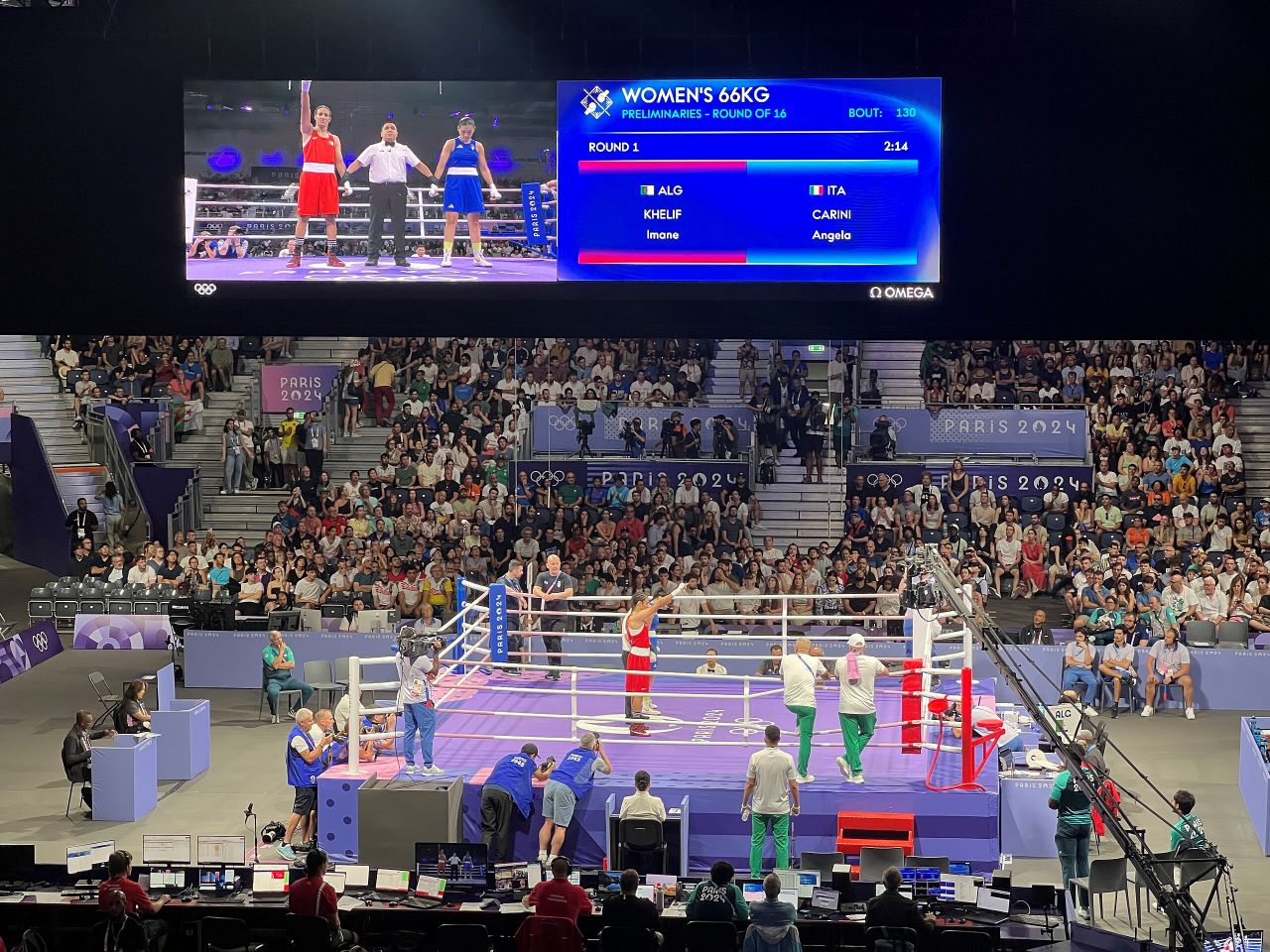

People in the LGBTQ+ community in Venezuela face difficult times. The most popular politicians rile up conservative religious groups in our country; groups that hate our very existence. We live in constant fear, feeling less protected than ever. The world seems not to care.

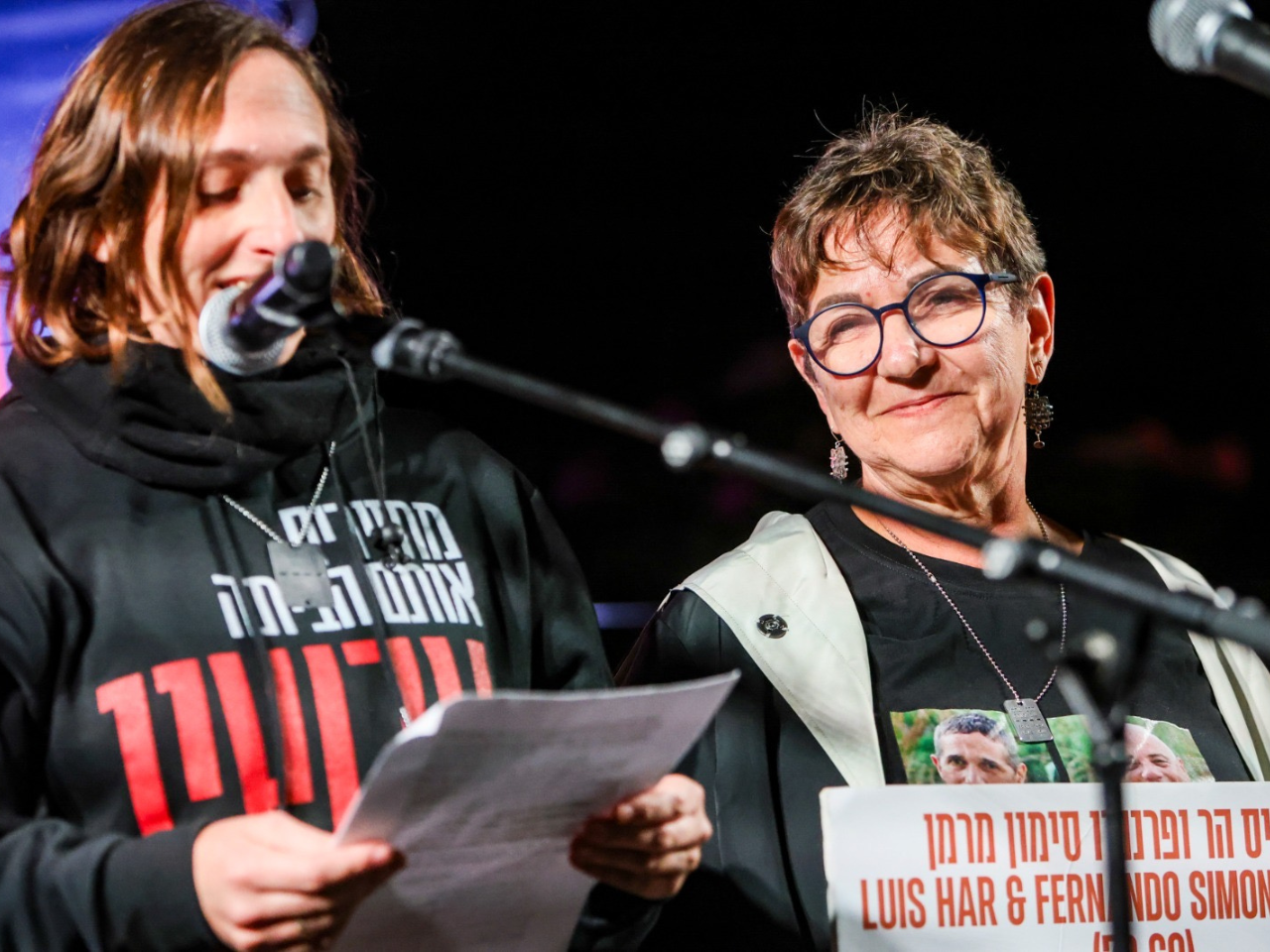

The people imprisoned with me remain traumatized. Some lost jobs or were kicked out of their homes. I decided to testify and become the face of this case so I could represent them. Soon after, I faced my own consequences. One afternoon, while sitting in a restaurant waiting for a friend, I heard two women talking behind me. One of them said, “Look, it’s the boy from the orgy.”

Instantly, my hunger vanished, and I felt a deep urge to insult her. Instead, I took a deep breath, greeted her politely, and walked away. It made me sad, because I led a normal and peaceful life before this. Now, strangers feel entitled to say hurtful things to me on the street.

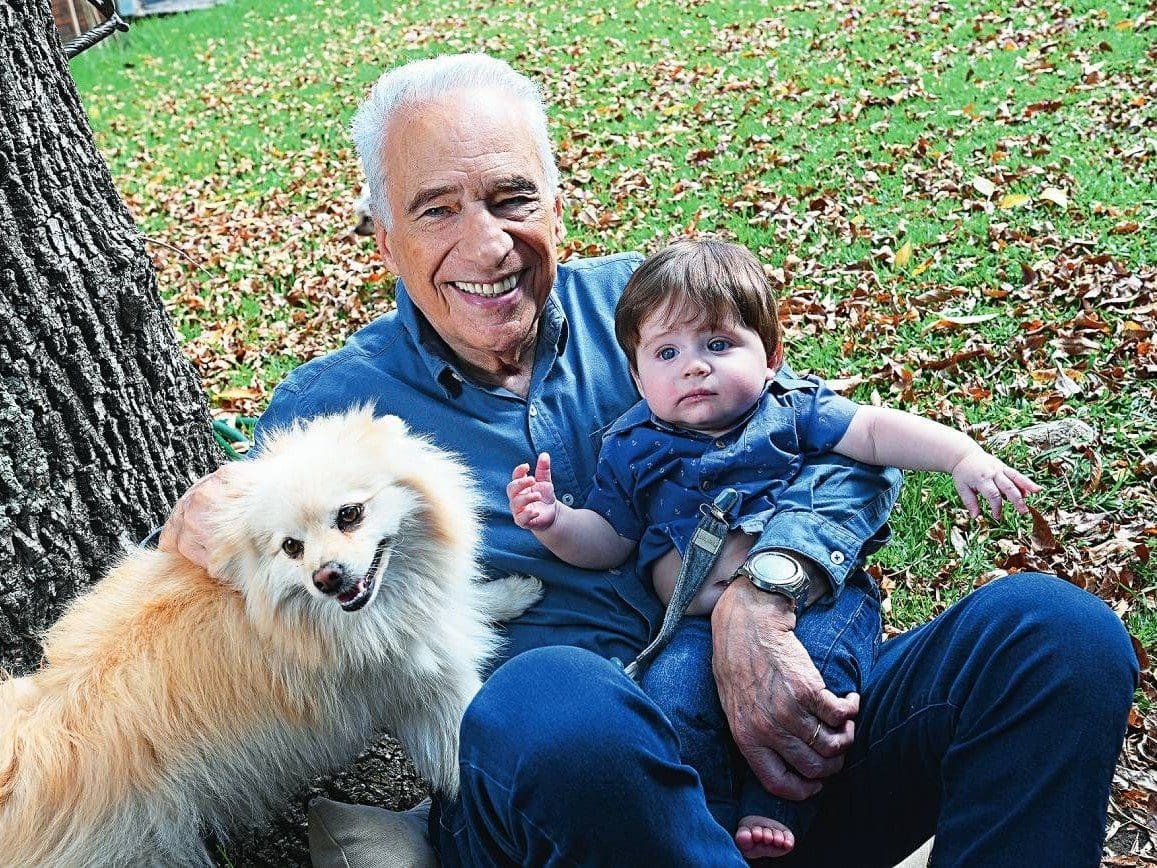

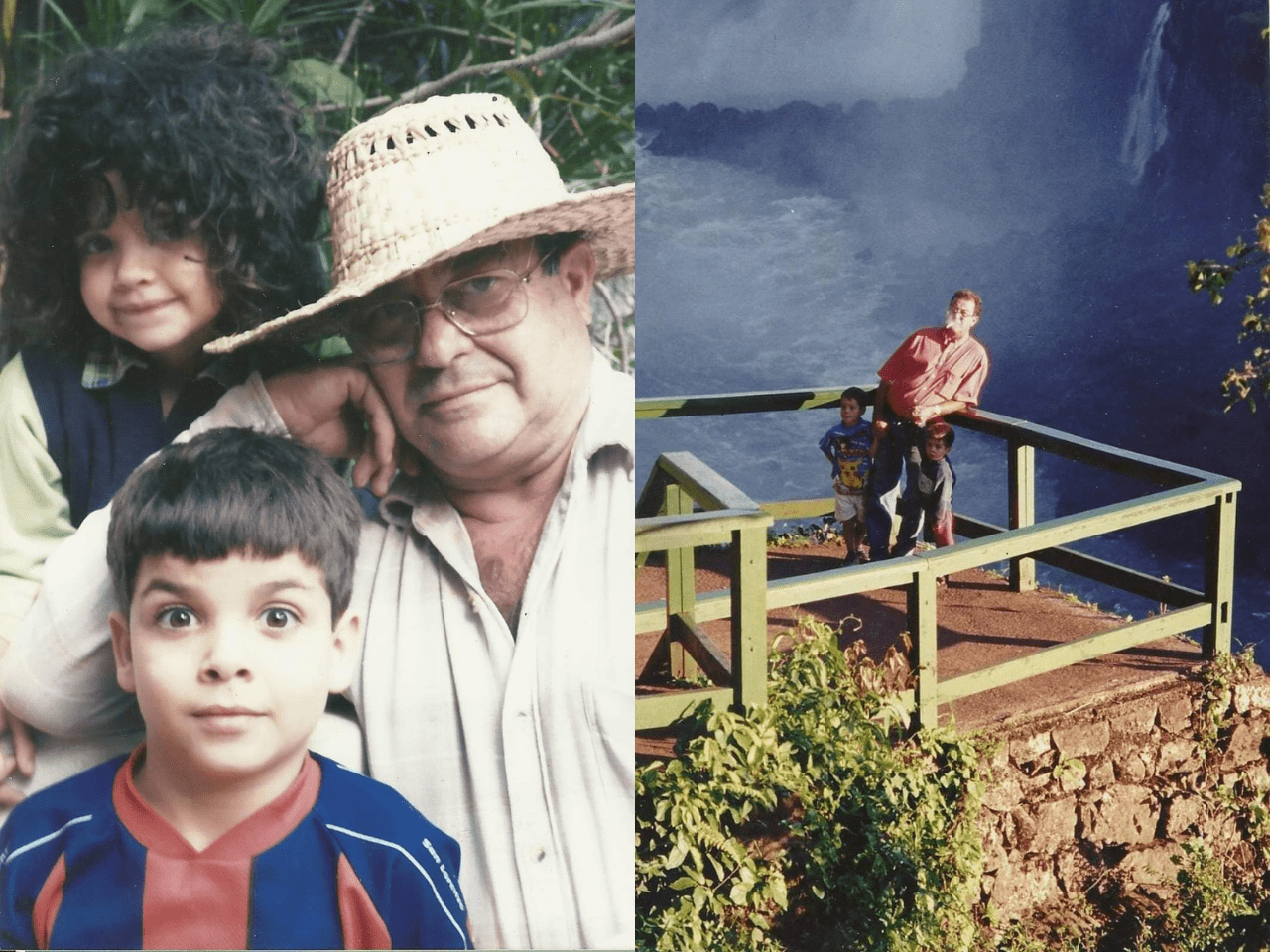

I have a 10-year-old son who, until recently, dreamed of being a policeman. The uniform, the power, and the promise of taking care of people attracted him. After this incident, seeing how it affected me, he changed his mind. One day, he came to me and said, “Dad, I don’t want to be a policeman anymore. I don’t want to be bad.”

We remain motivated to fight for our community no matter what

It saddens me that those meant to protect us cause suffering. It shouldn’t be this way. I often wonder, “Should I be more afraid of a criminal who might rob me or of a uniformed officer who steals with a license?” Today, I suffer from post-traumatic stress as the result of my unfair arrest.

At night, I struggle to sleep. When I do doze off, I find myself immersed in a nightmare where I’m being shot at. I wake up agitated and sweating. Every time I hear a police siren, anxiety and fear flood my body. Having spoke about the incident publicly, I also fear retaliation.

The only positive takeaway is that on that day we got arrested, we were 33 strangers. Today, we are 33 friends bonded for life. Having lived through the same powerful ordeal, we created an environment of support and brotherhood among us. We help each other through the psychological toll, and with money or housing.

When I initially decided to testify, I saw it as a form of therapy. I needed closure from what happened to me. I never intended to become a community leader, but I feel grateful that my words touched so many people. Receiving so many words of support made me feel less alone.

For years, I witnessed people being deprived of their freedom, and did my best to fight for them. I saw the way authorities completely disregarded their rights and treated them like animals, but I never imagined it would happen to me. I hope, in time, the world will accept us for who we are. Until then, the fight will go on and we will stand strong.