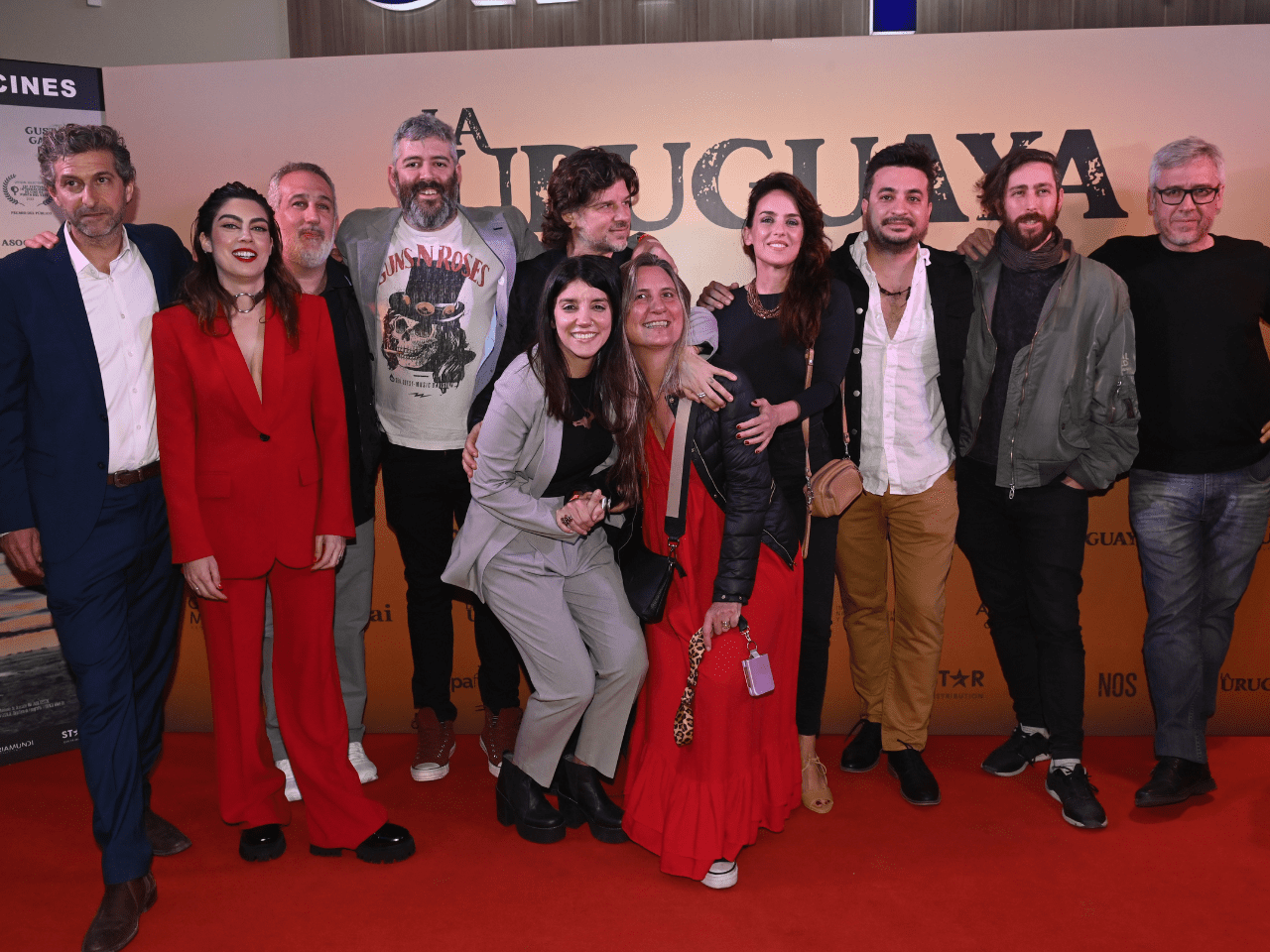

The Red Dress on tour: embroidered canvas captures the stories of vulnerable women around the world

At an exhibit in Warsaw, my excitement overflowed as I listened to refugee women from Ukraine and Poland sing traditional songs while embroidering on the dress.

- 2 years ago

May 26, 2024

LONDON, England ꟷ The Red Dress project unites the stories and cultures of artists from 28 countries in a single piece of ruby-colored silk. I started the project filled with humility and good intentions, with no idea what The Red Dress would become. I toiled for nine years, struggling to keep the project going, generate interest, obtain media coverage, and schedule exhibitions.

Today, embroiderers on the project include refugee women in Palestine and victims of civil war from Kosovo, Rwanda, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. There are improverished women from South Africa, Mexico, and Egypt, and more than 20 additional countries around the world.

Read more Art & Culture stories from around the globe at Orato World Media.

Women from around the world embroider The Red Dress in living exhibits

When I received a commission funded by the British Council to create a piece for Art Dubai 2009, I wanted to support women. I envisioned a dress made mostly by impoverished communities, offering the women a means to earn a reasonable wage while promoting their independence.

In the first version of the dress, it served as an art installation. I sat inside a fixed cube wearing the dress while embroidering it. I cut and sent panels to the embroiderers and when they finished the work, they mailed the panel back and I sewed them on. In time, I began to change the process.

Traveling around Paris, Italy, and London, I collected pieces and collaborated with so many communities and individuals. I knew the time came that I needed to completely reorganize the entire presentation of the project. From that day forward, the embroiderers worked directly on the dress. This meant they needed to be with it. We began to display The Red Dress on a mannequin at exhibitions as the embroiderers worked, giving their voice and stories center stage with no distractions.

The Red Dress tour morphed into something truly meaningful, more poetic, and increasingly collaborative. My heart called me to be more involved with vulnerable communities; to show the dress in spaces difficult to access. While I loved museums and galleries, I dreamed of taking the dress to spaces where everyone had access regardless of borders and barriers.

The best moments came when I began visiting several of the women who embroidered the dress, and I intend to visit all of them. To finally meet a woman in person who I connected with for so many years – to hug, look into eachother’s eyes, and to share stories and a cup of tea – it is magical.

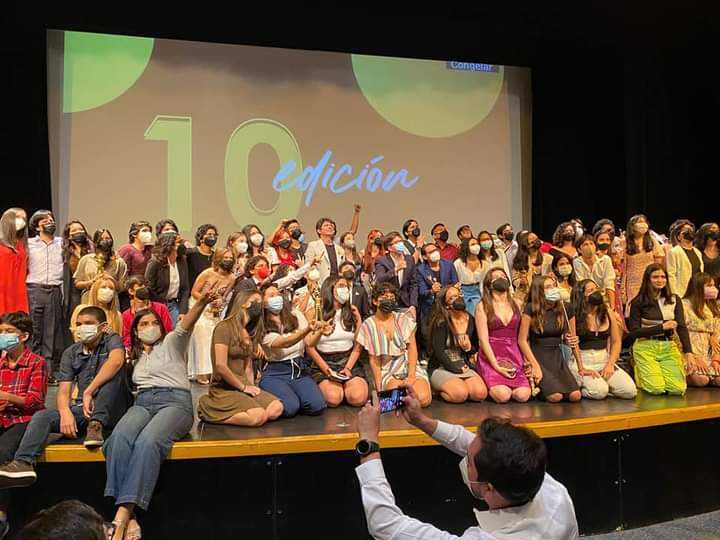

In Mexico, two women transform their communities through embroidery

In the mountains of Chiapas in Mexico, I visited emroiderers Hilaria Lopez Patishtan and Zanaida Aguilar. As we got to know one another and I visited their communities, I heard incredible stories of overcoming. At 17 years old, Hilaria began participating in The Red Dress project. Living in the Tzotzil village of San Juan Chamula, she already worked as a professional embroidery artisan. In fact, she learned at just seven years old, watching her mother’s hands work at weaving her story with colorful threads, just like their ancestors.

Zenaido saw embroidery as an opportunity to rebuild her life and help her community. After leaving an abusive relationship with her husband, Zenaida found the courage and strength in embroidery to reinvent herself. She clung to every thread and stitch, drawing a pathway toward her freedom. Today, Zenaida is not only one of the most talented embroiderers in her community, but she applies her knowledge to teach other members to embroider.

One day on that visit, at Zenaida’s house, a circle of embroiderers gathered in her kitchen. Young women from the community arrived to leave their mark on The Red Dress. Suddenly, I noticed one of the girls was the same size the dress was made in. I asked if she wanted to try it on. The girl hesitated at first, but agreed and put on the dress. When she emerged, another woman asked how she felt wearing it. “Like a queen,” she replied, “and I feel connected to all the women who worked on this dress.”

With the smell of food cooking, what was woven between the stitches that morning became a treasure I store in my heart.

Kosovo war victims create a stunning display

In Kosovo I met with sisters Feride and Fatima Halili. We exhibited the dress at the local town hall and the mayor offered a speech in the women’s honor. I watched their faces fill with happiness as tears slid down their cheeks. Seeing their reaction to the exhibit and to being honored publicly for their embroidery, I felt shocked. I finally understood what it meant to their community to contribute to this project.

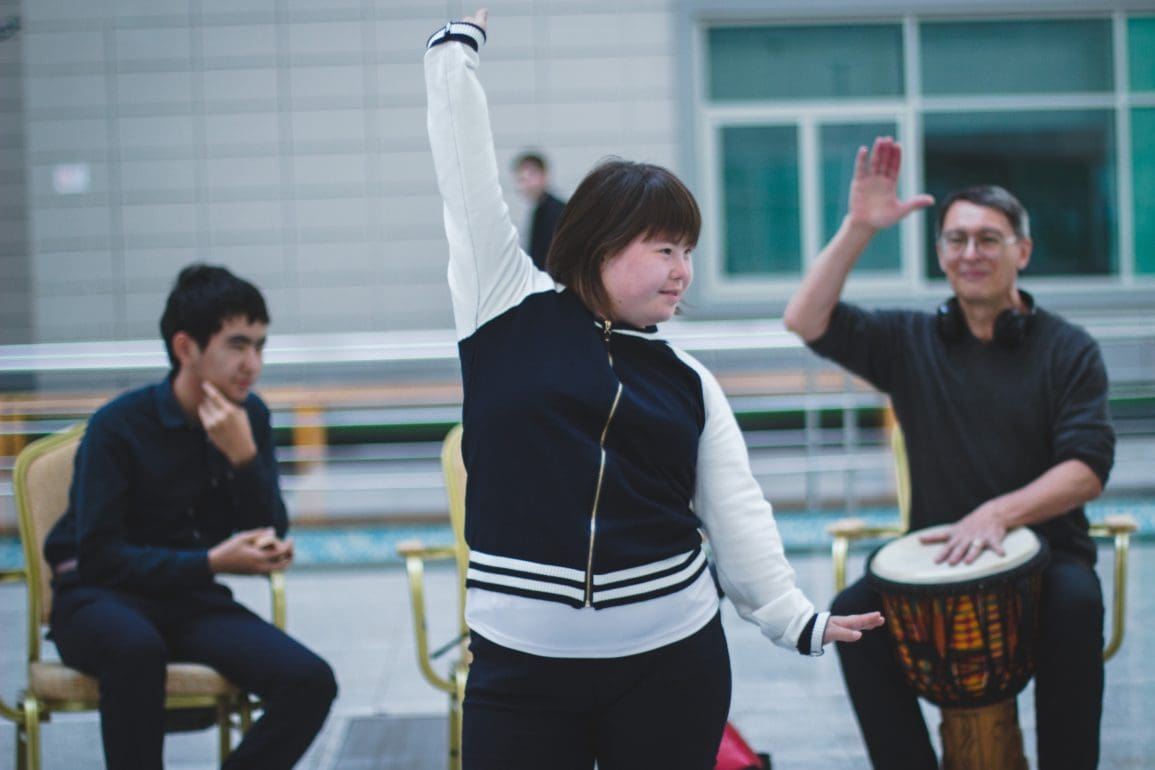

For the women in Kosovo, collective memory and art became a tool to overcome the trauma of war. Upon the dress, the two sisters embroidered birds and the words freedom and peace. The panel serves as a call to freedom. Their contribution is striking. Many incredible experiences ensued. In the Sinai desert, I joined the Fancina Bedouin community as they celebrated by performing tribal dances around The Red Dress.

At an exhibit in Warsaw, my excitement overflowed as I listened to refugee women from Ukraine and Poland sing traditional songs while embroidering on the dress. When I think of these stories it moves me to tears and quite simply, blows my mind. To walk into a room and see the dress on display creates a sense of wonder. I notice the lighting they selected and the kind of pedestal they put it on.

Each time, I fall in love with the faces of the people walking through or standing in front of the dress looking deeply entrenched in thought. Never have seen someone stand in front of it with a bored look on their face. The dress provokes joy, happiness, and enthusiasm. For many, it becomes very stimulating.

The Red Dress becomes an emblem of peace around the globe

Often, I see people crying, overwhelmed by The Red Dress. It seems as if they read every centimeter of its paper-like silk, adorned with beads. With each stitch they discover intention. In different languages, they understand the hidden message and one-by-one, the tears fall. Some hold their face in their hands, generating a unique and powerful vibration-like energy. It becomes like a sacredness to the senses.

Many messages arrive containing words of gratitude for creating the project. Some describe The Red Dress as an “emblem of peace.” The Red Dress will continue to tour the world through 2026, as I seek funds to professionally archive it, develop a book, and a feature-length documentary film. Meanwhile, I continue to conduct embroidery workshops from my studio, connecting with charities and those working towards the empowerment of women.

The dress currently remains on display at the Fuller Craft Museum in Boston, Massachusetts. It will soon return to England, South Africa, India, and back for a new show in the United States. It’s journey will take me to many faraway countries, as I go where the dress takes me. When I consider these 14 years working on The Red Dress project, it feels like a person to me; like my life’s work. I believe it is the reason I am on this earth. Every stitch of The Red Dress connects the stories of the people who sewed it.

Each bead and design adds a geographical point to its tapestry. Together, it creates a map – an overview of the lives of marginalized people in this world.

Project reflects social justice, equality, and identity

The Red Dress often feels like a fairy tale to me. From a young age I loved artistic design, sewing, and embroidery. While I could not find in words the means to express myself, I used my hands to create the visions in my imagination. I dreamed of bright, energetic, vibrant colors.

At four years old, I announced to my parents, “I am going to be artist,” and so I did. I spent hours every day drawing and soon fell in love with textiles. With a secondary passion for anthropology, The Red Dress allowed me to bring the two together.

In time, my concern about equality, social justice, and women’s rights came to the forefront. I lived my childhood in various corners of the world from Japan to Nigeria to Barbados. Being immersed in extremely different cultures – each unique and vibrant in its own way – I saw things. Everywhere I went, a commonality remained: inequality and lack of respect for women.

In time, as I grew older, I wanted to make a work that celebrated individuality and reflected different cultures and identities, but also contained the element of global collaboration. Over time, without borders, boundaries, or prejudice, through my own experiences, I created The Red Dress project. It started in my heart and captured my own identity, while portraying the essence of women throughout the world.