Wichi woman becomes first doctor from her indigenous community, seeks to blend science with ancient, ancestral beliefs

I tell younger members of the Wichi community, “We are the ones who must stand up to defend our rights. We may be accustomed to others doing it for us, but now we have resources and abilities. We get to decide for ourselves.”

- 2 years ago

February 7, 2024

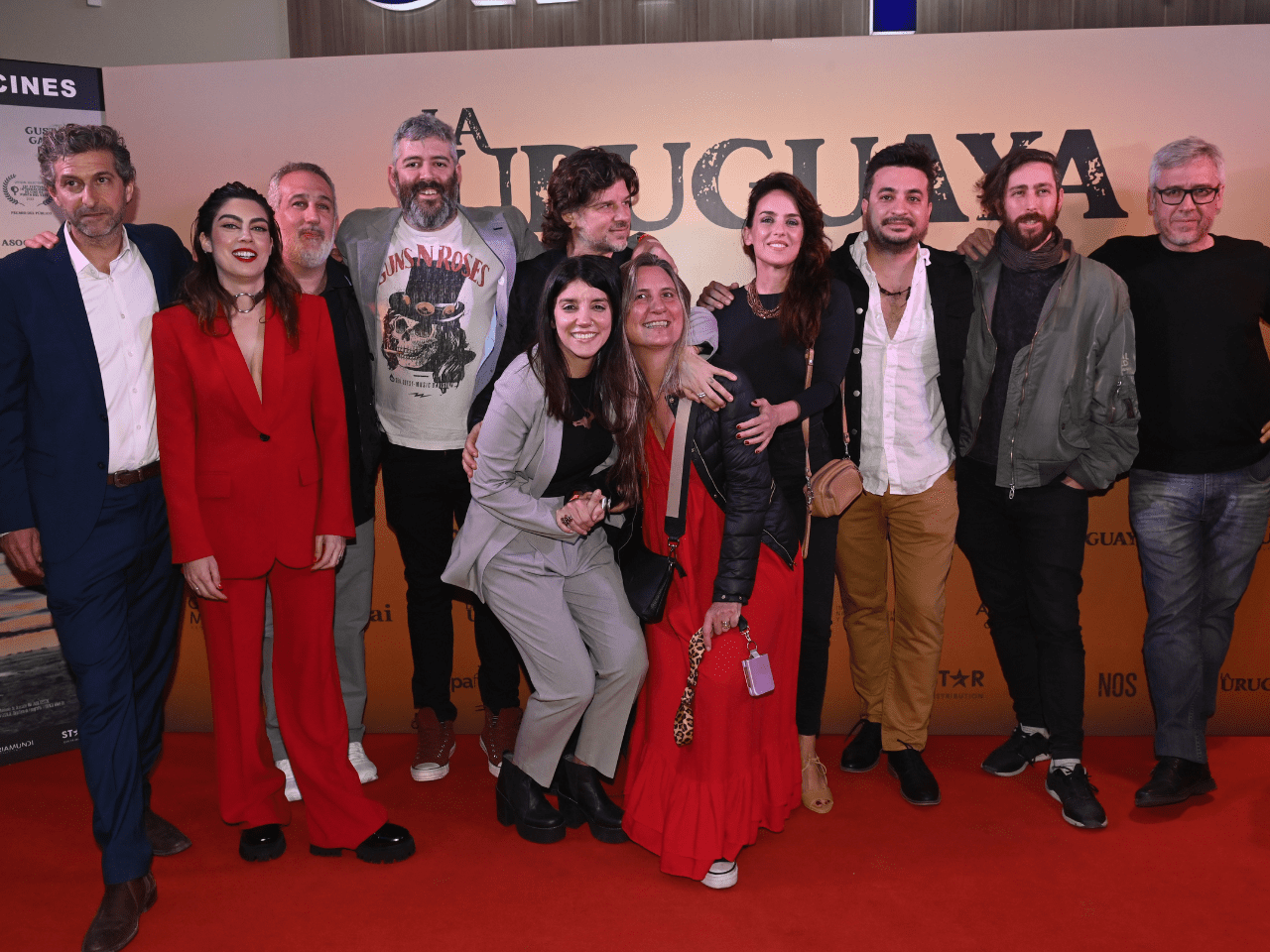

INGENIERO JUAREZ, Formosa, Argentina ꟷ As an indigenous person from the Wichi tribe, becoming the first doctor from my community fills me with pride and excitement. The big day arrived on December 15, 2023. I entered the classroom to take my last test holding the Whipala flag.

When I passed, a great emotion surged through me, accompanied by an indescribable energy. Between tears and laughter, I walked quickly to the door, expecting to find myself alone with my loved ones. Instead, I saw a crowd of thousands of people. I stood there, in front of my parents, siblings, classmates, teachers, administrators, and journalists, crying and smiling.

When I raised the Whipala flag high above my head, the people began to clap and shout. I hugged my parents and siblings for a long while and felt the presence of my ancestors. They were with me every step of the way. By raising the flag, I defied the brutality we faced for centuries; I dared to dream.

Read more indigenous stories from around the globe at Orato World Media.

Fleeing from the harsh lands the Wichi people were driven into, my parents offered me an opportunity

Until the beginning of the last century, the Wichi people inhabited millions of hectares of native forest, but slowly we were confined to a fraction of that area. My old and ancestral community includes about 20,000 Wichi people today.

As companies came in for agricultural expansion, they devastated our forests and violently drove us out. We found ourselves in harsh lands, isolated and without electricity or drinking water. Thanks to my people’s ancient knowledge, they knew how to use the abundance of nature around them without preying on it.

They also knew how to survive harsh climatic events like long periods of drought in winter, and soaring temperatures and torrential rain in summer. Faced with these circumstances, my parents decided to make a change. They left the lands where my grandparents lived in search of better opportunities. They wanted to fight for our culture using other tools.

There, in Ingeniero Juárez – a small town in the province of Formosa – my parents taught my brothers and I the importance of education. They told us that learning was a form of defense for our people and culture. In my bilingual school – half Wichi and half Creole or white – my love of knowledge became everything to me. At home, we only spoke Wichi, and a strength grew inside of me; a desire to defend my people.

While I had not yet settled on an area of study, I knew deficiencies existed in health and education in the Wichi community. It felt like a form of injustice, and I wanted to change that. With the seed planted, a dream formed – to do something good for my people.

Every summer we made our way back to our people deep in the desert

Every summer, we left our home in Igeniero Juárez to visit my grandparents. We traveled by car across hard roads made of dirt and gravel, kicking up dust for nearly five hours. From time to time, the dry landscape briefly revealed a small lake, carob trees, and cattle. Iguanas lay in the scorching heat that overwhelmed me, as if the landscape itself was melting.

When it rained, those precarious roads became impassable, forcing us to turn around and wait. When we finally approached the community, small, constructed homes dotted the area. As nomadic people, the Wichi rarely stayed in one place for long, so they gave little importance to housing. The small and vulnerable structures are made today with the same dimensions and characteristics used by our ancestors.

On those summer mornings, my grandfather worked the land while my grandmother made handicrafts, preparing and weaving threads from Chaguar leaves. In our culture, we believe women descended from the sky using a long rope made of the same fiber. Those leaves carry great meaning.

In that place where my grandparents fled as young adults, consumed by pain and sadness, they let go of everything, even members of their own families. They learned to work with the arid, inhospitable, and hard land. They searched for water, fruit, and animals, enriching their community little by little. Like a twin with nature, they took advantage of what it offered them and they succeeded.

Then and now, the land speaks to us and we understand it. As Creoles strip the desert of everything, leaving it barren, my grandfather often asks, “What about us?”

Under a canopy of stars, I connected with my Wichi ancestry

In the afternoons in my grandparents’ community, as the sun set and the work hours dwindled, we gathered in a circle to talk. People often told traditional Wichi stories, passed down from generation to generation. One such story was that of Tocuaj, a hero of our civilization.

The stories began with Tocuaj’s teachings and as a girl, I felt immersed in the magic of the tale. In some stories, Tocuaj took human form but when he died, he resurrected. In others, he appeared as an animal, embarking on great adventures and teaching the people to hunt, fish, and farm. He also showed us the evils of man.

Listening to my grandfather speak of the origins of rain, thunder, and lightening, we passed the mate from hand to hand and laughed. Surrounded by love, peace settled over us as we ate meals made of corn, pumpkin, and chañar, generously provided by Mother Earth.

As night settled in, the sounds of nocturnal birds filled the air. The ground underneath my feet represented the land of the dead and the stars above were my ancestors in living form. Beside me, my grandmother wore her skirt made of colorful fabric and a shirt embroidered with flowers. Some ladies wore a small veil covering their hair symbolizing protection.

A people of few words – never violent and never in a hurry – we remained calm and timid by nature. Through conquest and marginalization, my people began to devalue our own consciousness, developing an attitude of submission and distrust toward the white man.

Wichi doctor urges young members of the community to fight for their rights

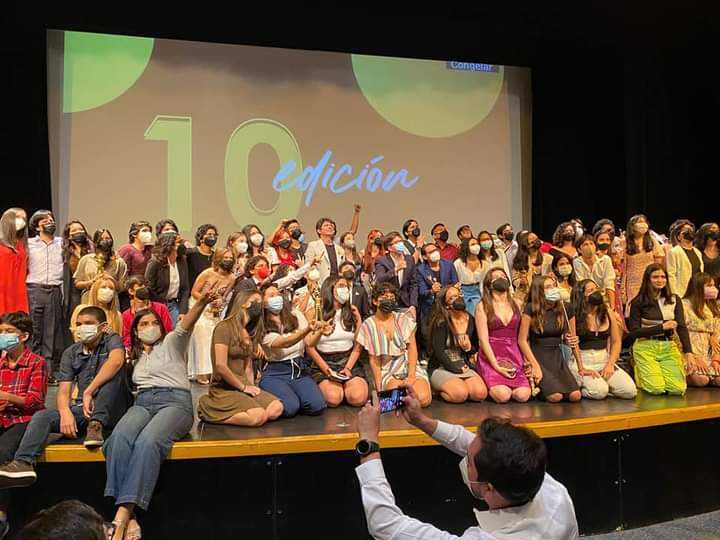

In support of my dream to go to college, my parents eventually moved me from my bilingual school to an all-white secondary school with higher academic standards. Shy and submissive, I rarely spoke. I had to learn Spanish, dress, and style my hair differently. I questioned walking between these two worlds, but I adapted, and it became a significant learning experience.

Despite adjusting to this new environment, I never sold out who I was and when I decided to pursue medicine, I became intent on helping my people. Moving to Corrientes for college proved to be another major transition. At moments, I felt dejected. In all the years at college, I never encountered another Wichi. Many of my people shied away from the distance and cultural risk of going to school. We all heard the stories of discrimination and unfairness in society. My people suffered so much already.

Through it all, I leaned on the unconditional support of my family. “Even if you fail, you move forward,” my father told me. “That is how you get to the goal.” Earning my degree and connecting my love of medicine and research with the needs of my community felt like fulfilling the wishes of my ancestors.

After my rotations in Corrientes, I plan to return to my people; to collaborate for the health of my community. For indigenous people, we face barriers to education and while leaders fight for aboriginals and rights exist, we often do not exercise them. As more and more of us become interested in education, we will see a shift.

Now, I tell younger members of the Wichi community, “We are the ones who must stand up to defend our rights. We may be accustomed to others doing it for us, but now we have resources and abilities. We get to decide for ourselves.”

Blending science and the beautiful ancestral beliefs of the Wichi, doctor may become the translator between two worlds

When it comes to the health of the Wichi communities, I see a great demand. The systems fail them, and work must be done. I propose a dialogue between our two worlds, to generate understanding of Wichi medicine.

Indigenous people see health not simply as a physical problem, but rather a plethora of factors that go beyond the human body. I aspire to integrate the ancestral and spiritual perspective of the Wichi people into medicine, thus changing the paradigm. Research will be key in this pursuit.

To me, science is beautiful. It cares for humans and seeks to understand the place where we live. At the same time, the wise worldview of my people vibrates in unity with nature. In our language, Wichi means human and my challenge in life is to rescue and preserve our value.

With nature as our primary giver, the one that nourishes and satisfies all of our needs, she is protected by the gods of living beings. These same gods – the lord of the fish, the owner of the mountains, the father of the birds – also punish us when we waste or overproduce. I look forward to bringing this view to a broader audience, while helping my beautiful community to thrive.