Blind gamer crushed the competition, became international sensation: now Rattlehead helps develop tech for visually impaired

Learning to play video games blind opened a parallel universe for me. I learned to walk in this new world, unafraid of the shadows. Each sound generated an indescribable light and warmth inside me.

- 2 years ago

February 17, 2024

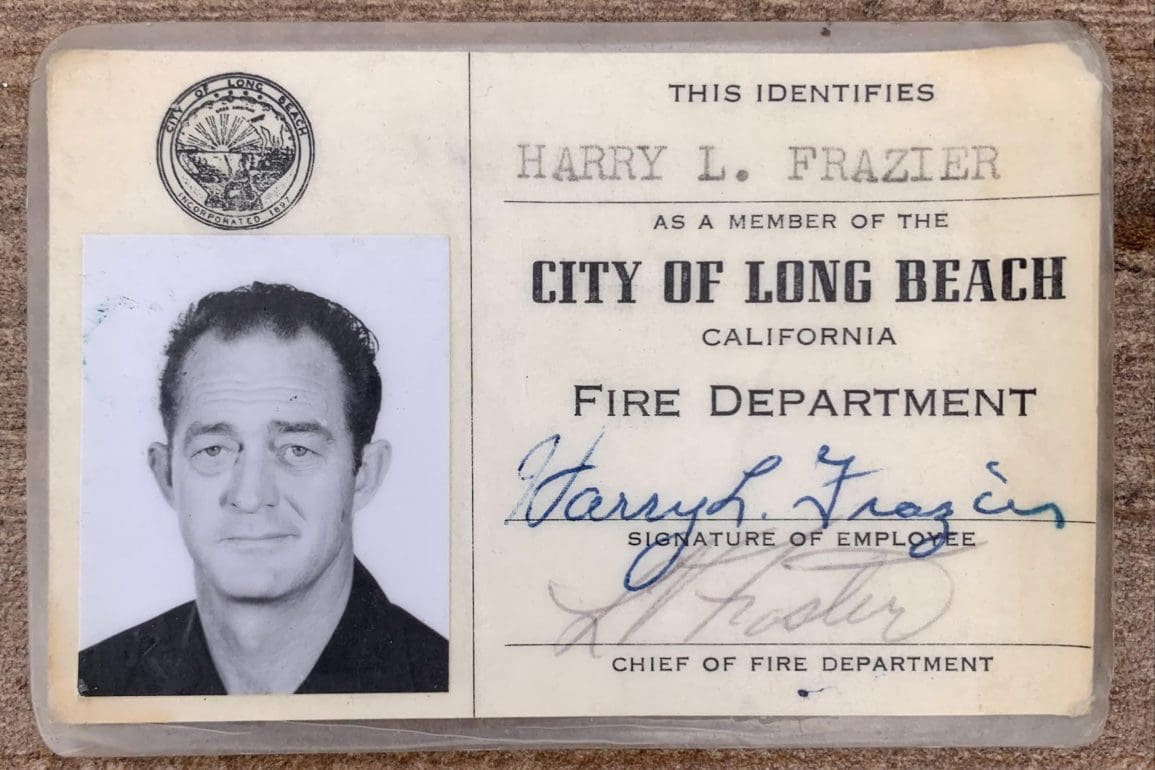

TEXAS, United States ꟷ In 1992, at six years old, I became a video game fanatic, escaping to the video game room after school for hours at a time. I think I learned to play games before reading and writing. On my tiptoes, with pockets full of coins, I leaned into the consoles, soon positioning myself as one of the best players there. Other gamers watched me excitedly. Soon I got my own gaming systems and lived the life of any boy my age. In my quiet neighborhood, I played soccer and video games.

Then, at the age of 11, I heard the worst news possible. During a consultation with doctors, they diagnosed me with a form of glaucoma – an eye condition that would take my sight little by little. When the doctors spoke the words, I heard my mother sobbing. With no cure, we faced a long, hard battle but I refused to change my habits, continuing with soccer and video games.

Going completely blind didn’t happen overnight

As images became blurry and I strained to see, we realized Guatemala had little to offer me to face my new condition, so we moved to the United States in search of more opportunities. For the first few years, I saw outlines of objects, but they lacked full details. As my vision grew worse and worse, it felt like a countdown. By the time I reached 24 years old, I went completely blind.

While my surroundings did not go black, they became grey – changing shades like a layer between the world and me. It felt like walking through the clouds. I missed seeing but I made my way to a new place mentally. This did not need to be an end, but rather a new beginning.

During my transition into being blind, I got a good education in the U.S. I learned to walk in the streets with a cane and use my ears to listen for traffic. I refused to spend the rest of my life alone, locked up in the house without friends. By the time I graduated from high school and went on to college, I felt independent and capable.

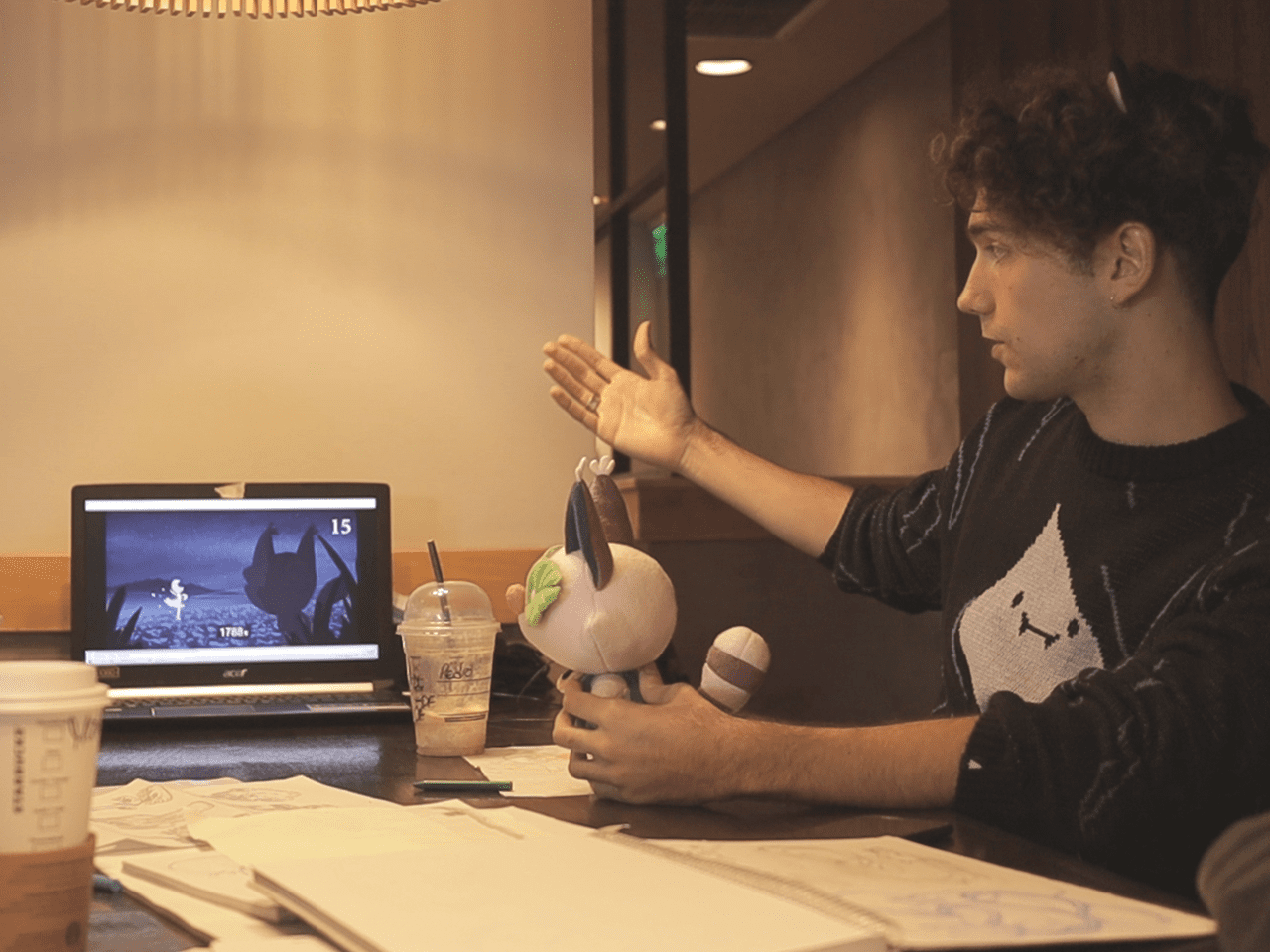

As I continued playing video games while my vision faded, I awakened to my other senses. Suddenly, I discovered a world of sound, creating a map by which I could travel. At home, sitting in the front of the computer, I found myself capable of identifying everything happening on screen. While mainstream games at that time lacked features for visually impaired people, I trained hard to learn every sound. I dedicated myself to distinguishing the sounds of each fighter’s movements, reacting to attacks in milliseconds.

Similar story: Inspired by Mortal Kombat metalsmith in Colombia makes dragons, designs for the stars

From Mortal Kombat, to winning international tournaments as Rattlehead, the industry turns toward accessibility

Learning to play video games blind opened a parallel universe for me. I learned to walk in this new world, unafraid of the shadows. Each sound generated an indescribable light and warmth inside me.

At 20 years old, I started playing Mortal Kombat. The game remained fairly inaccessible to blind people, but the sound engineers created a rich atmosphere in each scene, allowing me to “read” the game. With my new methods of listening, I loved Mortal Kombat, and never put it down.

Over the years, I realized sound contains certain characteristics that allow you to see without seeing. For example, fighters sound different on the left side than the right. Depending where a character is on screen, their special moves or powers take on slightly different tones. In time, I naturalized that richness and began appreciating it. Being one of the first to achieve this gave me total satisfaction. Soon, technologies like surround sound and vibration became even greater allies. I found myself able to appreciate details of video games people with sight tend to overlook; I enjoyed it differently.

In 2011, I started gaming under the name Rattlehead and quickly qualified for international tournaments – competing equally with other players. When my opponents learned of my visual impairment, they chalked up the win before we even began, letting their guard down. Those opponents felt tremendously surprised when I defeated them.

In that moment, a curiosity arose in my fellow gamers. They wanted to know how I did it, and their chatter made it all the way through the industry. Those early tournaments marked a turning point for blind players. The video game accessibility movement accelerated. More and more visually impaired people joined in, and the industry supported video game conferences for the blind.

Today’s technology allows blind video game champion to soar, while contributing to inclusive technologies for the visually impaired

At high level tournaments, I feel the vibration. My body shakes to the rhythm of the fans, screaming and applauding. Yet, I never focus on what I can or cannot see. I concentrate on skills – gaining respect for my ability not my blindness.

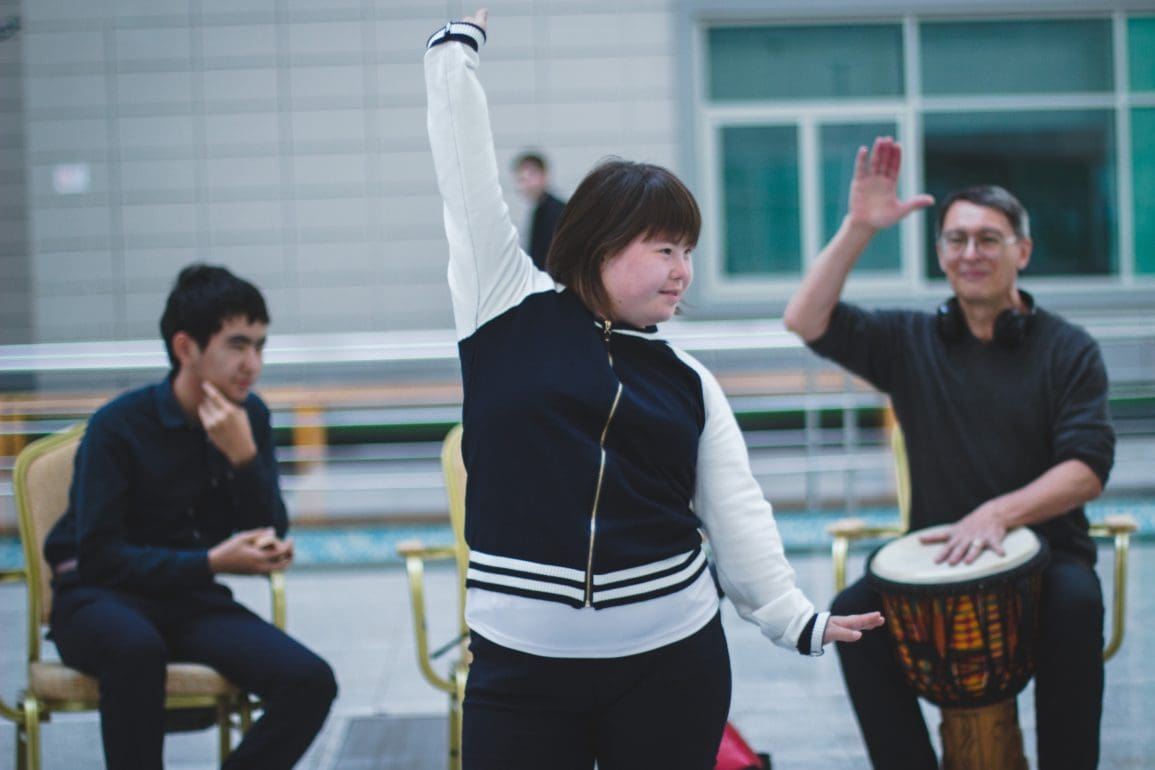

I never felt like a leader in opening the path to accessibility for blind video gamers, but I did serve as a reference for change. My motivation always remained the pleasure of play and the desire to be competitive. In the process, one by one, people entered the world of gaming because they saw me. Blind kids often approached me with surprise, saying, “I didn’t know this could be done!”

People took that inspiration, got involved in gaming, and pushed the industry forward to even higher levels. Now, with the super advanced and enriched world of audio technology, developments that positively impact blind people feel incredible to behold.

When I play a game where I am flying, I feel utterly transported. Sounds become clues, words, and guides to put my puzzle together. Though I cannot see the game, I have some reference in my memory from graphics in the ‘90s, and that is how I live.

I keep those shapes and colors in my imagination. Each time I play, it transports me to my childhood, to those video game rooms with pockets full of coins, standing on my tiptoes, dreaming of being a champion. To be actively collaborating in the development of specialized technologies for the blind today, I am part of a great future for inclusion in the video gaming industry.