Former political prisoner fights to preserve Albanian cultural heritage

The mine was an unimaginable situation; the hammers and explosions created unbearable amounts of dust, all of which you breathed in. There was no water. When you came out, black dust coated you completely.

- 4 years ago

May 30, 2022

TIRANA, Albania—I spent 17 years in prison for allegedly being an enemy of my country during the totalitarian, Stalinist-style communist rule of Envar Hoxha. I endured the worst years of my life behind those walls. Now, I walk around Tirana and see how the new governments are trying to erase our history. It’s terrible.

Authoritarian Hoxha regime targets enemies of all types

Hoxha clung to the extreme ideologies of the Soviet Union’s Joseph Stalin, long past his successor Nikita Khrushchev condemning them. If Hoxha’s government accused you of a crime, you were classified as an enemy of the working class, which turned you into an enemy of the party and the socialist state in general. It repressed the entire population.

The regime’s campaign against its political enemies began in the 1970s in three different purges. The first was ideological, which resulted in the repression of intellectuals and artists. This is when they imprisoned my father and accused him of being a “liberal,” or person who wanted to open the door to the degenerative influence of the West.

The second purge affected the military, and the third involved those accused of sabotage. The government arrested and sentenced according to various articles of the Penal Code, the most common being “Agitation and Propaganda against the Regime.” Sentences ranged from three to ten years in prison.

However, the worst punishment, death, was for those who tried to flee the country, an action the Penal Code considered “Treason.”

I receive prison sentences, my friends face death

The first time the regime imprisoned me, it was for agitation and propaganda was when they found my diaries and writings with my thoughts against Hoxha. They sent me to the Burrel prison where I was to spend seven years.

The second sentence came while I was serving the first. A group of imprisoned intellectuals, including two journalist friends of mine, sent a letter speaking out against Hoxha. The government sentenced them to death for “Creation of a Counterrevolutionary Organization.”

They declared me a member of this alleged organization because of my ties to the journalists. After a sham of an investigative process without even the right to appeal, they sentenced me to another 16 years in prison.

For the crime of writing a letter, my friends were executed.

Locked up in the worst gulag in Stalinist Albania

With the second sentence came my transfer to Spaç. They sent me there as my father was in Burrel Prison, and they didn’t want families to be together.

Spaç was not just a prison; it also functioned as a labor camp where prisoners worked in mines in terrible conditions. If we didn’t comply, isolation cells awaited.

At Spaç, I didn’t have a single day off. Every day, they woke us at 5 in the morning, organized us into brigades, and took us to the mines where we worked all day. We did eight hours of work plus an hour and a half of transport each way to get to the mine.

The mine was an unimaginable situation; the hammers and explosions created unbearable amounts of dust, all of which you breathed in. There was no water. When you came out, black dust coated you completely.

My time in Spaç was a time of terror; I couldn’t feel safe even in my cell as we were more than 10 prisoners crammed into each one. They recruited prisoners as spies—they usually accepted as a means of survival and to avoid further punishments.

There came a time when I couldn’t take it anymore. It was clear to me that I was going to die there; I thought it impossible to survive 16 years like this. I refused to work.

And then the worst began—they sent me to the isolation cells.

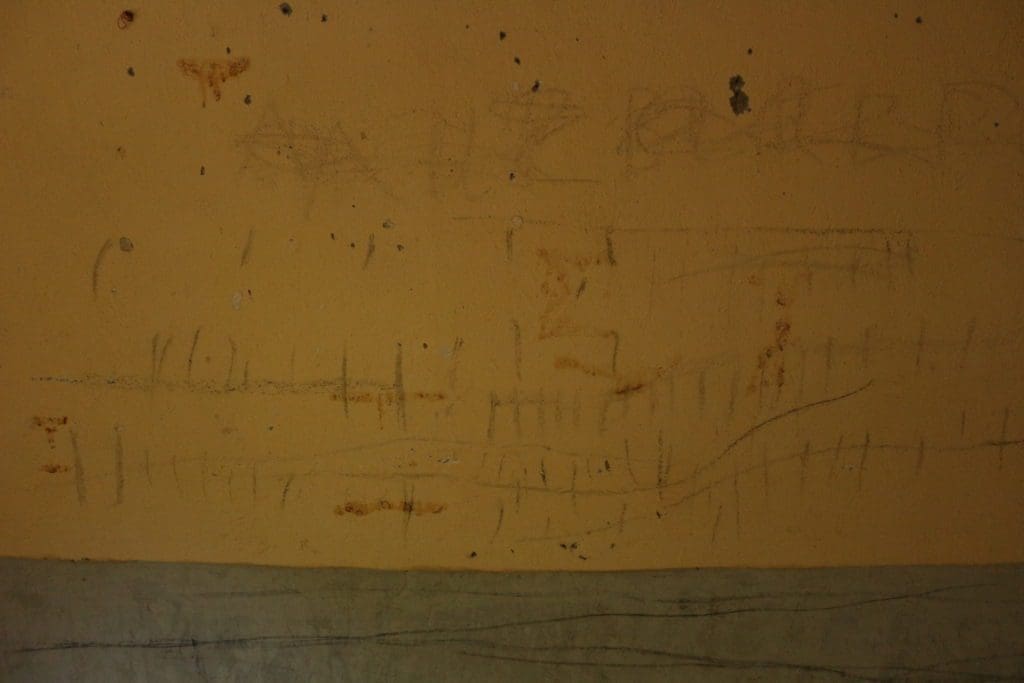

In these, time did not pass. I could never leave the cell; constantly alone, I was locked in those four walls without being able to contact anyone, without anything to do or occupy my mind. I remember scratching the walls and counting the days I had been in there.

The winter was especially bleak. I only had a sheet to cover myself. I was there for months, assuming every day that I was going to die in that cell.

The beginning of the end of my nightmare

Hoxha died while I was still imprisoned, and finally, the days of his regime were numbered.

They started to release some of the remaining 2,000 prisoners, but even then I was not freed, only taken back to Burel with a very small group of fellow “dangerous enemies.”

Following Albania’s first democratic elections in 1991, the Italian Prime Minister accused the government of continuing to hold political prisoners. As a result, I finally saw freedom again on March 17, 1991 after a total of 17 years in prison.

Fighting to preserve Albania’s past and cultural heritage

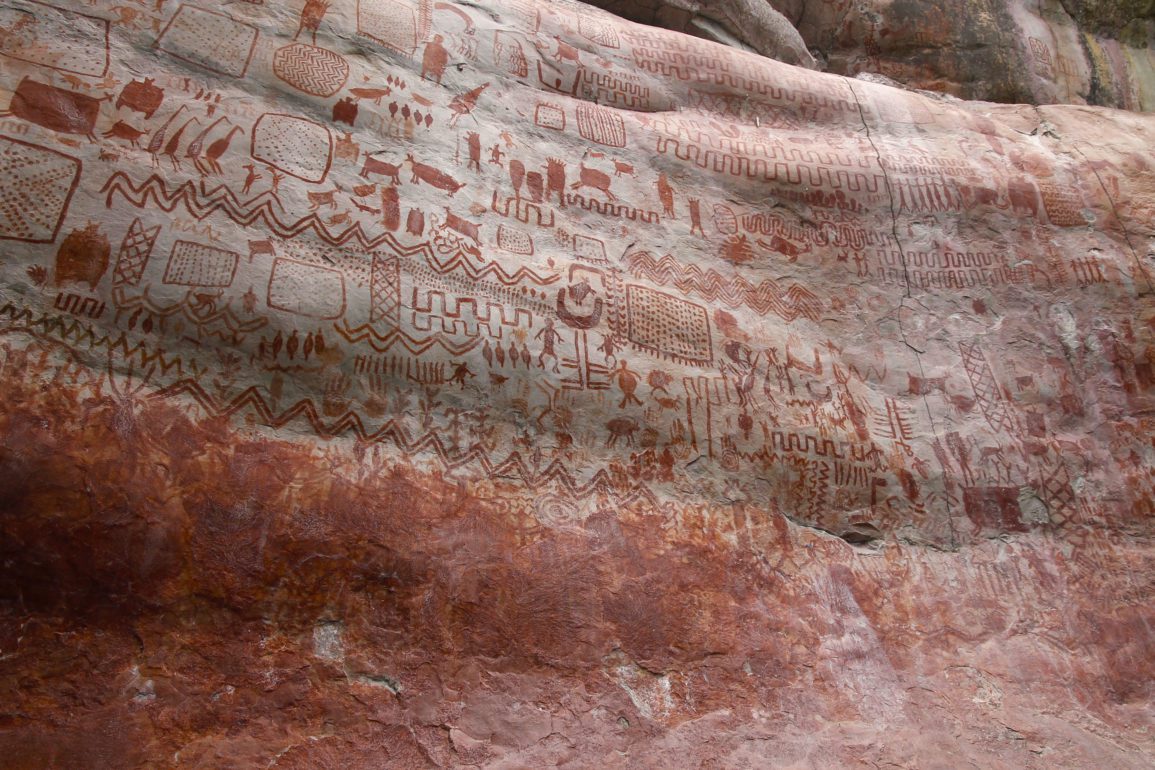

It has been more than 30 years since the Hoxha regime fell. Rather than preserving our history to learn from it, the government seems determined to see it obscured instead. This is a consequence of the years after the fall of communism when the elites in power had no interest in maintaining our Albanian cultural heritage.

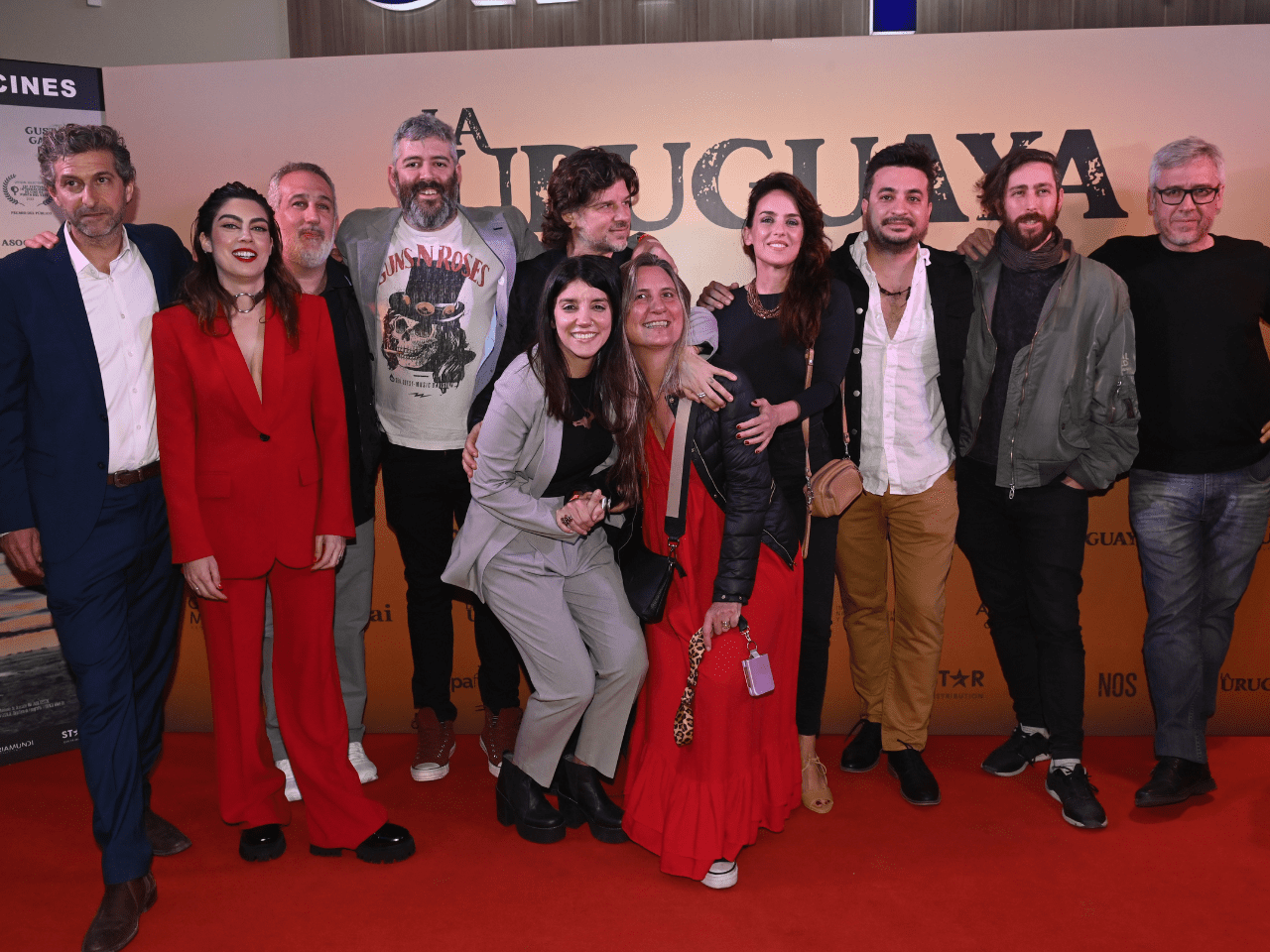

The Pyramid of Hoxha, formerly a museum of the Hoxha regime, is slated to convert to a kind of IT educational center for youth. The National Theater of Tirana has been destroyed.

Spaç is part of our history as well, and is practically in ruins. A foreign organization is in charge of keeping it standing, but members of the public can no longer see what I believe are the most important things, such as the mine or the view of the entire compound with its fences and control towers surrounded by mountains.

The government sees these places, like Spaç or the National Theater like trees to cut down for a profit. Many of our historical buildings that show our heritage those of the Ottoman Empire, those of Italian aesthetics, and even those of the Hoxha era—are gone in the name of new, large, modern buildings. I consider this a caricature of neoliberalism and globalization; it happens all over the world, but in countries like Albania, it is much more extreme.

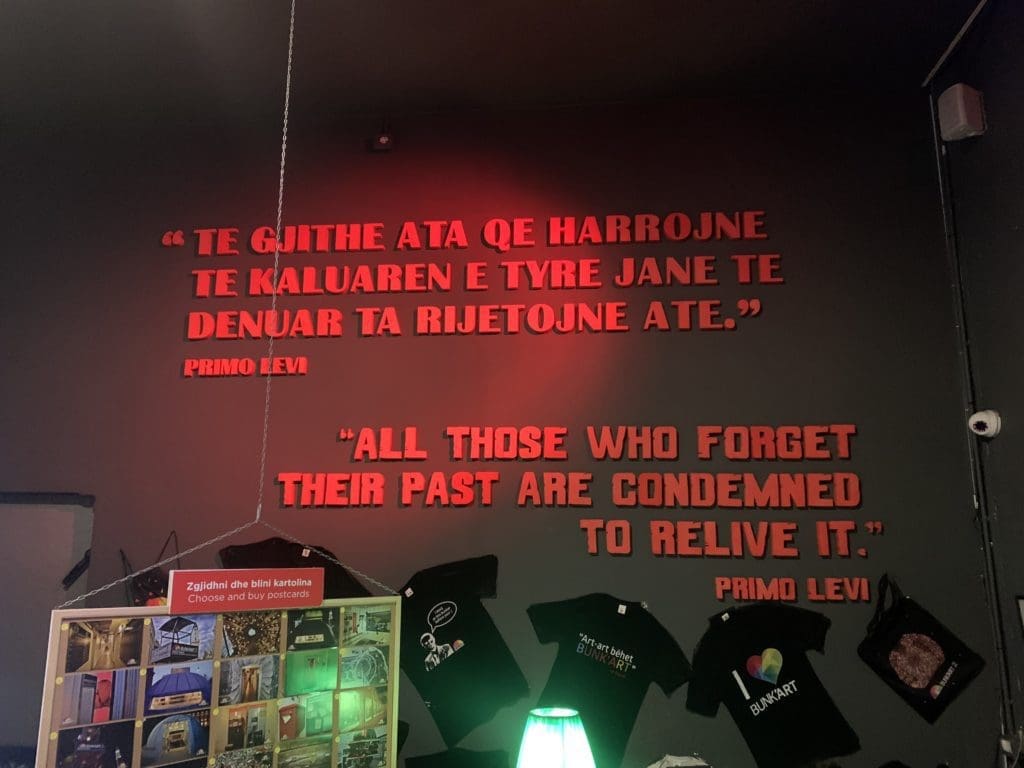

The destruction of these buildings continues our collective trauma, the kind experienced when someone dies at the hands of a regime: when one of us is killed, we are all killed. “Whoever forgets their history is doomed to repeat it”, said Primo Levi. In Albania, we cannot afford to forget places like Spaç, which have marked the soul of its people forever.

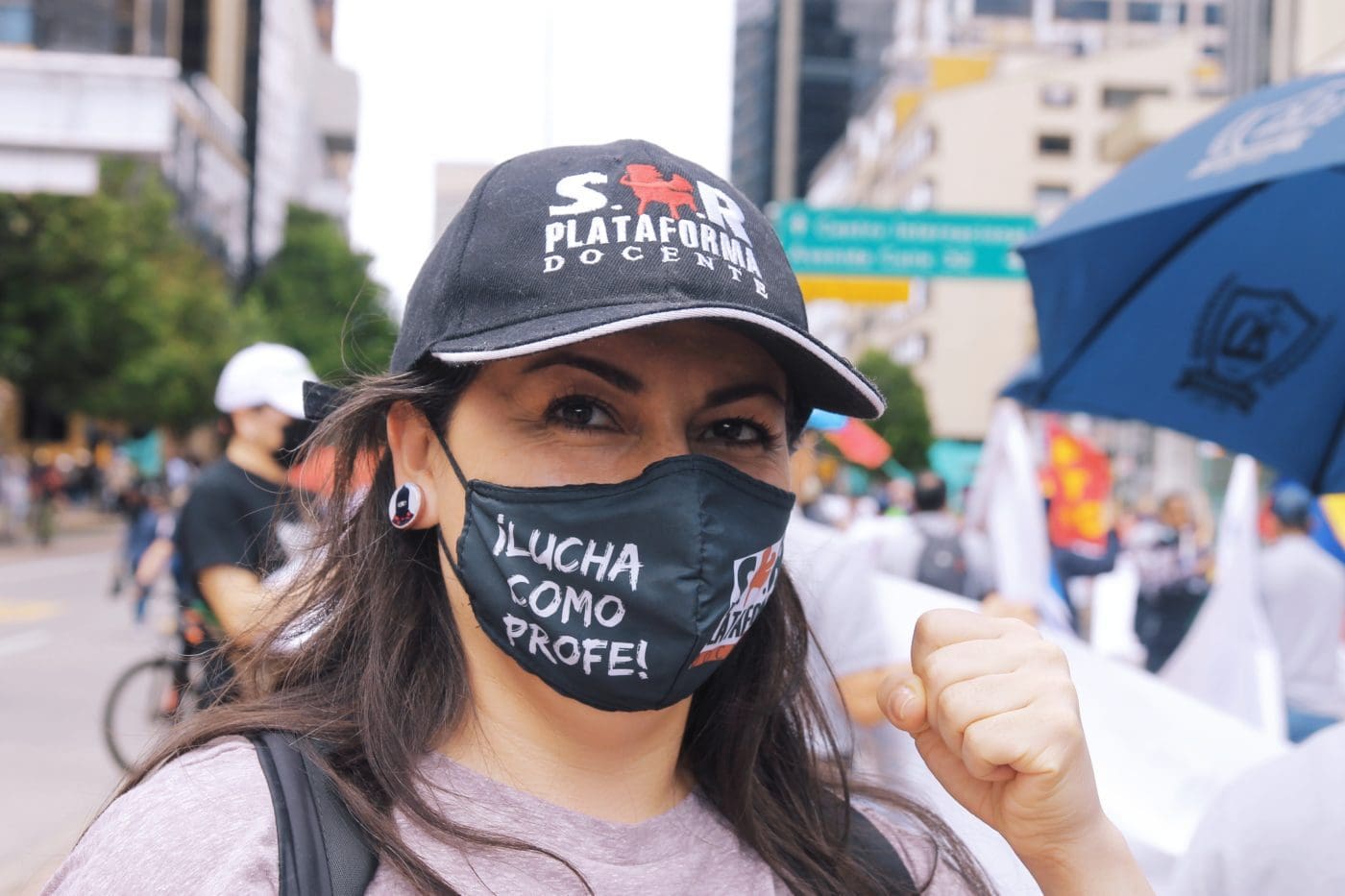

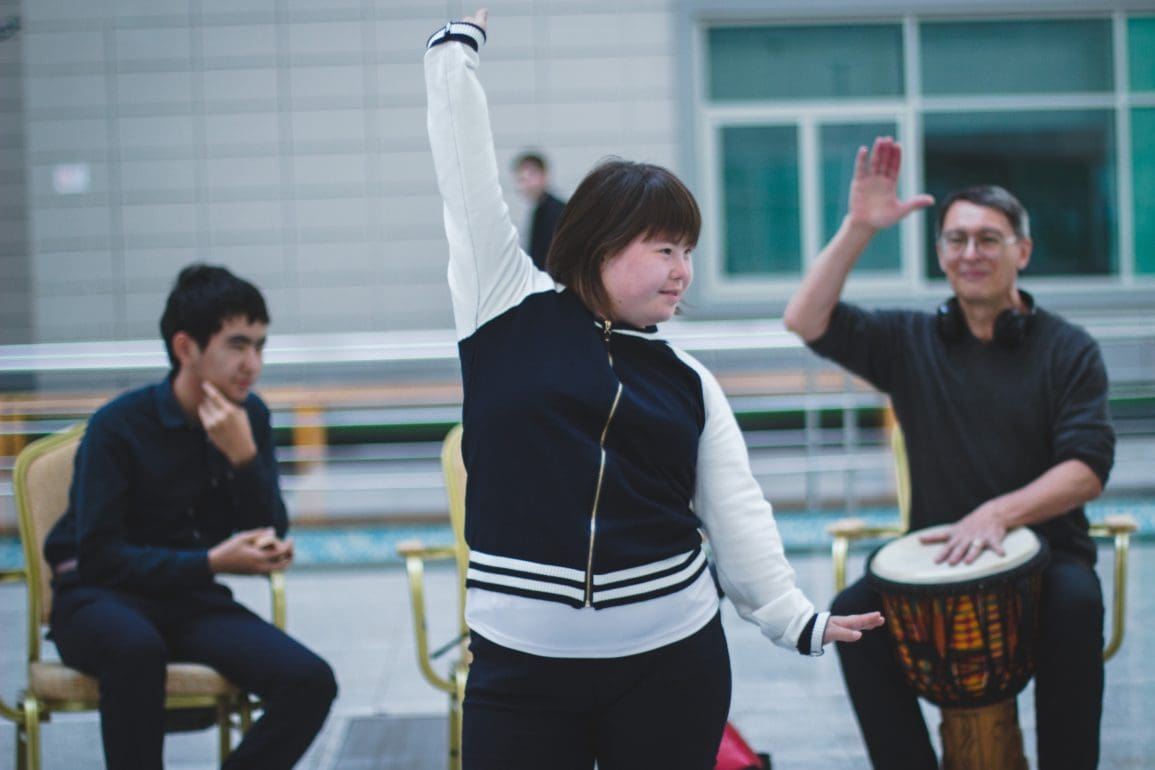

All photos by Marta Moreno Guerrero, except when otherwise noted