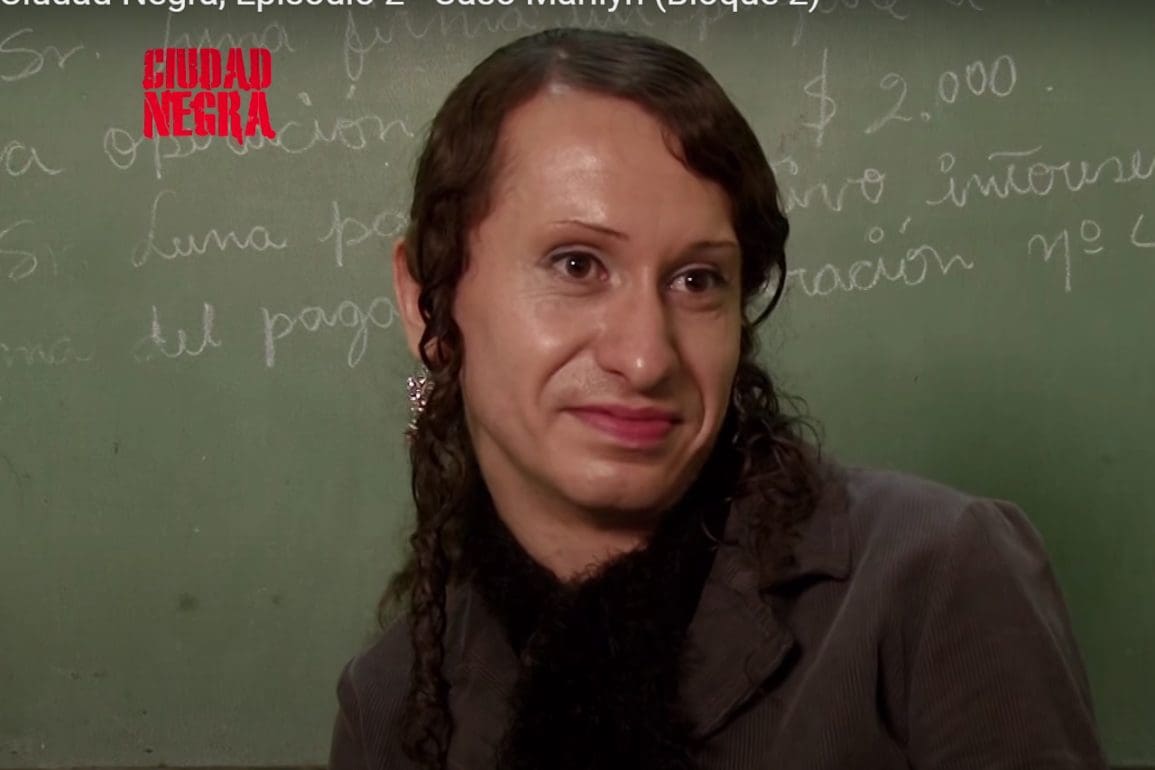

Schools in India ban hijabs, Muslim woman speaks out: “A piece of cloth should never determine whether a girl can study.”

When the home minister of India made statements in support of the ban on hijabs in schools it felt like a scar on all of us, who have already gone through so much.

- 2 years ago

March 22, 2024

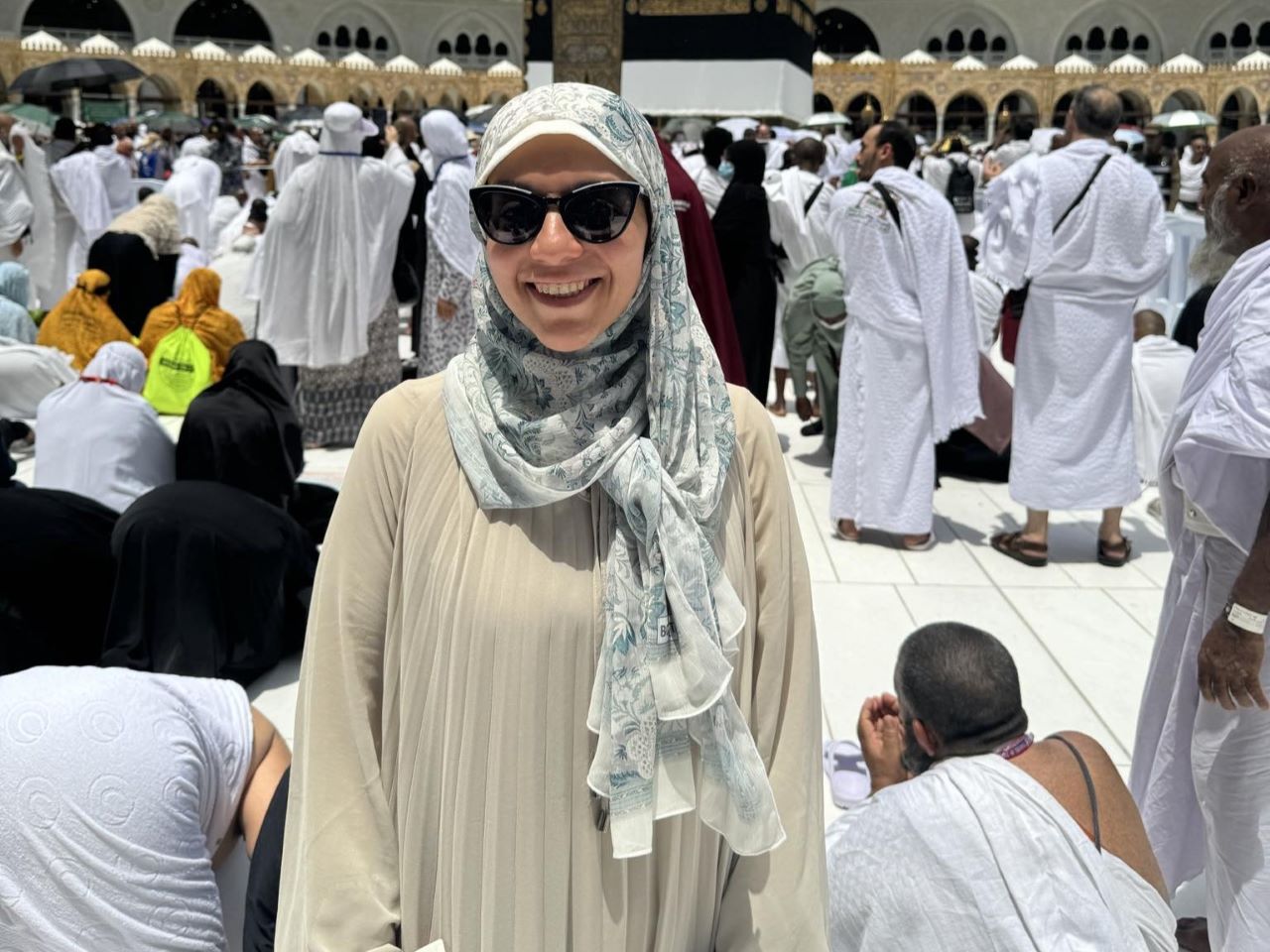

JAIPUR, India ꟷ I first wore a hijab (a head scarf) at seven years old, which my father brought one to me from Saudi Arabia. The brown cloth with an intricate sequence of gold looked beautiful and I fell in love with wearing it. Throughout school and into college, I wore scarves that matched my uniform. Yet, as time passed, I realized people around me felt uncomfortable with it.

During my early years at a Muslim-run school, all the girls wore hijabs, but college proved different. I watched as people scanned me with their eyes. Their gaze seemed to say, “You are uneducated and backward.” It took me some time to realize these people saw my headscarf as a sign of low status. Few accepted me with my hijab, and some even said, “If you removed the scarf you would look beautiful.” I never agreed.

Read more stories about women’s rights issues from around the globe at Orato World Media.

Wearing a hijab or burqa, some look at Muslim women like prisoners who need to be set free

Throughout college, people were curious about my headscarf. “Does the Quaran guide you to wear it,” they would ask. “And why don’t men wear one? Why are the rules different for men and women?” I often relayed the questions to my father, and he would say, “No man from the outside should see any part of a girl’s body.” I understood and followed, but I kept my own beliefs: the scarf was simply an extra piece of cloth I covered my head with until I married.

I understood, too, that when many women married, they would then don a burqa in public (a long, loose garment covering the entire body from head to feet). In my modern family, wearing a hijab felt like a choice. No one forced me. I simply liked it and felt motivated by what I read in our religious texts. Having choice mattered to me, though my mom often joked, “You only wear it because you don’t want to comb your hair!”

Only after coming to India, did I feel the social issues arise around my scarf. It never felt like that when I worked in places like Saudi Arabia or Dubai. In those places, I encountered friendly people and many Muslim women who did or did not wear Hijabs. No one bothered about it. The headscarf itself harms no one, and this is what I want the people of India to understand.

Last year I took a job at a top organization in my field in India. I suddenly saw how bias permeated even liberal circles. While most people acted nice, I encountered some who looked at me like a prisoner in chains who needed to be set free.

Muslim woman faces scrutiny for wearing a hijab at airport security

The problem really came to light for me when I began traveling for work. Passing through security checkpoints and immigration services at several international airports, the Indian immigration officers often gave me problems. In no other country had I faced extra time arguing or being held back. On one occasion in Hyderabad, a city in Southern India, a female security officer at the airport became adamant I remove my scarf.

I refused but offered to push it back to my hairline. She said no, so I proposed we go to a private room together to remove it. Again, she refused, and I felt the anger flowing through me. “Call your senior,” I demanded, upon which she let me go. Moments like this feel so embarrassing, and they annoy everyone standing in line. People look at me like a troublemaker, and I just want them to understand.

Things only worsened when I applied for a driver’s license. I passed the test, and everything went smoothly, but my license never arrived. When we inquired, the officer said, “You were wearing a burqa in your photo.” I felt surprised, because all my identity cards have similar photos, but the fight to get my license proved long and hard.

Today, I do wear a black burqa. I began to wear it after getting married. I love wearing a hijab but not the burqa. Yet, I can say, it was not forced upon me. I wear it as a choice to honor my religion and culture. Still, I maintain my own ideas. As far as the Quaran is concerned, it does not specify exact attire for women, only modest clothing. Rather, it instructs men to lower their gaze, which only makes sense if women are not shrouded from head to toe.

Home minister of India backs bans on hijabs in schools

Living in India, I experience a country of diverse religions and cultures. Muslims wear headscarves and burqas, but you also see Sikhs in the streets wearing turbans and carrying kirpans (small knives) as part of their religious identity. Yet, when I watch a Sikh go through a security line, I never see him being asked to remove his turban. This harassment centers mainly around Muslim women; surely no one would do it to a man.

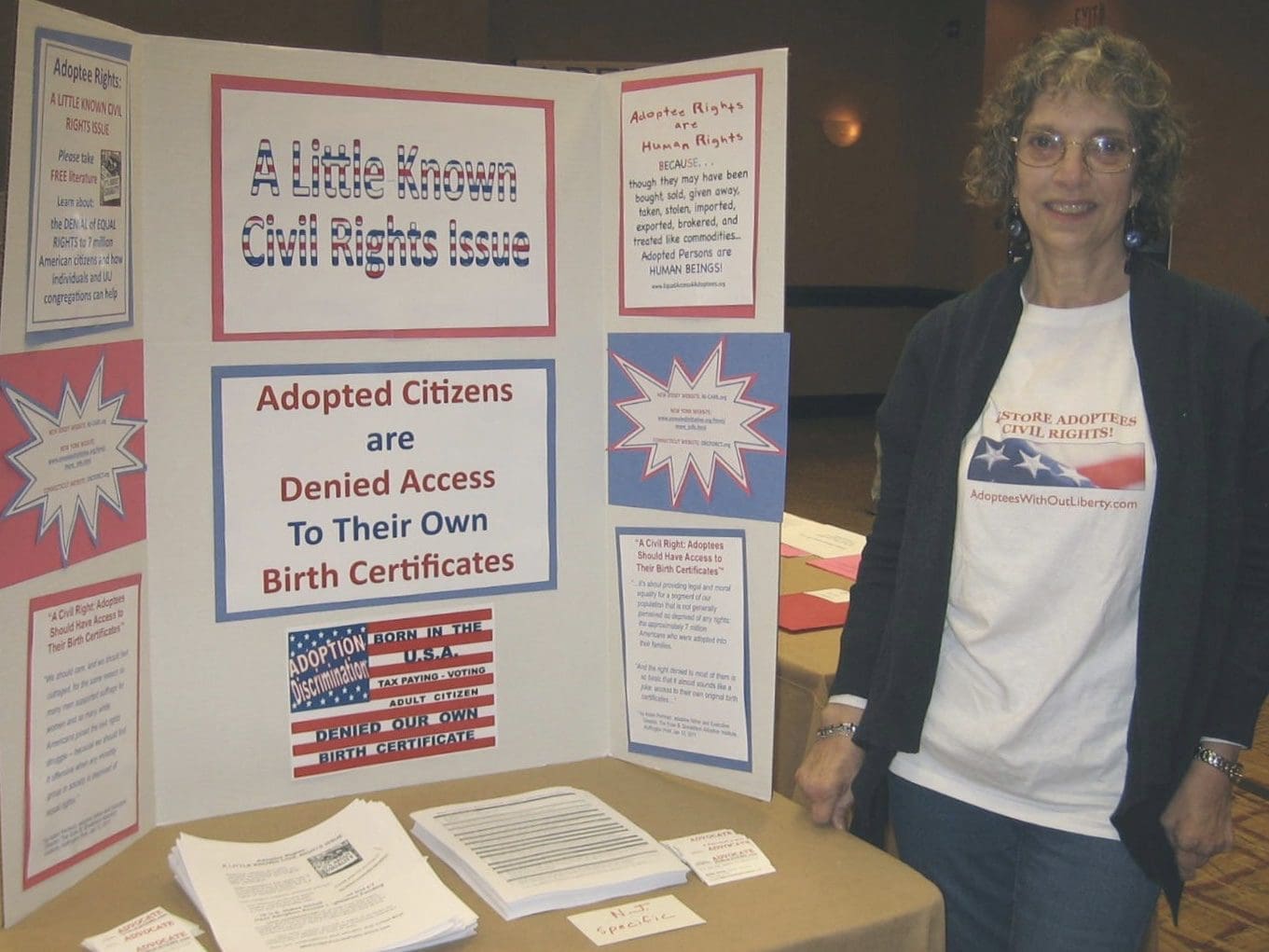

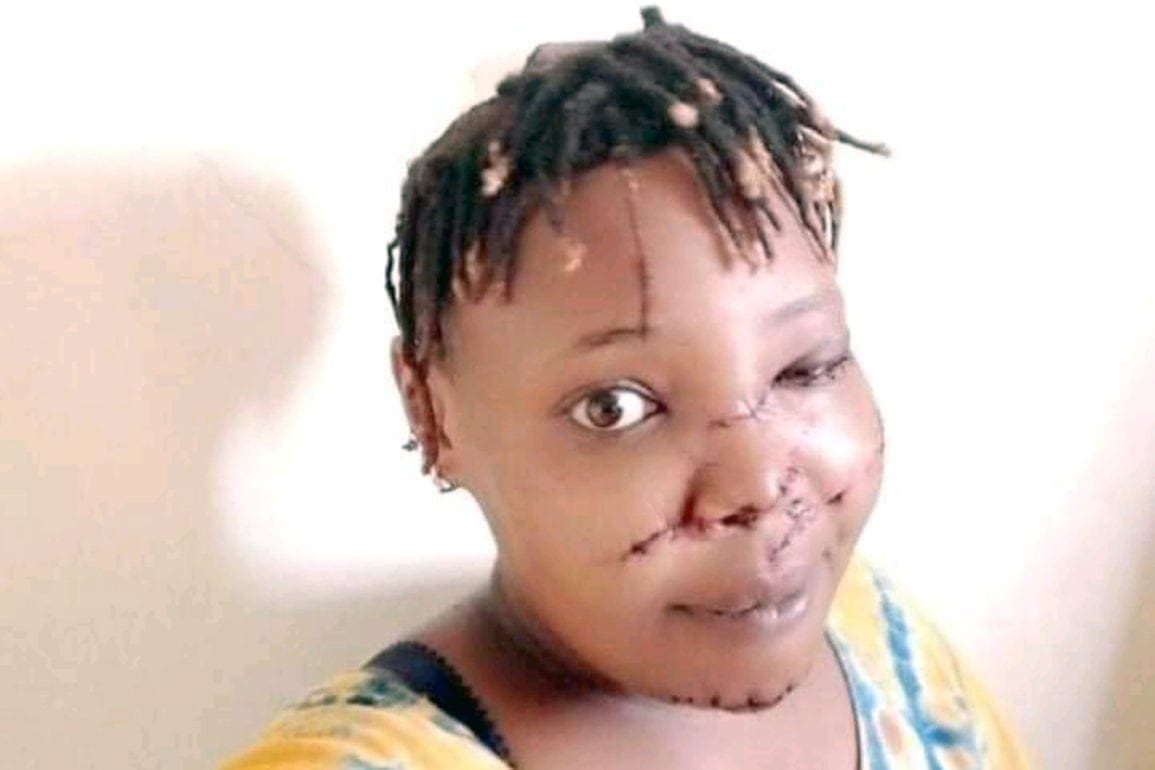

When the home minister of India made statements in support of the ban on hijabs in schools it felt like a scar on all of us, who have already gone through so much. [The home minister said “he favored students wearing uniforms in schools rather than any religious attire… Following this, the state of Karnataka imposed a ban, which sparked widespread Muslim protests, according to Reuters.]

In my own family, I watched as my aunt, who never wore a hijab, begin to wear one as a form of protest. Visiting Kashmir one day, I heard women repeating a popular slogan. “We cover our heads and not our brains,” they chanted. I felt their words and it influenced my own conviction. As more women donned hijabs to stand in unity, people accused us of trying to draw unnecessary attention.

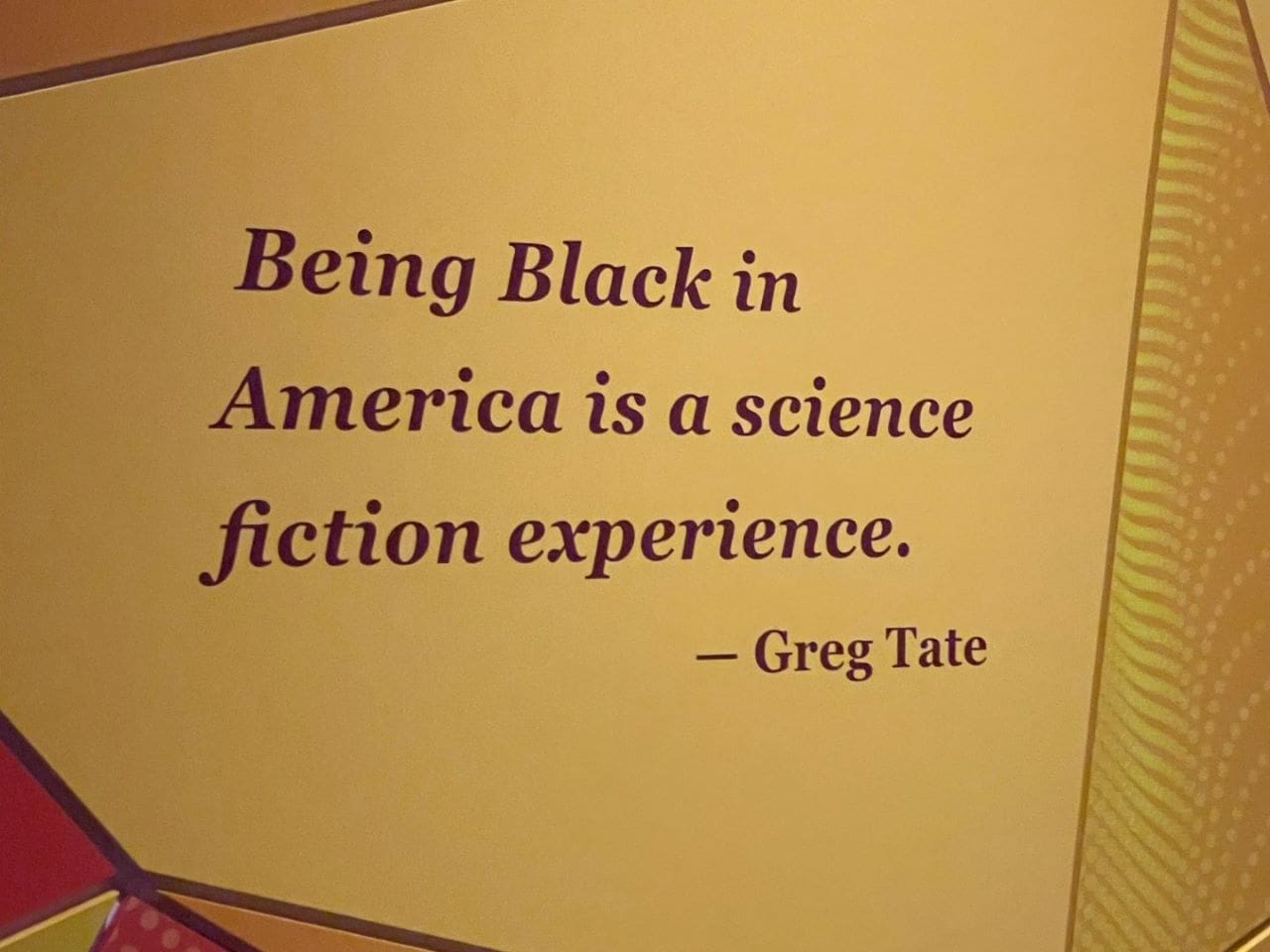

We now face controversies my parents never grappled with. Contrary to popular belief, many Muslim women wear hijabs and burqas by choice. I view it as a non-conflict. Wearing religious attire or following a religious belief, and the protests taking place in India, allow people in power to focus more on what women wear than the things in society that need real attention. A piece of cloth should never determine whether a girl can study.