Trans high school in Argentina enrolls adults, inspires singer to break through barriers

At 45 years old, I wake up in the morning and have breakfast. Checking that I have everything I need in my folder, I head off to school. I board the city busy from my neighborhood of Belgrano and travel to the city center. Going back to high school as an adult at La Mocha Cellis gave me wings.

- 4 years ago

July 3, 2022

BUENOS AIRES, Argentina ꟷ As a 45-year-old trans woman, I am about to graduate from La Mocha Cellis high school. La Mocha changed my outlook and offered me the opportunity to believe in myself again; to deconstruct who I thought I was and embrace my rights. They also inspired me to chase my dreams and I became the first trans person in over thirty years to sing at the national Chamamé Festival.

Family accepts transition, but educational system does not

I awoke to my gender identity at a young age and was lucky to have parents who accompanied me throughout the process. In the 1980’s society’s response to gender identity was generally disastrous, but my mother searched for better answers.

Born male at birth, the doctors soon found I had a higher-than-average percentage of female hormones, but they allowed and accepted it. No one tried to reverse my biology. They just let me be. With this essential support, I was permitted to construct my gender identity early.

I remember, at the age of 12, I sat down with my mother and told her I wanted to wear girl’s overalls and grow out my hair. My mother asked, “What do you want to be?” I said I wanted to be a girl and call myself Claudia; to lead the life of a woman.

With tears in her eyes, my mother explained it would be hard to accept because she did not want me to face a difficult life; she did not want me to suffer. In the eighties, many trans women were killed and subjected to prostitution. Yet, little by little, media characters like Cris Miró broke the stereotypes and showed us new possibilities.

While I had acceptance at home, school proved much harder. I entered secondary school but could not finish. They forced me to wear a male uniform and bullied me. Teachers failed me in courses on purpose because those at the table held homophobic and transphobic views. Although I complained and became very angry, I resigned myself to the situation. Leaving school at the age of 14 made me feel like a martyr.

I began working as an assistant at the radio station in my town, reading small messages on the air, and I fell in love with public speaking, journalism, and singing. I worked on several radio programs, and years later wrote articles. Yet, having left school so young, I saw no possibilities for my education.

COVID-19 rocks the transgender community, La Mocha extends support

Throughout adulthood, I threw in the towel on finishing high school or going to college and instead pursued music, but the road proved difficult. The industry rarely accepted transgender people and the musical style I enjoyed called Chamamé predominantly attracted cisgendered men.

Arriving on the electro-pop scene in Buenos Aires in 1999, everyone focused on the fact that I looked like a trans girl. I made my way to the underground and began exploring other genres of music. As the years passed, the ups and downs of life plagued me. I tried to be true to myself, but society kept me in the dark; it pretended I did not exist.

The arrival of the COVID-19 Pandemic in 2020 caused great suffering among the trans community. Those whose only source of income came from prostitution found they could no longer work. Great poverty and extreme necessity ensued, creating perilous situations for many people in our community.

My husband, who served as a teacher at that time, lost his job during COVID. With no work to be found, we faced the reality of having little food to eat. I learned from my friends about a group at La Mocha Cellis handing out food.

I encountered the director of La Mocha at the food distribution site, and he later contacted me to offer support. They began helping me with medical treatments, medications, food, and even invited me to finish high school. Just thinking about it overwhelms me with emotion.

La Mocha Cellis high school welcomes trans women

At 45 years old, I wake up in the morning and have breakfast. Checking that I have everything I need in my folder, I head off to school. I board the city bus from my neighborhood of Belgrano and travel to the city center.

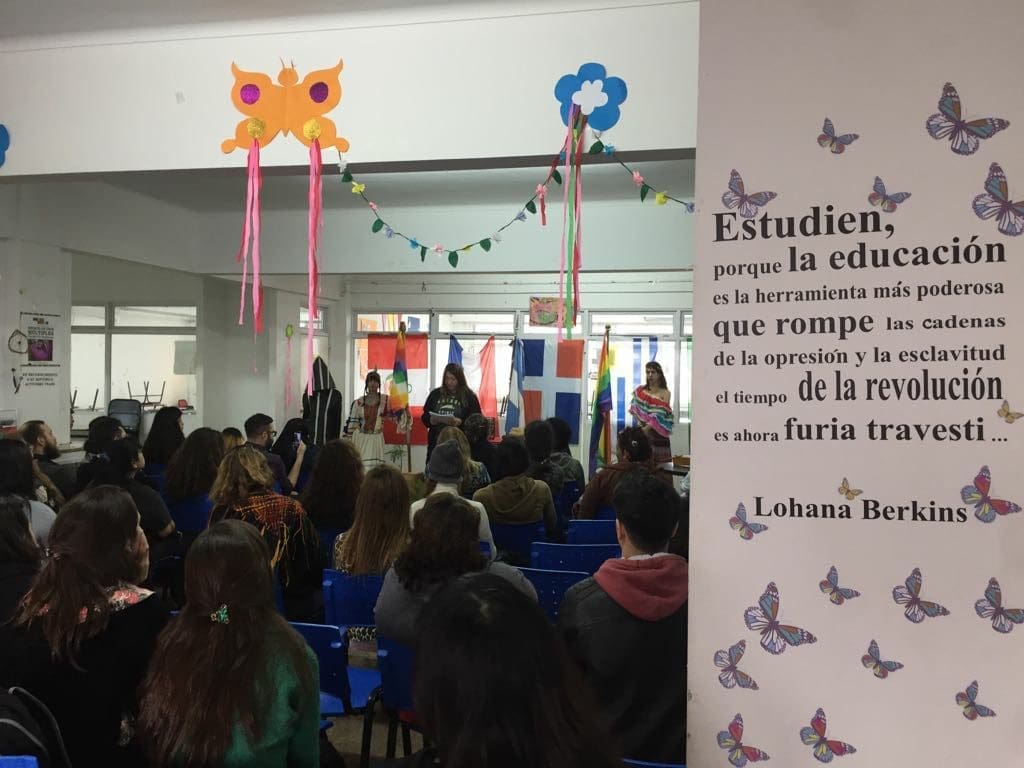

Going back to high school as an adult at La Mocha Cellis gave me wings. La Mocha became a reality 11 years ago following 30 years of trans militancy and activism in Argentina. Pioneers fought to guarantee people like me life, survival, and human rights. Today it stands as a school and a civil association conducting many important projects.

Transgender individuals serve as my teachers. I see transgender and non-binary people in leadership every day. Now I can recognize the importance of the things missing from my life before – things like human rights, gender and sexual diversity, and non-binary comprehensive sexual education.

In school, I encounter other populations too. To promote intersectionality, my classmates include migrants, single mothers, Afro-descendants, the vulnerable, and individuals from the slum Villero movement.

I used to wonder if I would be alive next week but today, after three years of studying, and with graduation looming, I dare to dream. For me, school is everything. This year, I will graduate knowing school is a luxury many trans women cannot access.

La Mocha taught me that education is a gateway to access other rights through the gender identity law sanctioned in 2012 in Argentina. Every day, as I attend La Mocha, satisfaction rises inside of me. I feel visible and free.

Trans woman chases her dream to sing on stage

Eventually, school officials discovered I could sing and proposed I put together a musical project integrating voices of different artists from throughout Argentina. We named the project “Unidos por la Música” or “United for Music.”

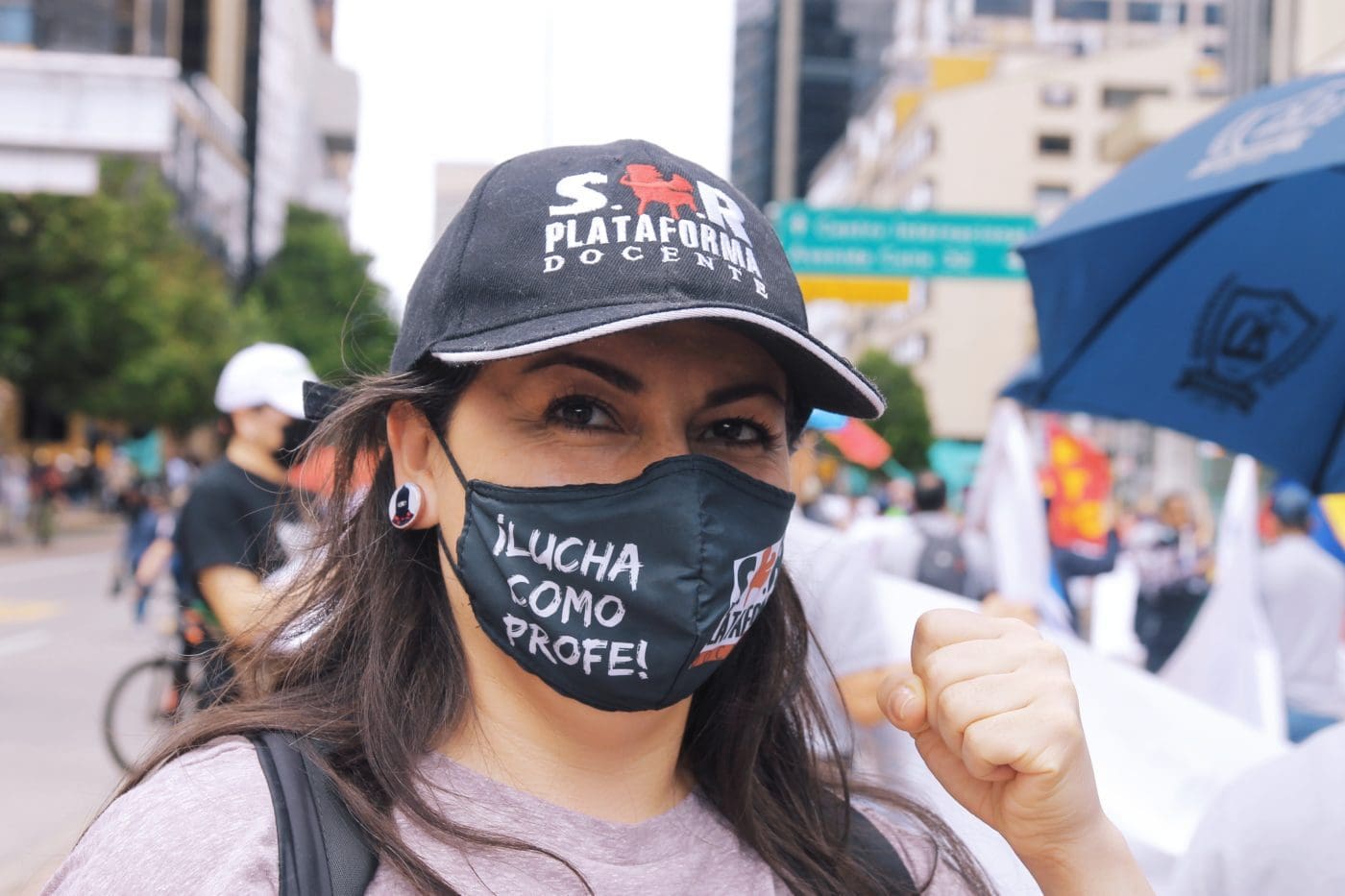

Our goal became to fight for trans rights through a law in existence giving women access to the stage. That law included trans women, but it rarely got enforced.

As the project launched, we faced resistance, obstacles, and lack of resources, but desire propelled us forward. At the 31st National Chamamé Festival, I became the first trans woman to sing on stage. With support from the Senate, cultural sectors, and several provinces, we made history.

When I walked out on stage, the announcer introduced me as a singer representing Corrientes where I grew up. They did not introduce me as a trans woman because there was no need to clarify my identity. I was simply a performer.

Everything in my life became possible thanks to La Mocha. They accompanied me through it all and I never felt neglected. My teachers encouraged me to remove the word “no” from my forehead. So many trans women never allow themselves to dream. Today, I push my own limits. I celebrate being alive. With pride, I stand tall as a trans woman knowing I can finally live free.

Envisioning a brighter future for all trans people in Argentina

When I consider what the future holds, I image continually growing, learning, and expanding my project United for Music. I want to oversee performances in the provinces, to offer trans artists greater support and access to the arts, and to continue accessing the stage at popular festivals.

I envision singing with people I admired when I was a little girl and continuing my studies in speech and journalism. Even more so, I want to stay involved at La Mocha Cellis; to give back the way people did for me.

Consider for a moment that the life expectancy of a trans person in Argentina is only 40 years old. Very few of us reach the age of 60. This is a world where we are systematically criminalized, pathologized, and discriminated against. It starts early. The first thing a trans person is often denied is love. Many of us lacked love of family, love in school, and love from society. Trans people continue to be murdered in the streets.

La Mocha Cellis saves lives. It rescues those who face mistreatment, destruction, and ferocious carnage; whose souls become empty. The volunteers and donors made it happen, going into “red zones” early on to talk to trans people. Today, the school has hosted more than 300 students.

More than a high school, La Mocha offers a public library, shelter care network, psychological support, doctors, lawyers, social workers, and advocacy. They lead all of Latin America in rethinking the critical stance toward pedagogy and a non-binary world view.

This place that changed my life has become a school full of tenderness, which validates our voices, creates a collective of trans people, and legitimizes us. We exist and La Mocha is the pure love trans women need.